You’ve probably seen them in every middle school textbook. Those neat, symmetrical butterfly wings made of iron filings. It’s the classic way to get pictures of a magnetic field, and honestly, it’s a bit of a lie. Well, not a lie, exactly, but a massive oversimplification. It’s like looking at a stick figure and thinking you understand human anatomy.

Magnetism is invisible. That’s the first hurdle. You can’t "photograph" a magnetic field any more than you can photograph the wind. You can only photograph what it does to things. Whether it's iron dust on a piece of paper or superheated plasma looping off the surface of the sun, we are always looking at the footprints, never the feet.

The Iron Filing Trap

Let's talk about those iron filings. It’s the most common way people try to visualize magnetism. You drop a bar magnet under a sheet of glass, sprinkle some shavings, and—presto—you have a visual.

But here is the thing: the filings themselves change the field. Each little speck of iron becomes its own tiny magnet when it enters the field. They clump together. They create lines where there aren't actually "lines." In reality, a magnetic field is a continuous, smooth gradient. It’s a vector field. There are no gaps between the lines in nature; it’s a solid wall of force that gets weaker as you move away.

The "lines" are just a mathematical convenience we’ve turned into a visual trope. Michael Faraday, the self-taught genius who basically birthed our understanding of electromagnetism, used these "lines of force" to help his intuition because he wasn't a math guy. He needed to see it. And because he saw it that way, we’ve been looking at it that way since the 1830s.

How NASA Actually Maps the Sun

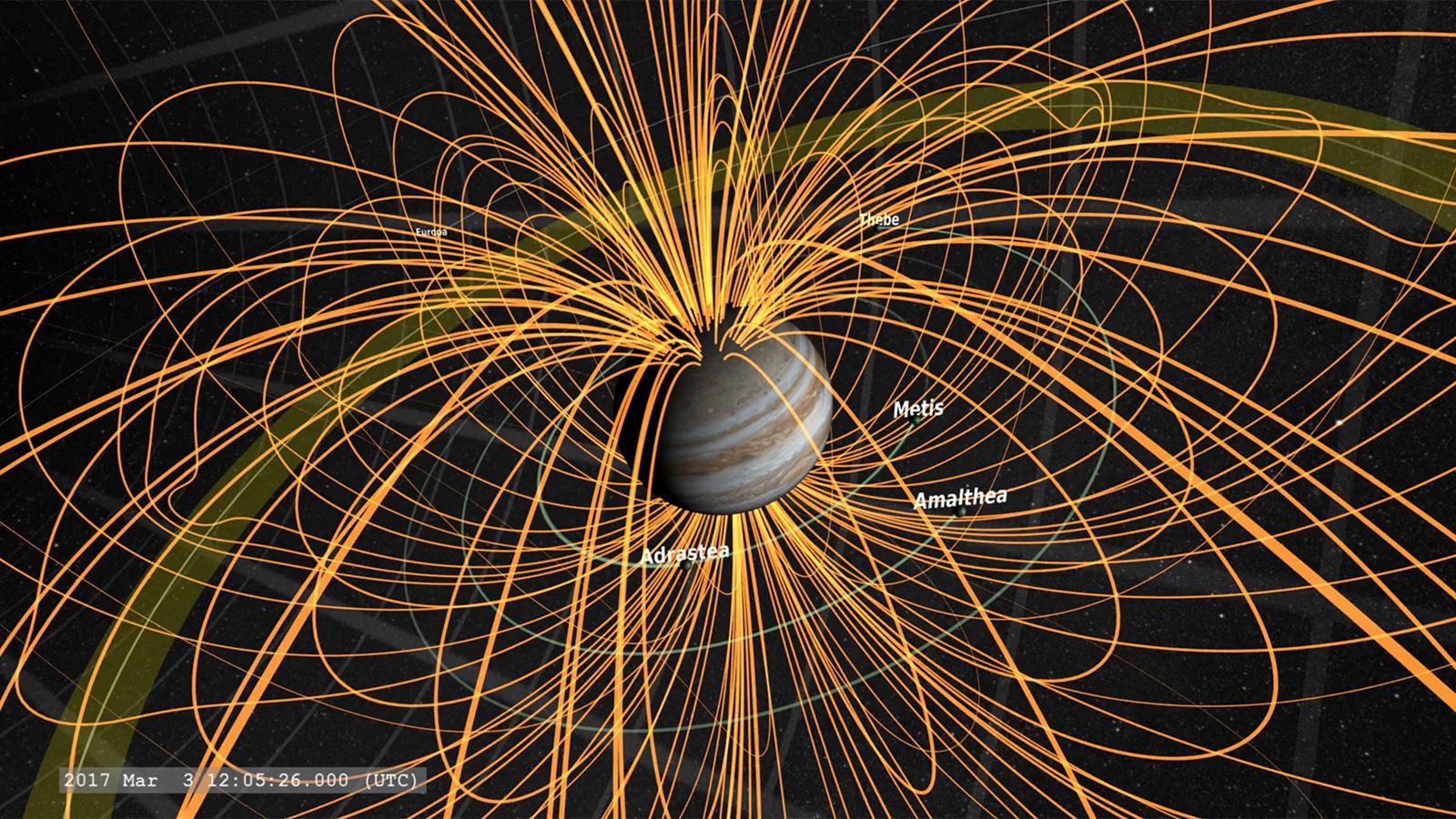

If you want the really high-end pictures of a magnetic field, you have to look at the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). The Sun is basically a giant, messy ball of magnetic chaos.

NASA doesn’t just snap a photo and call it a day. They use something called a Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI). It measures the Zeeman effect. Basically, when a gas is stuck in a strong magnetic field, the light it emits gets split into different frequencies. By measuring that split, scientists can calculate the strength and direction of the field.

💡 You might also like: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

Then, they use "potential field source surface" (PFSS) models to draw the loops. When you see those glowing, golden loops of fire on NASA's website, you’re seeing a mix of actual glowing plasma and computer-generated lines that follow the calculated magnetic path. It’s a map of a ghost.

The Problem with Color

In almost every professional image of a magnetic field, the colors are fake. They have to be.

- Blue and Red: Usually indicates polarity (North vs. South).

- Brightness: Often represents field intensity or "flux density."

- Green/Yellow Loops: In solar photography, these often represent different temperatures of plasma trapped in magnetic "bottles."

Without these artificial colors, the data would just be a series of numbers in a spreadsheet. It’s a translation from the language of physics into the language of human eyes.

Ferrofluid: The Trippy Reality

If you want to see what a magnetic field looks like in 3D without the "flat" lie of iron filings, look at ferrofluid. It’s a "colloidal suspension"—basically nano-scale bits of magnetite floating in oil.

When you bring a magnet close to it, the liquid doesn't just move; it spikes. It looks like a metallic hedgehog. This happens because of a fight between surface tension and magnetic force. The spikes follow the field lines out into three-dimensional space. It’s probably the closest we can get to "seeing" the shape of the force in our own living rooms.

It’s messy. It stains everything. But it’s real.

📖 Related: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a Giant Camera

We don't usually think of an MRI scan as a picture of a magnetic field, but that’s exactly what it is. An MRI machine uses a massive superconducting magnet—usually around 1.5 to 3 Teslas. For context, that’s about 30,000 times stronger than the Earth's magnetic field.

The machine aligns the protons in your body. Then it hits them with radio waves to knock them out of alignment. As they snap back into place, they emit a signal. The "picture" is a map of how the protons reacted to the magnetic field in different tissues.

If the magnetic field wasn't perfectly calibrated and visualized by the software, the image would be a blurry mess. Doctors are essentially using magnetic geometry to see through your skin.

The Earth’s Shield

We also have to talk about the magnetosphere. This is the big one. It’s the only reason we aren't being fried by solar radiation right now.

We can't take a "photo" of the Earth's magnetic field from space because it’s invisible and massive. It stretches thousands of miles into vacuum. But we see it during the Aurora Borealis. Those greens and purples? That’s the solar wind hitting the "walls" of our magnetic field and trickling down toward the poles.

The Aurora is literally a fluorescent light bulb the size of a planet, and the "filament" is the Earth’s magnetic field. When you look at a photo of the Northern Lights, you are looking at a cross-section of a planetary defense system.

👉 See also: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

The Tech Behind the Visualization

How do we get these images without using iron dust or giant space telescopes?

- Magneto-optical sensors: There are special films that change color based on magnetic orientation. You lay them on a credit card or a motor, and you can see the encoded magnetic "bits."

- SQUID Microscopes: No, not the animal. Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices. These can sense magnetic fields so weak they’re produced by the firing of a single neuron in your brain.

- Electron Holography: This is the peak of the craft. Scientists use electron beams to "see" the magnetic fields inside of individual atoms.

Why Most Digital Renders are Wrong

If you search for pictures of a magnetic field on a stock photo site, you'll see a lot of glowing neon grids. They look cool. They look like The Matrix.

But they usually get the physics wrong. Magnetic fields don't have sharp corners. They don't just "stop." They fade out according to the inverse-square law. Most digital artists draw them like light beams, but they act more like pressurized fluid.

If you want to know if a visualization is accurate, look at the poles. The lines should be densest right at the surface of the magnet and spread out rapidly. If the lines are perfectly parallel, it’s probably a fake or a very specific "uniform field" created by a Helmholtz coil.

A Quick Reality Check on Magnets

- Monopoles don't exist: You can't have a North without a South. If you break a magnet in half, you just get two smaller magnets. Every picture of a magnetic field should show loops, never a single line pointing away into nothingness.

- They aren't "pulling" everything: Only "ferromagnetic" materials really react strongly. Most things are "diamagnetic" (weakly repelled) or "paramagnetic" (weakly attracted). If you had a strong enough magnetic field—like the ones at the High Field Magnetic Laboratory in the Netherlands—you could actually make a frog levitate. And yes, there are pictures of that. It’s hilarious and scientifically profound.

- The Field is Constant: A magnet isn't "using up" its field to hold a picture on your fridge. It’s a static property. The "picture" of the field doesn't change unless the temperature changes or you hit it with a hammer.

Seeing the Unseen

At the end of the day, looking at pictures of a magnetic field is an exercise in imagination. We are trying to visualize a fundamental force of the universe using the limited tools of our retinas.

Whether it's the grainy black-and-white images from an electron microscope or the vivid, violent purples of a solar flare, these images are translations. They take the invisible math of the universe and turn it into something we can understand.

If you want to try this at home without the mess of iron filings, grab an old smartphone. Most of them have a "hall effect" sensor inside for the compass. Download a "Magnetic Field Sensor" app. It won't give you a pretty picture, but it will give you a live graph of the invisible waves passing through your room right now.

Actionable Insights for Visualizing Magnetism

- For Educators: Avoid using 2D diagrams exclusively. Use 3D models or ferrofluid displays to show that magnetism isn't just "lines on paper"—it's a volume of space.

- For Photographers: To capture the Aurora, use a wide-angle lens (14mm to 24mm) and a long exposure (5-15 seconds). You aren't just photographing light; you're photographing the Earth's magnetic shield reacting to the sun.

- For Tech Enthusiasts: If you're inspecting magnetic storage or hardware, use magnetic viewing film (available cheaply online). It’s a green translucent sheet that reveals the "hidden" poles on any magnetic surface instantly.

- For Curious Minds: Look up the "MagLab" photo galleries. The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory has some of the most scientifically accurate visualizations of high-intensity fields ever produced.

The next time you see a bar magnet with those perfect little lines, remember that the reality is much weirder, much more fluid, and significantly more chaotic. The universe doesn't draw in straight lines, and it certainly doesn't stay inside the margins.