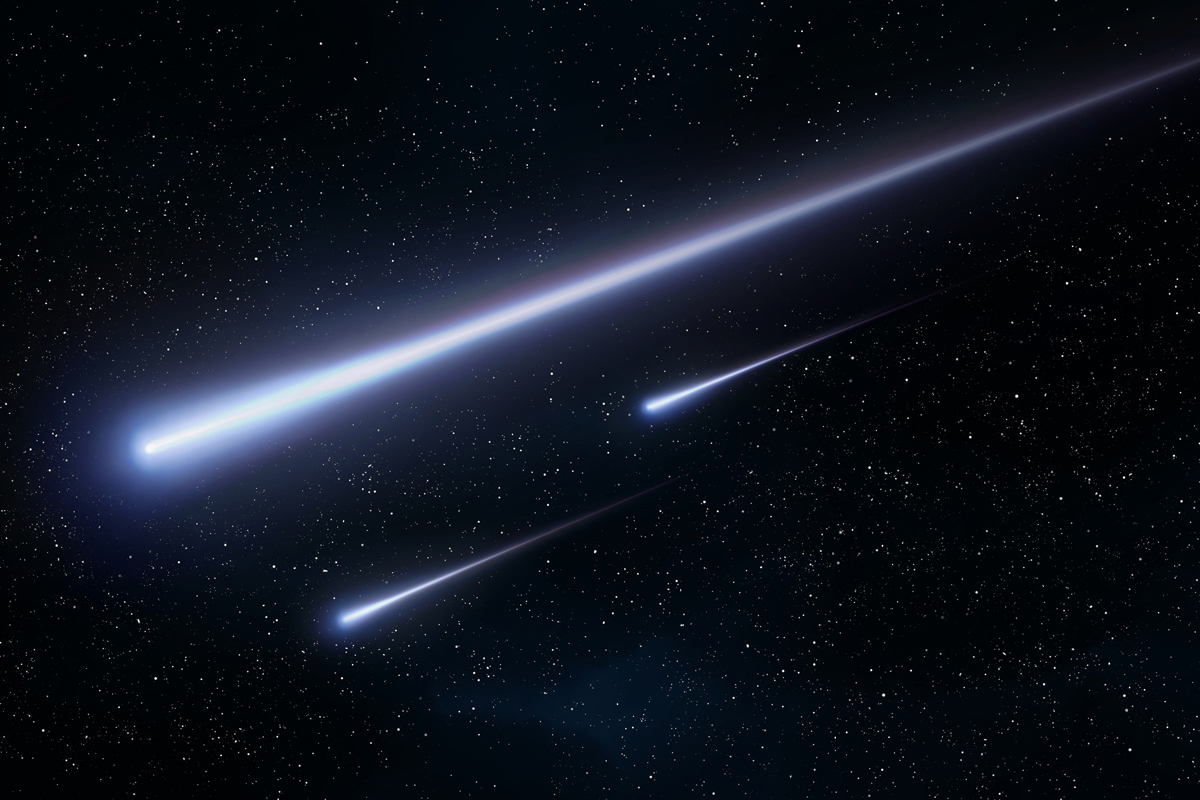

You’ve been there. You’re standing in a freezing field at 3:00 AM, neck cramped from staring at the Perseids, and suddenly a green streak tears across the sky. It’s huge. It’s electric. You immediately grab your phone or your DSLR, snap a frame, and look at the screen. Nothing. Just a grainy, black rectangle that looks like a photo of the inside of a pocket. Honestly, it’s frustrating.

Capturing pictures of a meteor shower is probably one of the most humbling experiences in photography because the human eye is a liar and your camera is a literalist. We see the "afterglow" and the movement, but the camera only sees light hitting a sensor for a fraction of a second. If you want those National Geographic-style shots where the sky looks like it’s exploding with light, you have to stop thinking like a photographer and start thinking like a data collector.

The Technical Lie of the Single Shot

Most people think they can just wait for a flash and hit the shutter. You can’t. By the time your brain signals your finger to press the button, the meteor is gone. It traveled at 40 miles per second. You missed it.

To get real pictures of a meteor shower, you have to use long exposures. We’re talking 15, 20, or 30 seconds. But even then, a single 20-second shot usually only catches one meteor if you’re lucky. That famous "starburst" effect you see online? That is almost always a composite. Photographers like Babak Tafreshi or the folks over at Sky & Telescope don't just take one photo. They take five hundred. Then they stack them.

Why Your Phone is Struggling

Smartphone sensors are tiny. They’re getting better, sure, with "Night Mode" and computational photography, but they still struggle with thermal noise. When you leave a phone sensor on for a long time, it gets hot. Heat creates "hot pixels"—those annoying red and blue dots that aren't stars. If you’re using an iPhone or a Pixel, you basically need a tripod. There is no way around the tripod. Even the tiniest tremor from your heartbeat will turn a sharp star into a blurry noodle.

🔗 Read more: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

Setting Up for the Geminids or Perseids

If you’re serious, you need to find the "radiant." This is the point in the sky where the meteors seem to originate. For the Perseids, it’s the constellation Perseus. For the Geminids in December, it’s Gemini.

But here’s the kicker: don't point your camera directly at the radiant.

Meteors near the radiant have short tails because they are coming almost directly at you. If you want those long, dramatic streaks that fill the frame, point your camera about 30 to 45 degrees away from the radiant. That’s where the "earthgrazers" happen. These are meteors that skim the upper atmosphere and leave trails that last for several seconds.

Gear that Actually Matters

- A Wide-Angle Lens: Think 14mm to 24mm. You want to see as much sky as possible to increase the mathematical odds of a meteor crossing your sensor.

- Fast Aperture: You need an f/2.8 or wider. If you're shooting at f/4, you’re losing half the light. Meteors are fast; they don't give the sensor much time to "soak up" their glow.

- An Intervalometer: This is a little remote that tells your camera to take a picture, wait one second, and take another one. Forever. Or until your battery dies.

The Boring Truth About Post-Processing

Let’s talk about "stacking." This is the secret sauce for pictures of a meteor shower.

💡 You might also like: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

When you see a photo with 50 meteors in it, the photographer took 500 photos over six hours. They then used software like Starry Landscape Stacker or Sequator. These programs align the stars (because the Earth is rotating, obviously) and then "mask" in only the meteors from each frame. It’s a tedious process. It’s not "fake," but it is a compression of time. It shows the entire night’s activity in a single image.

Dealing with Light Pollution

If you are trying to do this in the suburbs, stop. You’re wasting your time. You need to look at a light pollution map (like Dark Site Finder) and get to at least a "Bortle 3" zone. In a city, the sky is too bright. If you try a 20-second exposure in Los Angeles, the sky will just look orange. White. Blank. You need the contrast of a truly dark sky to make the faint magnesium-burn of a meteor pop against the background.

Common Mistakes Beginners Always Make

I’ve seen people try to use flash. Don't be that person. Flash does nothing for an object 60 miles up in the atmosphere, and it ruins your night vision (and everyone else's around you).

Another big one: forgetting to turn off Image Stabilization (IS or VR). When your camera is on a tripod, the stabilization mechanism tries to find movement that isn't there. It ends up creating a weird feedback loop that actually makes your stars blurry. Turn it off.

📖 Related: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

Also, focus. Your camera cannot autofocus on stars. It will hunt back and forth and eventually give up. You have to switch to Manual Focus, turn on "Live View," zoom in on a bright star like Sirius or Vega, and turn the ring until the star is the smallest possible point of light. If it looks like a little donut, you’re out of focus.

Why 2026 is a Weird Year for Sky Photos

Depending on the moon cycle, your pictures of a meteor shower might be washed out. The moon is the ultimate light polluter. If there’s a full moon during the peak of the Leonids, for instance, you’re basically shooting in daylight. You have to wait for the moon to set or shoot in the narrow window before it rises.

A lot of people think they need the most expensive Sony A7SIII or a Nikon Z9. You don't. An old Canon 5D Mark II or a mid-range crop sensor camera like a Fuji X-T3 can do this perfectly well. It’s more about the glass and the patience than the sensor.

Essential Steps for Your Next Outing

- Check the Weather Twice: Clouds are the enemy. Use an app like Astropheric; it shows cloud cover at different altitudes.

- Bring Extra Batteries: Long exposures at night drain batteries fast, especially if it’s cold. Keep spares in your pocket close to your body heat.

- Use a Lens Heater: If you’re in a humid area, your lens will fog up in an hour. A simple USB-powered dew heater strip is a lifesaver.

- Format to RAW: Never shoot JPEGs of the night sky. You need the raw data to recover the shadows and fix the white balance later.

- Interval Settings: Set your camera to take continuous shots. If you take 30-second exposures with a 1-second gap, you’ll cover 97% of the night.

To actually walk away with a portfolio-grade shot, you have to embrace the volume game. You might take 400 photos and find that 398 of them are just empty stars or a stray satellite. That’s normal. The goal is to catch that one "bolide"—a fireball that explodes and leaves a persistent train of ionized gas. When you catch one of those on a clean, wide-angle RAW file, the effort of standing in a dark field at 4:00 AM suddenly makes total sense.

Pack your gear, find a clearing with a wide view of the horizon, and set your focus to infinity manually before the sun goes down to save yourself the headache later. Once the camera is clicking away, just sit back and look up. The best view isn't on the LCD screen anyway.