You’re out there. The mud is thick, the air is crisp, and suddenly you see it—a deep, four-toed impression pressed into the riverbank. You pull out your phone, snap a few pictures of animal tracks, and head home thinking you've found a mountain lion. Then you post it in a tracking group, and some guy named Dave tells you it’s just a big golden retriever. It’s frustrating. Honestly, it’s humbling. Tracking is a language, and most of us are barely past the "ABC" stage because we rely on flat, two-dimensional images that lie to us.

The dirt tells a story, but it’s a story told in shadows and pressure. Most people think they just need a clear photo to identify an animal. They're wrong. A photo without context is just a shape, and shapes in nature are notoriously fickle.

The Problem With Your Pictures of Animal Tracks

Let's be real: your phone camera is actually working against you. Most smartphone sensors are designed to flatten images and smooth out "noise." In the world of tracking, that "noise" is actually the minute detail—the grit of a claw mark or the slight "register" where a hind foot stepped exactly into the print of a front foot. When you take pictures of animal tracks from a standing position, you lose the depth.

Depth is everything.

Professional trackers like Mark Elbroch, author of the definitive Mammal Tracks & Sign, talk about "grounding" the track. If you don't have a scale in the shot, your photo is basically useless. Is that a wolf or a coyote? Without a ruler or a standard-sized object like a quarters or a credit card, the camera lens can make a tiny fox print look like a monster. And please, for the love of all things holy, stop using your hand as a scale unless you want everyone to know exactly how small your gloves are.

It's also about the light. High noon is the absolute worst time to photograph a track. The sun is directly overhead, washing out the shadows that define the edges of the toes and the heel pad. You want "side-lighting." Think of it like theater lighting; you need the shadows to fall into the deep parts of the track to show the "wall" and the "floor" of the impression. If the sun isn't cooperating, trackers use a trick: they use their own body to shade the track and then use a small flashlight held at a low angle to create artificial shadows.

Why Every "Wolf" Is Usually a Dog

I’ve seen it a thousand times. Someone posts a photo of a massive, clawed print and swears they’ve found a timber wolf in the middle of suburban Ohio. It’s almost always a dog. Dogs and wolves are genetically close, sure, but their "track signatures" are different. A domestic dog has a messy walk. They’re pampered; they don’t care about saving energy, so they trot around, their toes splayed out, and their hind feet rarely land in the same spot as their front feet.

👉 See also: Sleeping With Your Neighbor: Why It Is More Complicated Than You Think

Wild canines are different. A coyote or a wolf is an athlete. They move with "direct register" to conserve energy, especially in snow or deep mud. This means their back foot lands almost perfectly in the hole left by the front foot. When you look at pictures of animal tracks from a wolf, you’ll see a narrow, purposeful line of prints. A dog’s trail looks like a drunken stumble in comparison.

Also, look at the "X." If you can draw a clean "X" through the negative space between the toes and the heel pad without hitting any meat, you’re likely looking at a canine. If the "X" is blocked by a large, bulbous heel pad, you might be looking at a feline. But even that isn't a hard rule. Mud spreads. Ice melts. A small track can "grow" as the sun warms the ground around it, turning a house cat into a bobcat in a matter of hours.

Reading the Substrate: Why Mud Lies

The ground itself is a liar. We call the surface "the substrate," and it dictates how a track looks more than the animal's foot does.

Imagine a 150-pound deer jumping over a log into soft silt. The impact is going to blow out the track, making it look twice as big as it actually is. Now imagine that same deer walking across sun-baked clay. It might only leave a tiny, faint clip of its hoof. If you only look at pictures of animal tracks without considering the soil type, you're going to get it wrong.

Expert trackers look for "ejecta"—the dirt that gets kicked out of the track. If the dirt is still damp and dark, the track is fresh. If the edges are crumbly and dry, it’s old news. This is the stuff a camera usually misses unless you’re getting down in the dirt, literally. You have to get your nose near the ground. You have to smell the earth.

- Wet Silt: Captures every detail, including the fine "frixion ridges" on a raccoon's paw.

- Dry Sand: Basically the worst. It’s like trying to draw in sugar. Everything collapses into a generic "pit."

- Snow: Complicated. A track in fresh powder is just a hole. A track in "corn snow" (melting and refreezing) can magnify a squirrel track into something that looks like it belongs in Jurassic Park.

The Feline vs. Canine Debate

This is the classic argument. People see claws and think "dog." They don't see claws and think "cat." While it's true that cats have retractable claws, they don't always keep them tucked in. If a mountain lion is slipping on a muddy slope, it’s going to dig those claws in for traction. Suddenly, your "cat" track has claw marks.

✨ Don't miss: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The real giveaway is the heel pad. Canines have a heel pad with one lobe on the top and two on the bottom. Felines have two lobes on the top and three on the bottom. It looks like a little "M" or a trapezoid. If you're taking pictures of animal tracks to prove a cougar sighting, you need to clear the debris out of that heel pad area carefully. Use a blade of grass or a soft breath of air. Don't use your finger, or you'll smudge the very evidence you're trying to capture.

The Art of the Trackway

A single track is a data point. A "trackway" is a story.

When you find a set of prints, don't just photograph one. Walk alongside them. Take a wide-angle shot of the whole path. This shows the "stride" (the distance between two prints of the same foot) and the "straddle" (the width of the walk). A wide straddle usually means a heavy-bodied animal like a badger or a bear. A narrow straddle suggests a fast, efficient traveler like a fox.

I remember finding a set of tracks in the Cascades that looked like a person walking on their hands. It was bizarre. Only by following the trackway for twenty yards did I realize it was a porcupine. They have this waddling, heavy-tailed gait that drags through the snow, obscuring the actual foot impressions. Without the context of the whole trail, I would have been completely lost.

Identifying the Weird Stuff

Sometimes you find things that don't make sense. Raccoons are the biggest culprits. Their front paws look like tiny human hands, which is creepy enough at night, but their gait is a "pacer" gait. They move both limbs on one side of the body at the same time. This results in pictures of animal tracks where a "hand" is sitting right next to a "foot."

And then there are the "jumpers" and "bounders."

🔗 Read more: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

- Mice and Squirrels: They usually land with their larger hind feet in front of their smaller front feet. It looks backward.

- Weasels and Otters: They "bound," meaning their bodies stretch and compress. Their tracks often appear in pairs or sets of four that look like a jumbled mess.

If you find a track that looks like a miniature human hand with a thumb, it's an opossum. Their "thumb" (hallux) is opposable and sticks out at a nearly 90-degree angle. It's one of the easiest tracks to identify, yet people still freak out when they see it on their back porch mud mat.

Practical Advice for Better Wildlife Documentation

If you actually want to get good at this, you need to change how you move through the woods. Most people walk "heavy." They look at their feet. Stop. Look ten feet ahead. Look for the "shimmer" in the grass where the blades have been bent. Tracking isn't just about holes in the dirt; it's about "sign."

When you take pictures of animal tracks, follow this checklist:

- Place a ruler next to the track. If you don't have one, use a dollar bill (exactly 6.14 inches) or a standard coin.

- Get low. Your camera should be at a 45-degree angle to the track, not pointing straight down.

- Take a "context shot." Show the environment. Is it near water? Is there scat nearby?

- Check the gait. Measure the distance between the prints with your phone's "measure" app if you have to.

There is a real sense of connection that comes with this. When you realize that the "dog" track in your yard is actually a red fox that passes through every Tuesday at 3:00 AM, the world feels a little bigger. You aren't just looking at dirt anymore; you're reading the morning newspaper of the forest.

Actionable Next Steps for Aspiring Trackers

To move beyond being a casual observer and start identifying tracks like a pro, start with these specific actions:

- Create a "Tracking Kit": Keep a small 6-inch transparent ruler and a high-lumen flashlight in your pack. The ruler provides scale, and the flashlight allows you to create "false dusk" shadows even in the middle of the day.

- Use the iNaturalist App: Don't just save photos to your camera roll. Upload your pictures of animal tracks to iNaturalist. The AI is decent, but the real value is the community of expert naturalists who will verify your find and provide feedback on why you're right or wrong.

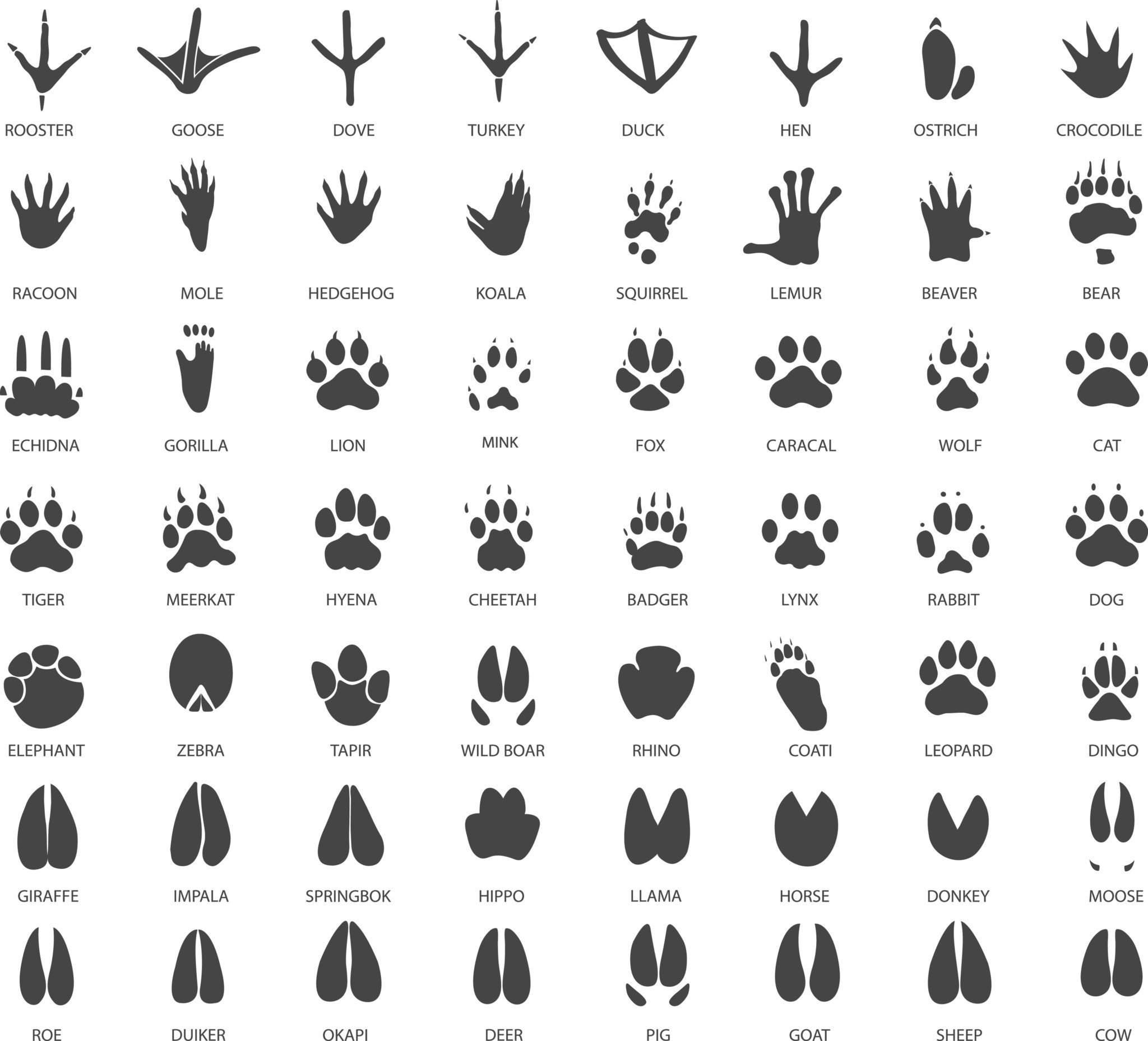

- Study "The Big Three": Focus on mastering the difference between Canid (dog/wolf/fox), Felid (cat/cougar/bobcat), and Mustelid (weasel/otter/marten) track patterns. Once you know the "family" shape, narrowing down the species becomes much easier.

- Practice "Backtracking": When you find a fresh track, follow it backward. This is often easier than following it forward because you can see where the animal came from without worrying about stepping on the "fresh" sign. It teaches you about their behavior—where they rest, where they drink, and where they hunt.

- Document the Scat: It’s gross, but it’s vital. Animal tracks tell you who was there; scat tells you what they were doing. If the track is ambiguous, looking for nearby droppings can confirm the species based on the presence of fur, berries, or bone fragments.