Visuals tell a story that data just can't. When you search for pictures of AIDS and HIV, you aren't just looking for clinical diagrams of a retrovirus. You're looking for the human face of a pandemic that has defined the last forty years. It’s heavy stuff. Honestly, the imagery we associate with this virus has shifted so dramatically since the 1980s that looking at a photo from 1985 versus a photo from 2026 feels like looking at two different planets.

The early days were brutal. Think back to the grainy, black-and-white photography of activists like Therese Frare. Her 1990 photo of David Kirby on his deathbed, surrounded by his family, changed how the world saw the disease. It wasn’t just a "gay plague" anymore; it was a human tragedy. But those images also cemented a very specific, very terrifying aesthetic of what HIV looks like. Emaciated bodies. Sunken eyes. Purple lesions from Kaposi sarcoma.

These images were necessary to wake people up, but they also created a lingering stigma that we are still fighting today.

What Pictures of AIDS and HIV Actually Look Like Now

If you look at modern photography of people living with HIV, you won't see the "dying patient" trope anymore. You'll see runners, parents, and professionals.

This change isn't accidental. It's the result of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART).

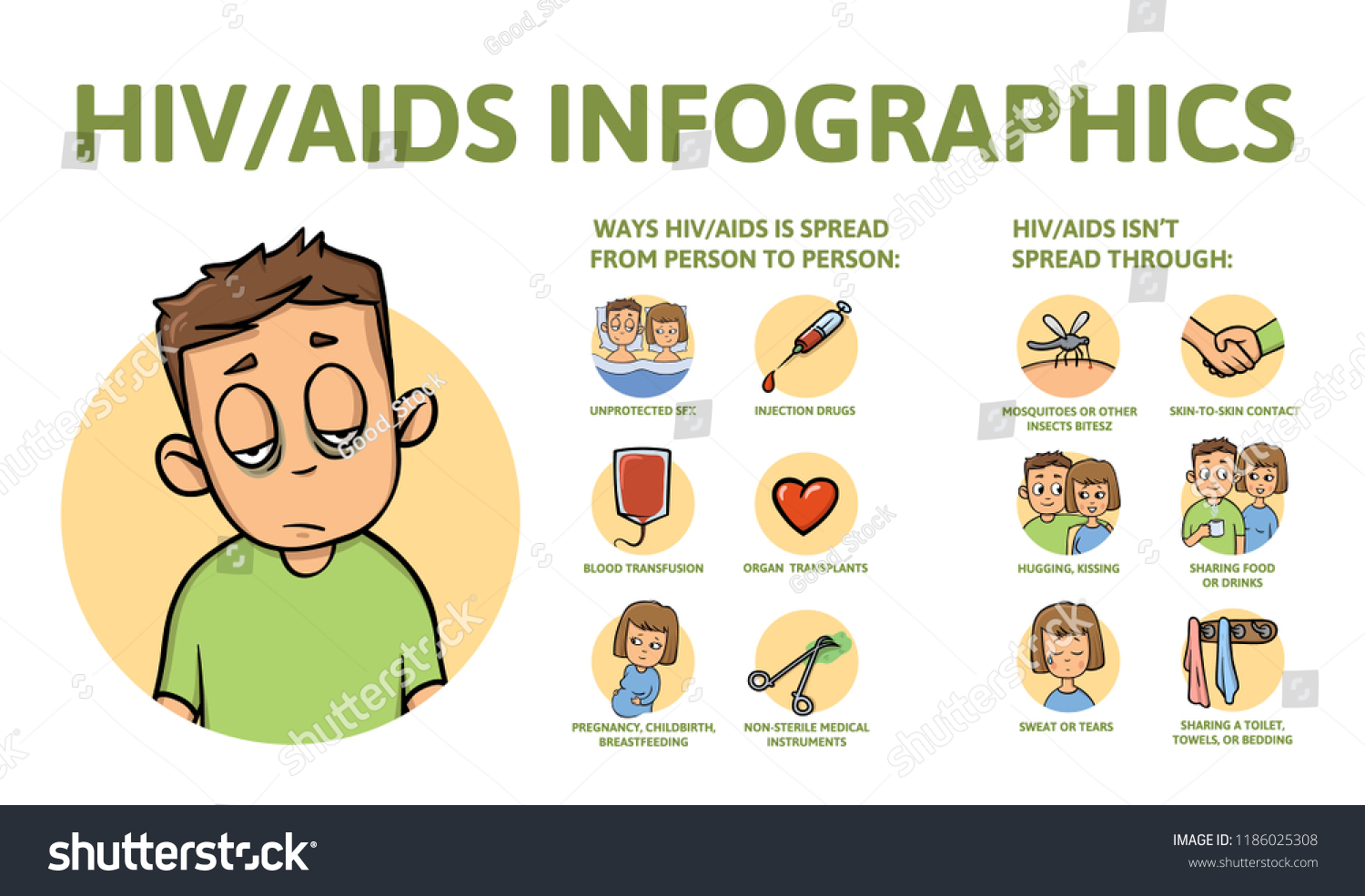

When we talk about pictures of AIDS and HIV in a medical context today, we are often looking at microscopic renderings or infographics about viral loads. The actual "look" of a person with HIV in 2026 is, well, totally normal. If someone is adherent to their medication, they reach a state called "Undetectable," meaning the virus is so low in their blood that it can't be passed on to partners. U=U. Undetectable equals Untransmittable. That is a massive shift in the visual narrative.

The Microscopic Reality

Under an electron microscope, HIV is actually quite "beautiful" in a terrifying way. It’s a spherical structure, roughly 100 nanometers in diameter. It’s covered in spikes made of proteins—specifically gp120 and gp41—which it uses to latch onto CD4 cells.

💡 You might also like: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

If you're looking at clinical pictures of AIDS and HIV, you're seeing the virus budding from a host cell. It looks like tiny bubbles emerging from the surface of a much larger sphere. Once it breaks free, it matures and goes on to infect the next cell. This cycle is what doctors spend their lives trying to break.

Skin Manifestations: Myths vs. Reality

People often search for photos because they have a rash and they're spiraling. They see a red bump and think, Is this it? Let's be real: most "HIV rashes" are incredibly non-specific. During the acute infection stage (the first few weeks), some people get a maculopapular rash. It looks like small, flat, red bumps. It’s often mistaken for the flu or a drug reaction.

- Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is the one people recognize from old movies. These are dark purple or brown lesions.

- Because of modern meds, KS is much rarer in the U.S. than it used to be.

- Oral thrush (white patches in the mouth) is another common visual cue, but it can happen to anyone with a weakened immune system, not just those with HIV.

- Shingles can also be an early visual warning sign if it appears in someone young and otherwise healthy.

The Evolution of the Red Ribbon

Visuals aren't just about the body. The red ribbon is probably the most famous piece of "HIV imagery" in history. Created in 1991 by the Visual AIDS Artists' Caucus, it was designed to be easy to copy. No copyright. No branding. Just a loop of ribbon pinned to a lapel.

It was a visual scream. It said, "We are here, and we are dying."

Today, the ribbon is still around, but it’s joined by more vibrant, hopeful imagery. Digital campaigns now focus on "Ending the Epidemic" by 2030. The visual language has moved from mourning to management.

Why the "Face of AIDS" is Diverse

For a long time, the media only showed one type of person in pictures of AIDS and HIV. Usually white, usually male, usually emaciated. That was a huge mistake.

📖 Related: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

The reality of the epidemic globally is far more complex. In Sub-Saharan Africa, women and girls account for a huge percentage of new infections. In the U.S., the epidemic disproportionately affects Black and Latino communities, particularly in the South.

When you look at modern photojournalism projects, like those by the Elton John AIDS Foundation or UNAIDS, you see a global mosaic. You see grandmothers in South Africa raising orphans. You see trans women in Thailand accessing PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis). You see the resilience of the human spirit.

Understanding the Difference Between HIV and AIDS

It sounds basic, but many people still use the terms interchangeably. They shouldn't.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is the virus. AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) is the late stage of infection.

Technically, you can't "see" AIDS on a person just by looking at them anymore. A person has an AIDS diagnosis when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/mm3 or when they develop a specific opportunistic infection. With modern treatment, many people who once had an AIDS diagnosis actually recover their immune systems to the point where they technically only have "HIV" again.

That’s a miracle of science.

👉 See also: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

The Role of PrEP and PEP in Modern Visuals

There’s a new kind of "HIV picture" trending: the blue pill.

PrEP, or Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, has changed the game for HIV prevention. The visual of a single daily pill has become a symbol of sexual freedom and safety. Then there's PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis), which is the "morning-after pill" for HIV exposure.

These aren't just medications; they are visual markers of a world where HIV is preventable. If you've been exposed, you have 72 hours to start PEP. The sooner, the better.

Actionable Steps for Health Management

Searching for pictures of AIDS and HIV usually stems from one of two things: curiosity about history or personal anxiety about a possible exposure. If it’s the latter, stop looking at pictures. Photos on the internet cannot diagnose you.

- Get Tested: This is the only way to know. Modern 4th generation tests can detect HIV as early as 18 to 45 days after exposure. Some rapid tests are available at pharmacies for home use.

- Talk to a Doc About PrEP: If you are sexually active and want to stay negative, PrEP is 99% effective when taken as prescribed.

- Check for PEP: If you think you were exposed in the last 72 hours, go to an ER or urgent care immediately. Don't wait for a rash to appear.

- Look Past the Stigma: If you or someone you know tests positive, remember that it is no longer a death sentence. People on effective treatment live full, long lives.

- Use Reliable Sources: Stick to the CDC, Mayo Clinic, or the World Health Organization (WHO) for clinical images. Avoid "shock" sites that use outdated photos to scare people.

The visual history of this virus is a roadmap of human struggle and scientific triumph. We’ve gone from photos of hospital beds to photos of marathons. That is progress you can actually see.