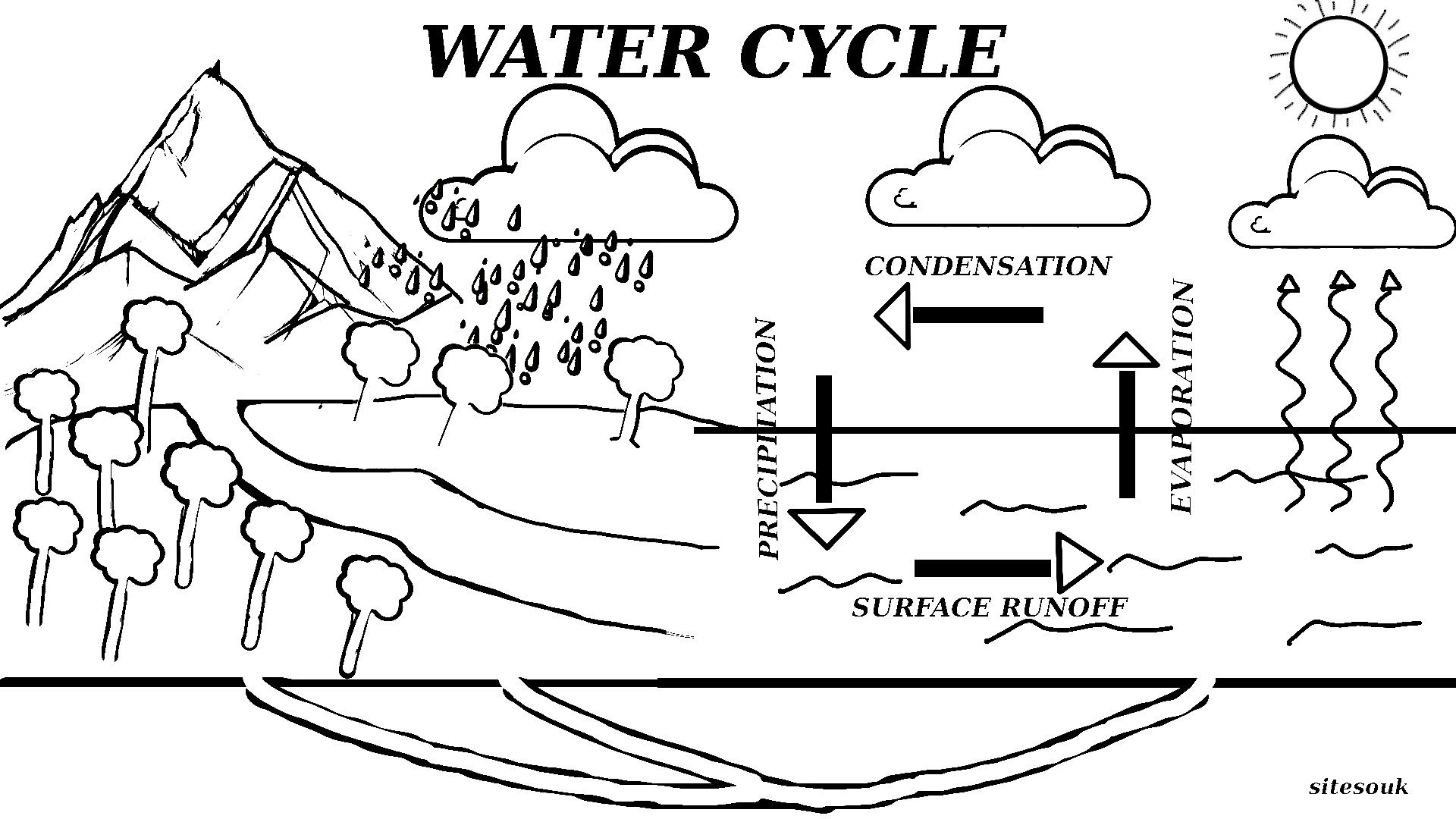

You’ve seen them since second grade. Those bright, circular diagrams with a fluffy blue cloud, a mountain, and a happy little sun. They make it look so simple. Water goes up, water comes down, and it all happens in a perfect little loop. Honestly, most pictures of a water cycle you find in a quick image search are kinda lying to you. They miss the messy parts. They skip the groundwater that takes ten thousand years to move an inch. They ignore the fact that humans have poked so many holes in this "cycle" that it’s more like a leaky bucket now.

Science is rarely as neat as a graphic designer's layout.

If you’re looking for a picture to teach your kids or use for a project, you have to be careful. A bad diagram isn't just a "simplified" version; it can actually bake in misconceptions that stick with people for life. For instance, did you know most people think the ocean is the only place water evaporates from? Total myth. Plants are basically giant straws sweating water back into the sky, but they’re usually just a tiny green blob in the corner of these illustrations.

The Problem With the "Perfect Circle"

Most pictures of a water cycle show a loop. It’s comforting. It suggests that water is never lost, just moved. While technically true on a planetary scale—thanks, Law of Conservation of Mass—it’s misleading for how we actually experience life on Earth.

When you look at a standard diagram, you see evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. Boom. Done. But that overlooks the "residence time." This is a huge concept in hydrology. A molecule of water might spend nine days in the atmosphere. That same molecule, if it falls over the Antarctic, might stay frozen in a glacier for 100,000 years. If it seeps into a deep aquifer, it’s out of the "loop" for millennia. A simple 2D drawing can't really capture that kind of time. It makes it look like the rain that falls today was the puddle that evaporated yesterday. It wasn't.

Where is the Groundwater?

This is a pet peeve for hydrologists like those at the USGS (U.S. Geological Survey). In older pictures of a water cycle, the ground is just a solid brown slab. Maybe there’s a little blue line for a river. In reality, there is vastly more liquid freshwater underground than there is in all the world's lakes and rivers combined. About 99% of it, actually.

When diagrams skip the infiltration process or the complexity of aquifers, they fail to show how we get our drinking water. We’re pumping that water out faster than the "cycle" can put it back. That’s a detail you won’t find in a clip-art version of the water cycle. You need to look for diagrams that show the "saturated zone" and the "water table." If the picture doesn't show water moving through the soil, it's basically a fairy tale.

👉 See also: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

Humans Are Now Part of the Plumbing

If you find a picture of a water cycle that doesn't have a city, a farm, or a dam in it, it’s outdated. Period. We aren't just bystanders watching the rain. We are active participants. We divert rivers. We create massive reservoirs that change how much water evaporates in a specific region.

- Irrigation: We pull water from the ground and spray it over crops, which changes local humidity.

- Urbanization: Concrete doesn't let water soak in. In a "natural" picture, water seeps into the earth. In a city, it hits the asphalt and zooms into a storm drain.

- Deforestation: Trees are water pumps. When we cut them down, we stop "transpiration," which can actually lead to less rainfall in that area.

National Geographic and the USGS have actually started redesigning their official pictures of a water cycle to include these human impacts. They realized that teaching kids a "pristine" cycle was actually dangerous because it made it seem like the water supply was infinite and untouchable. It’s not. We are the biggest "pump" in the system now.

What a "Good" Diagram Actually Looks Like

So, what should you actually look for? If you're scouring the web for a visual that isn't garbage, check for these specific features.

First, look for Transpiration. If the diagram just says "evaporation" over the ocean, keep scrolling. You want to see "Evapotranspiration." It’s a mouthful, sure, but it’s the combined process of water evaporating from the soil and "breathing" out of plants. It accounts for about 10% of the moisture in the atmosphere.

Second, check the Sublimation. This is the cool part where ice turns directly into vapor without melting first. Think of the "steam" coming off a block of dry ice. This happens on Mount Everest and in the Andes. If a diagram includes it, the creator actually knew their stuff.

Third, look at the Atmospheric Rivers. These are basically giant "rivers in the sky" that carry more water than the Amazon. They are responsible for most of the heavy rain on the West Coast of the U.S. and in parts of Europe. Most pictures of a water cycle just show a generic cloud. A sophisticated one will show these long, narrow bands of moisture transport.

✨ Don't miss: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

The Missing Ocean Depth

The ocean isn't just a flat blue tank. It has layers. The "mixed layer" at the top is where most evaporation happens, but there are deep-sea currents that move water around the globe over the course of 1,000 years. This is the "Great Ocean Conveyor Belt." If a water cycle picture shows the ocean as just a starting point for evaporation, it’s missing the engine that drives the whole thing. The heat stored in the ocean is what pushes the water vapor into the air in the first place.

Why Scale Matters (And Why Most Pictures Fail)

Scale is the hardest thing to draw. If you made a scientifically accurate picture of a water cycle to scale, the atmosphere would be a thin film thinner than a coat of paint on a basketball. The mountains would be barely visible bumps.

Because we have to "zoom in" to see anything, we lose the sense of where the water actually is.

- 97% is in the ocean (salty).

- 2% is frozen in glaciers and ice caps.

- Less than 1% is the freshwater we can actually use.

Most pictures of a water cycle make it look like there’s an equal amount of water everywhere—the river looks as big as the ocean, and the clouds look like they hold oceans of water. They don't. The atmosphere holds a tiny, tiny fraction of Earth's water. It’s just that it moves through the atmosphere very quickly. It's high turnover, low inventory.

Using Pictures of a Water Cycle for Real Learning

If you are a teacher or a student, don't just look at one picture. Compare three.

Take a "natural" diagram and lay it next to a "human-impact" diagram. Ask why the river in one is straight and the river in the other has a dam. Look at how the "runoff" is handled. In a forest, runoff is slow. In a city diagram, runoff is a literal flood.

🔗 Read more: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

You can also find "biogeochemical" versions. These are the "pro" level pictures of a water cycle. They show how water moves chemicals—like nitrogen or phosphorus—around the planet. This is how we get "dead zones" in the Gulf of Mexico. The water picks up fertilizer from farms in the Midwest, carries it down the Mississippi, and dumps it into the ocean. The water cycle isn't just moving H2O; it's a global delivery service for everything dissolved in it.

Surprising Fact: Fossil Water

Some diagrams are starting to include "fossil water." This is water that was trapped underground during the last ice age or even earlier. It's not part of the "cycle" anymore because it doesn't get replenished. Once we pump it up to grow corn in Kansas, it's gone from that source forever. It enters the atmosphere and eventually ends up in the ocean, but it won't go back into that deep aquifer for millions of years. This is why the "circle" metaphor is breaking down. We are turning a cycle into a one-way street in many places.

Practical Steps for Finding or Creating Better Visuals

Stop using Google Images blindly. Most of the top results are SEO-optimized garbage from 2012 that haven't been updated with modern climate data.

Instead, head to the NASA Earth Observatory. They have visualizations based on satellite data (like the GRACE mission) that show how water mass actually moves around the planet. You can see the Earth "breathing" water vapor in real-time.

If you're making your own pictures of a water cycle, try these specific tweaks to make it "human-quality":

- Ditch the perfect circle. Draw arrows of different thicknesses to show that more water stays in the ocean than goes into the air.

- Add the "invisible" water. Use a cross-section to show the massive amount of water stored in the rocks beneath our feet.

- Put humans in the middle. Add a small town or a farm. Show the pipe going into the ground and the drain going into the river.

- Label the "Residence Times." Put "9 days" next to a cloud and "1,000 years" next to the deep ocean. It changes how people perceive the "speed" of nature.

The water cycle isn't a static thing we can just draw and forget. It’s a shifting, living system that we are currently re-wiring. If your pictures don't reflect that complexity, they aren't teaching science—they're just decorating a page. Look for the messy, the human, and the deep. That's where the real story is.

To get the most out of these visuals, start by identifying the specific "leak" in your local water cycle—whether it's an over-tapped aquifer or a paved-over wetland—and map out where that water actually goes once it hits the storm drain. Browse the latest USGS interactive maps to see how the cycle is currently behaving in your specific zip code.