You’ve seen them a thousand times. Those glossy, neon-colored pictures of anatomy of human body in your doctor's office or splashed across the pages of a high school biology textbook. They make everything look so tidy. The veins are a crisp, royal blue. The arteries are fire-engine red. The nerves look like perfectly laid yellow cables, organized by a master electrician.

But honestly? Inside you, it's a mess.

It is a beautiful, wet, pulsing, crowded mess. If you actually saw a real cadaver or a high-resolution surgical photo, you’d realize that humans don't come in "textbook" colors. Everything is mostly a shade of pinkish-tan or yellowish-white, slick with fascia—that spider-web-like connective tissue that keeps your guts from sloshing around when you do a jumping jack. Most people look at anatomical illustrations and think they’re looking at a map. In reality, those images are more like a subway diagram. They show you where things go, but they don't show you the traffic, the grime, or the weird structural quirks that make your body different from mine.

The Problem with "Standard" Anatomical Illustrations

We have this obsession with the "average." Most pictures of anatomy of human body are based on a 150-pound male specimen. This isn't just a diversity issue; it’s a clinical one. If you only study those specific diagrams, you might miss the fact that some people are born with their organs flipped (situs inversus) or that about 20% of the population is missing a muscle in their forearm called the palmaris longus.

Dr. Caspar Wistar, an early American anatomist, used to spend hours just cataloging how much variation there was in the branching of the aortic arch. He knew something we often forget: no two bodies look the same on the inside.

When you look at a digital rendering of a skeleton, the bones are bleach-white and smooth. Real bones are alive. They have textures. They have "landmarks"—tiny bumps and ridges where tendons have pulled and tugged over decades of movement. If you’re a runner, the attachment points for your hamstrings on your pelvis are going to look beefier than someone who sits at a desk all day.

Standard diagrams ignore this "plasticity." They treat the human form as a static object, like a car engine. But engines don't heal, and engines don't change their shape based on how you drive them.

Why the Colors Are All Wrong

Ever wonder why veins are blue in every single picture? It’s a lie.

🔗 Read more: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

Well, a white lie.

Deoxygenated blood is actually a very dark, dusky red. It only looks blue through your skin because of how light wavelengths interact with your subcutaneous fat and dermal layers. If you were to look at an exposed vein during surgery, it would look dark purple or maroon. We use blue in pictures of anatomy of human body because it makes the diagrams easier to read. If everything were red, you couldn’t tell what was going where.

Then there’s the lymphatic system. In most books, it’s green. There is absolutely nothing green about your lymph nodes. They’re usually small, bean-shaped, and off-white. We just collectively agreed on green as a color code so it wouldn't get confused with the yellow used for nerves. It’s basically a UI/UX choice for the human body.

The New Era of 3D Imaging and "Real" Photos

We are finally moving past the era of the 2D drawing. Modern technology like the Visible Human Project, which started back in the 90s, changed everything. They took a cadaver, froze it in gelatin, and sliced it into thousands of millimeter-thin layers. They photographed every single slice.

It was gruesome.

It was also the first time we had a truly accurate, pixel-perfect map of a human. Since then, MRI and CT scans have allowed us to create 3D renders that move in real-time. You can now see a 4D ultrasound of a baby yawning in the womb, or a "cinematic rendering" of a beating heart that looks like a high-budget Marvel movie.

These high-tech pictures of anatomy of human body are incredible, but they also bring new challenges. They show so much detail that doctors sometimes find "incidentalomas"—tiny, harmless anomalies that look like problems on a high-res scan but are actually just normal human variation. Sometimes, too much detail leads to over-diagnosis.

💡 You might also like: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

Fascia: The Stuff We Used to Throw Away

For centuries, anatomists would cut through the "white fuzz" covering the muscles and toss it in the bin. They thought it was just packing material.

They were wrong.

That "fuzz" is the interstitium and the fascia. Newer photography and microscopic imaging show that this stuff is actually a massive, body-wide communication network. It’s a fluid-filled highway. If you look at a modern anatomical picture of the fascia, it looks like a complex, glistening web. This has totally changed how we think about chronic pain and how injuries in the foot can actually cause headaches. Everything is literally connected, but old-school pictures didn't show that because the illustrators would "clean up" the image to make the muscles look pretty.

Looking at Your Organs Differently

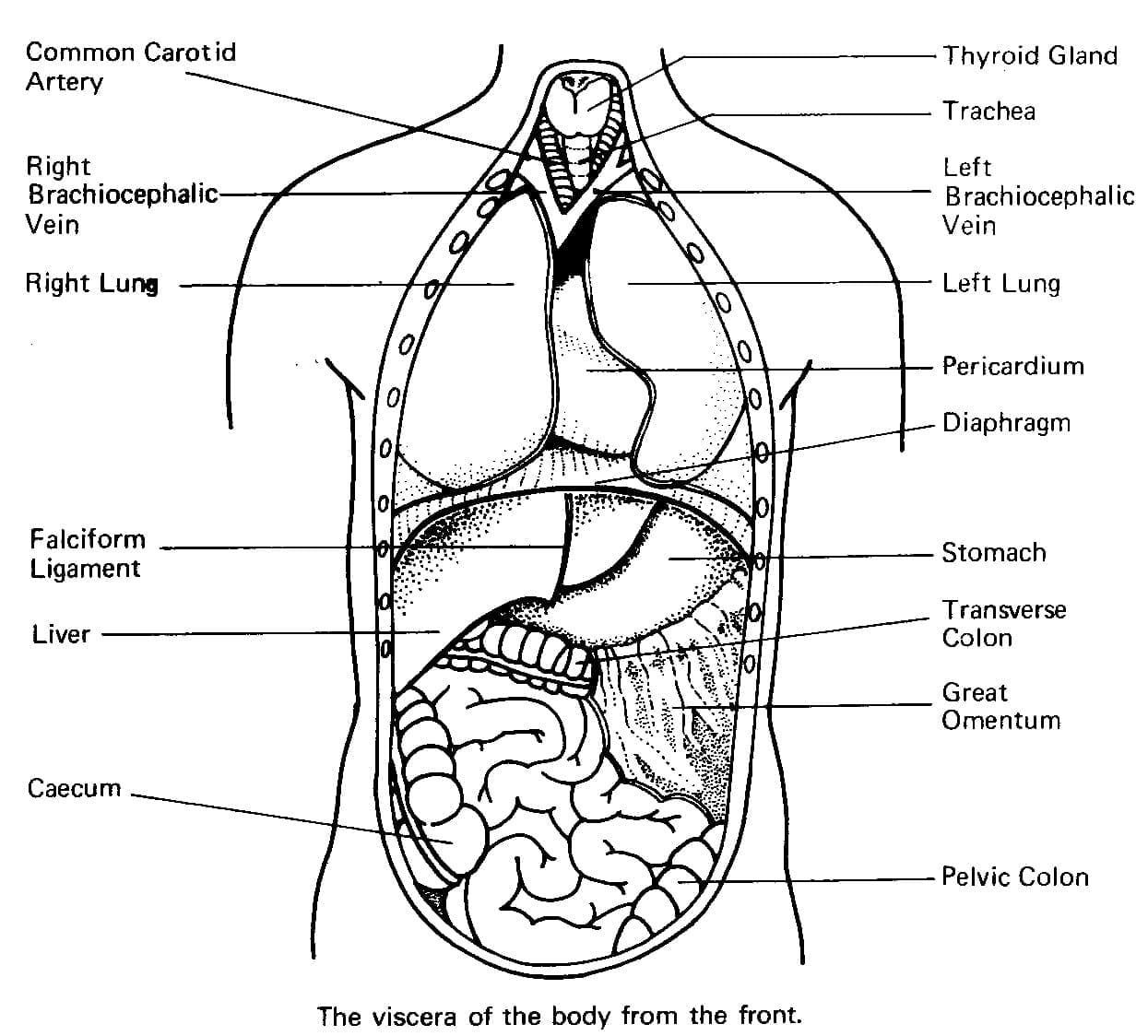

Your stomach isn't a neat little pouch in the center of your torso. It’s tucked up high, mostly on the left, hiding under your ribs. Your liver is much bigger than you think; it’s a massive, heavy organ that dominates the upper right side of your belly.

When you see pictures of anatomy of human body that show the digestive tract, they often look like a garden hose neatly coiled. In a living person, those intestines are constantly squirming. It’s called peristalsis. They shift. They move. If you lie on your left side, your organs literally settle into a different configuration than if you lie on your right.

And the brain?

The brain in pictures is usually a firm, grey-ish walnut. In reality, a fresh human brain has the consistency of soft tofu or thick pottage. It’s so fragile that it would collapse under its own weight if it weren't floating in cerebrospinal fluid. Those deep grooves (sulci) and ridges (gyri) are how your body crams a massive amount of "computing power" into a small skull.

📖 Related: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

The Hidden Diversity of the Skeleton

Even the skeleton, the most "fixed" part of our anatomy, is a bit of a shapeshifter.

- The Pelvis: Female pelves are generally wider and have a larger "outlet," but there’s a huge overlap between sexes.

- The Skull: The thickness of your cranium varies wildly based on genetics and age.

- The Teeth: X-rays are just another form of anatomical pictures, and they reveal how our modern diets have actually shrunk our jawlines compared to our ancestors.

Actionable Ways to Use Anatomical Knowledge

If you’re looking at pictures of anatomy of human body to understand a medical condition or for a fitness goal, you have to be smart about it. Don't just look at one "perfect" drawing and assume that's what you look like inside.

Compare multiple sources. Look at a traditional illustration, then look at a 3D scan, and then—if you have the stomach for it—look at a "plastination" photo from something like the Body Worlds exhibit. This gives you a sense of the depth and the "crowdedness" of your internal space.

Focus on the layers. Understand that between your skin and your bone, there are layers of fat, superficial fascia, deep fascia, and muscle. When you feel a "knot" in your shoulder, you aren't feeling the bone; you're feeling a literal tension in those soft tissue layers that usually doesn't show up on a standard X-ray.

Ask for your own images. If you ever get an MRI or a CT scan, ask for the digital files. Most hospitals will give them to you on a disc or through a portal. Seeing your own anatomy—your specific spine, your specific heart—is a thousand times more educational than looking at a generic diagram. You'll see the slight curve in your neck or the way your sinuses are shaped.

Recognize the limits of "normal." If a diagram shows a muscle you don't seem to have, or an artery that seems to branch differently on your scan, don't panic. Anatomy is a spectrum. We are all slight variations on a theme.

The next time you see a picture of the human body, remember that it's a map, not the territory. Your body is a unique, living, changing landscape that no single artist can ever fully capture. Use those pictures as a starting point, but don't let them convince you that you're supposed to be as tidy as a textbook. You aren't. And that's exactly why the human body works as well as it does.

Next Steps for Better Understanding

- Use interactive 3D apps: Tools like Complete Anatomy allow you to peel back layers yourself, which is way more intuitive than a flat page.

- Search for "cross-section" anatomy: Looking at the body from a "top-down" slice (transverse plane) helps you understand how organs actually pack together.

- Check the source: Always verify if an image is an "artistic rendering" or "medical-grade visualization." Artistic versions often prioritize aesthetics over anatomical precision.