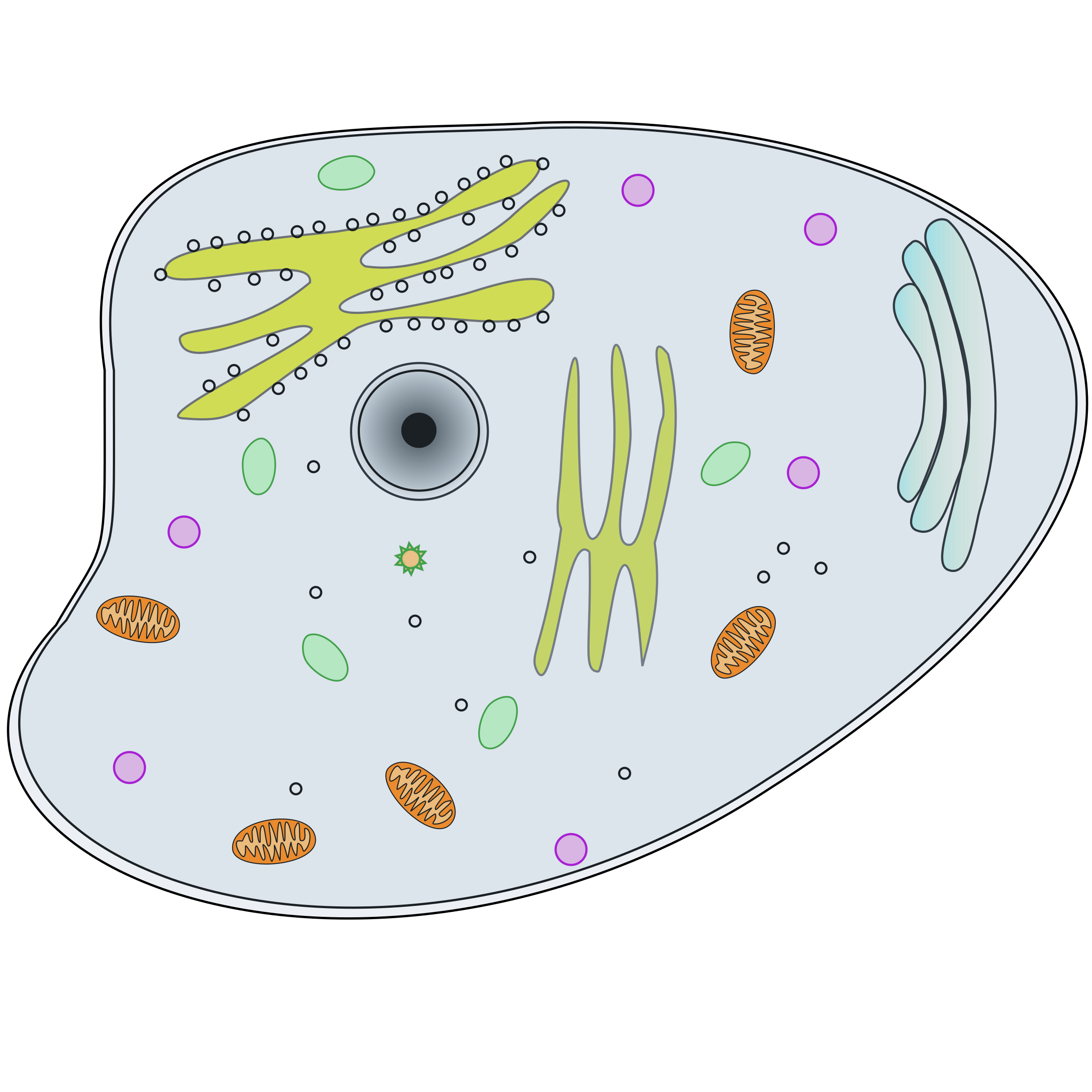

You’ve seen them a thousand times. Those neon-colored, gelatinous blobs in biology textbooks that look more like a 1960s lava lamp than a living building block. Honestly, most pictures of animal cell structures are kind of a lie. They’re stylized. They’re simplified. They’re designed to make sure you don't fail a freshman bio quiz, but they often miss the chaotic, crowded reality of what’s actually happening inside you right now.

Cells are packed.

If you could actually shrink down and look at a human cheek cell or a neuron without the artificial dyes, you wouldn't see a neat purple nucleus sitting in a clear pool of water. You'd see a high-traffic metropolitan area during rush hour. Everything is moving. Proteins are tumbling, membranes are folding, and the "empty space" is actually a thick, protein-rich soup called the cytosol.

The Problem With Typical Pictures of Animal Cell Diagrams

We have to talk about the "Fried Egg" model. It’s the classic view: a circle with a dot in the middle. While this helps beginners identify the nucleus, it fails to capture the three-dimensional complexity that modern imaging technology, like Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM), has recently revealed.

Take the work of Dr. David Goodsell, a structural biologist at the Scripps Research Institute. His paintings and digital renderings are widely considered some of the most accurate pictures of animal cell environments ever created. Instead of vast open spaces, Goodsell shows a world where molecules are literally bumping into each other. There isn't room to breathe. When you look at his work, you realize that the traditional textbook diagram is basically a map of the New York City subway that forgets to include the buildings, the people, and the concrete.

Why the Colors are Usually Fake

Here’s a secret: cells are mostly transparent. When scientists use a light microscope to take pictures of animal cell samples, they usually have to use stains like Methylene Blue or Eosin. Without these, the cell would look like a faint, watery ghost. The vibrant pinks and greens you see in National Geographic aren't "real" in a literal sense. They are "false-color" images created by fluorescent tagging.

✨ Don't miss: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

By attaching a glowing protein—often the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) discovered in jellyfish—to a specific part of the cell, researchers can make the mitochondria glow lime green while the DNA glows bright red. It’s beautiful. It’s also a tool. It allows us to see how a virus invades a nucleus in real-time. But don't go thinking your internal organs are a neon rave.

Understanding the Organelle "Traffic"

When you’re scrolling through high-resolution pictures of animal cell internals, the Mitochondria usually stand out. They look like little beans with squiggly lines inside. Everyone knows the "powerhouse" meme, but the visual reality is more interesting. Mitochondria aren't static beans. They are constantly fusing together into long networks and breaking apart again. They move like lava.

Then you have the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER). In most 2D pictures of animal cell anatomy, the ER looks like a stack of pancakes near the nucleus. In reality, it’s a massive, winding labyrinth that makes up more than half of the total membrane in the cell. It’s the factory floor. If you're looking at a cell from the liver, that ER is going to look way more rugged and expansive than it would in, say, a skin cell, because the liver is a chemical processing plant.

The Cytoskeleton: The Invisible Scaffolding

One thing almost every basic picture gets wrong is the "emptiness" of the cytoplasm.

Imagine a house. The textbook diagram shows the furniture (organelles) floating in mid-air. Real life shows the studs in the walls, the floor joists, and the rafters. That’s the cytoskeleton. It’s a dense forest of microtubules and filaments.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

- Microtubules act like train tracks for transport proteins.

- Actin filaments give the cell its actual shape, pushing against the membrane.

- Intermediate filaments act like anchors, making sure the nucleus doesn't just drift off to the corner of the cell when you go for a jog.

Modern Imaging: Beyond the Optical Limit

The most mind-blowing pictures of animal cell structures today don't even use light. They use electrons. Because the wavelength of visible light is too "fat" to see the tiny details of a ribosome, we use Electron Microscopy (EM).

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) gives us those "3D" looking shots where a white blood cell looks like a fuzzy tennis ball. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) goes through the cell, showing us the razor-sharp edges of the Golgi apparatus.

Recently, a technique called "Expansion Microscopy" has changed the game. Scientists literally bake the cell into a gel that swells up when water is added, physically enlarging the cell to 40 times its size. This allows us to take pictures of animal cell components using regular microscopes that would normally require multi-million dollar equipment. It’s like blowing up a balloon with a drawing on it so you can see the pencil marks better.

What to Look for in a "Good" Scientific Image

If you're a student or a creator looking for the best pictures of animal cell references, stop looking at clip art. Clip art is the death of nuance.

- Look for Scale Bars: A real scientific image will always tell you how big the object is (usually in micrometers, $\mu m$). If there's no scale bar, it's probably an illustration, not a photograph.

- Check the Source: Reliable images come from databases like the Cell Image Library or the Protein Data Bank.

- Search for "In Situ": If you want to see how cells actually look inside a tissue, search for "histology" or "in situ" images. These show cells packed together like tiles, rather than floating in a void.

The cell membrane isn't just a bag. It’s a "fluid mosaic." It’s a sea of lipids with protein "icebergs" floating in it. When you look at pictures of animal cell boundaries, try to find ones that show the carbohydrate chains sticking out of the top—they look like tiny antennae. These are what your immune system uses to "scan" the cell to see if it belongs there or if it's an intruder.

💡 You might also like: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

Practical Steps for Visual Learners

To truly grasp the architecture of life, don't just stare at one diagram. Compare.

Find a picture of a neuron (long, spindly, electric) and compare it to a muscle cell (long, striped, packed with mitochondria). The visual differences tell you everything about what those cells do for a living. Form follows function. A neuron needs to send signals over long distances, so it looks like a wire. A muscle cell needs to contract, so it looks like a bundle of ropes.

If you are trying to learn this for a class, try drawing a cell without using a circle. Draw it as a square, a star, or a blob. Once you break the "circle-and-dot" habit, you start seeing the cell as a dynamic machine rather than a static map.

Go to the NASA GeneLab or the Allen Institute for Cell Science. They have open-source, high-quality 3D visualizers that let you rotate a real human cell and toggle different parts on and off. It's the closest thing we have to a "Google Earth" for the microscopic world. Seeing the spatial relationship between the Golgi and the ER in 360 degrees will teach you more in five minutes than a flat textbook page will in an hour.

Actionable Insight: When studying or sourcing pictures of animal cell layouts, prioritize "Fluorescence Micrographs" over "Illustrations." Micrographs show you the actual biological data—the messy, beautiful reality of life—while illustrations often oversimplify the crowded nature of the cytoplasm. To see the most cutting-edge visuals, search for "4D cell imaging" to witness how these structures move over time, rather than just seeing a frozen snapshot.