Searching for pictures of breast cancer lumps is usually a midnight activity fueled by pure anxiety. You find a bump. You panic. You grab your phone and start scrolling through medical diagrams and grainy clinical photos, trying to see if that thing on your screen looks like the thing on your body. Honestly, it’s a terrifying rabbit hole. But here is the thing: a photo can’t feel the density of your tissue, and it certainly can't tell the difference between a harmless cyst and something that needs an oncologist's immediate attention.

Breast cancer isn't one-size-fits-all. It’s sneaky.

Most people expect a lump to look like a distinct, angry ball under the skin. Sometimes it does. But often, the "lump" isn't even visible to the naked eye. In fact, by the time a tumor is large enough to be seen in a standard photograph, it has usually been growing for quite a while. We need to talk about what those images actually show—and what they conveniently leave out.

What You’re Actually Seeing in Pictures of Breast Cancer Lumps

When you look at medical archives or educational sites like the American Cancer Society or Mayo Clinic, the images usually fall into two categories. You have the external shots showing skin changes, and then you have the internal imaging like mammograms or ultrasounds.

If you see a photo of a breast that has a visible protrusion, you’re looking at a physical mass that is displacing the surrounding tissue. This often looks like a firm, fixed mound. It doesn't usually move when you push it. That’s a key distinction. A lot of benign lumps—think fibroadenomas—sorta slip and slide under the fingers like a marble. Cancerous lumps tend to be "tethered." They are rooted.

The "Orange Peel" and Other Visual Cues

Sometimes, the most telling pictures of breast cancer lumps aren't of the lump itself, but the skin over it. You might have heard of peau d’orange. It’s a French term that basically means the skin looks like an orange peel. It gets pitted and dimpled because the cancer cells are blocking the lymph vessels in the skin.

- Look for redness that doesn't go away.

- Check for a nipple that suddenly decided to turn inward (inversion).

- Notice any persistent scaling or crusting, especially around the areola.

Dr. Susan Love, a renowned breast cancer surgeon and author, often emphasized that the "lump" is just one piece of the puzzle. Sometimes the "lump" feels more like a thickened ridge or a "different" patch of tissue rather than a distinct grape-sized object.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

Why Your Search Results Might Be Misleading You

Google Images is a blessing and a curse. If you search for these images, you’re going to see extreme cases. Why? Because medical textbooks use extreme cases to illustrate a point. You’ll see large, ulcerated masses or severe discoloration. This can give you a false sense of security if your own "bump" looks small or "normal."

Early-stage breast cancer rarely looks like much of anything on the outside.

I’ve talked to women who found a tiny, pea-sized knot that never would have shown up in a selfie. They only found it through a self-exam or a routine mammogram. Then there’s Inflammatory Breast Cancer (IBC). This one is a real jerk. IBC often doesn't even form a distinct lump. Instead, the breast gets swollen, red, and warm. If you’re looking for a lump in pictures of IBC, you won't find one, yet it’s an aggressive form of the disease.

The Role of Density

Your breast composition matters a lot. If you have dense breast tissue (which is super common in younger women), a lump might be "camouflaged" by the surrounding glandular tissue. On a mammogram, both dense tissue and tumors show up as white. It’s like trying to find a polar bear in a snowstorm. This is why doctors often move to ultrasounds or MRIs, which can "see" through the density better than a standard X-ray.

Real Examples of What to Watch For

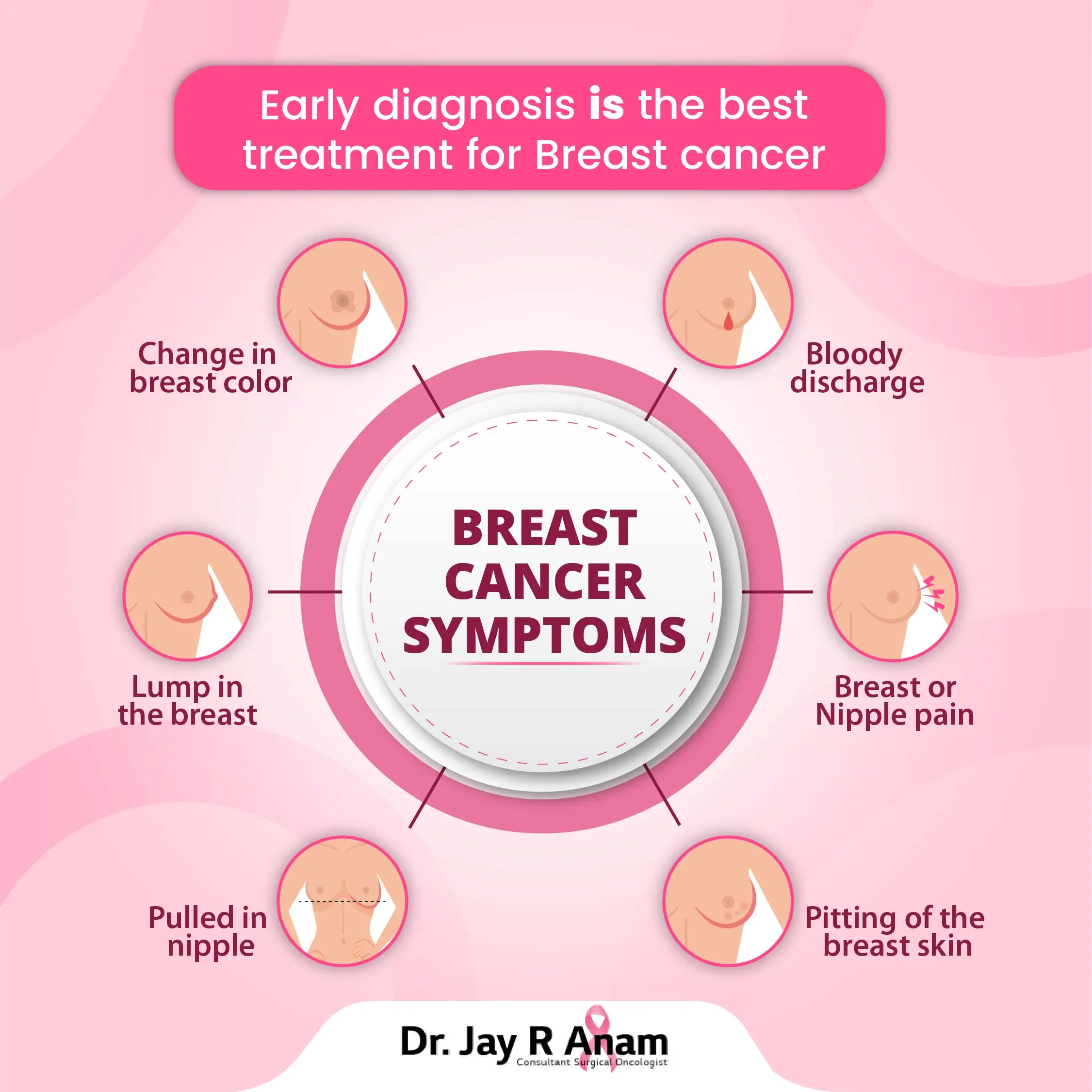

Let’s get specific. If you’re looking at your chest in the mirror, here is the checklist that actually matters, beyond just "is there a bump?"

- Asymmetry: Has one breast changed shape or size recently? Most people aren't perfectly symmetrical, but new changes are the red flag.

- Skin Dimpling: If you lift your arms above your head, does the skin pull in anywhere? This is often called a "reproducible dimple." It happens when a tumor is pulling on the Cooper’s ligaments (the connective tissue).

- Nipple Discharge: Unless you’re pregnant or breastfeeding, fluid leaking from the nipple—especially if it’s bloody or only coming from one side—needs a checkup.

- Persistent Pain: While most breast cancers are painless, a localized "heavy" feeling or a persistent ache in one specific spot shouldn't be ignored.

Dr. Kristi Funk, a breast cancer surgeon who treated Angelina Jolie, points out that while 80% of lumps end up being benign, you can't know which 80% you fall into without a biopsy or imaging. You just can't. No matter how many pictures of breast cancer lumps you compare yours to, a JPEG isn't a diagnosis.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

The Limitation of Self-Diagnosis via Images

Honestly, the internet has made us all a bit too confident in our ability to self-diagnose. We see a photo of a cyst and think, "Oh, mine looks just like that, I’m fine." Or we see a photo of a Stage IV tumor and think, "Mine doesn't look that bad, so it must be nothing."

Both thoughts are dangerous.

Cysts are fluid-filled sacs. They usually feel squishy, like a water balloon. They can hurt, especially right before your period. Cancerous lumps are typically hard—think the texture of a knuckle or a raw baby carrot. But here’s the kicker: some cancers can feel soft, and some benign things can feel rock hard.

There is also the "shadowing" effect. In an ultrasound image (one of the common types of pictures of breast cancer lumps you'll see), a malignant tumor often casts a dark shadow behind it because the sound waves can't pass through the dense mass. A cyst, being fluid, lets the sound waves through, often appearing as a clear black circle.

What Happens After You Find Something?

If you’ve found a lump and you’re currently staring at your screen comparing it to images, stop. Take a breath. Your next steps are actually pretty straightforward, even if they feel overwhelming.

First, see a primary care doctor or a gynecologist. They will do a clinical breast exam. They do this all day, every day. They know the difference between "normal lumpy" (fibrocystic changes) and "concerning lumpy."

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

From there, you’ll likely get a diagnostic mammogram. This is different from a screening mammogram. It’s more detailed. They take more pictures of the specific area of concern. If that’s still unclear, an ultrasound is next. The ultrasound uses sound waves to see if the lump is solid or liquid.

If it’s solid? They might do a fine-needle aspiration or a core needle biopsy. This sounds scary, but it’s the only way to get a definitive answer. They take a tiny sample of the cells and look at them under a microscope. That is the "gold standard." Not a Google search.

Navigating the Emotional Fallout

Finding a lump is a trauma in itself. Your brain goes to the worst-case scenario immediately. It’s human nature. But remember that "breast cancer" is a massive umbrella term. It includes everything from DCIS (Stage 0, non-invasive) to more aggressive types.

The survival rates for breast cancer caught in the early stages are incredibly high—often above 90% for a 5-year outlook. This is why we obsess over early detection.

But please, stop trying to be your own radiologist. You can find pictures of breast cancer lumps that look exactly like a harmless bruise and vice versa. The visual data is just too unreliable for the layperson.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Health

If you have found a physical change in your breast, do not wait for your annual "well-woman" exam. Do not wait for it to "go away" after your next period.

- Book an appointment today. Even if you think it's just a cyst. If it is a cyst, the doctor can drain it, and the pain goes away instantly. If it’s not, you’ve saved yourself precious time.

- Track the lump. Does it change throughout your cycle? Is it getting bigger? Write it down so you can give your doctor a clear history.

- Check your family history. While only about 5-10% of breast cancers are hereditary (BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations), knowing your history helps your doctor decide how aggressively to screen you.

- Get a Second Opinion. If a doctor tells you "you're too young for cancer" without doing an ultrasound or mammogram, find a new doctor. Age is a factor, but it's not a shield.

Ultimately, looking at photos is a starting point for awareness, not a destination for diagnosis. Your body is yours to protect. If something feels "off"—even if it doesn't look like the scary pictures you found online—trust that instinct and get it checked by a professional who has the tools to see what’s actually happening beneath the skin.

Information is power, but only when it leads to action. Take the phone out of your hand and put it to your ear to make that appointment. It’s the most important thing you’ll do all week.