You’ve seen them a thousand times. The green leaf, the striped crawler, the little green "J," and then the explosion of orange and black wings. Standard stuff. Most pictures of a butterfly life cycle look like they were pulled from a 1990s textbook, sanitized and simplified until the actual magic is squeezed out of them. But if you're out in your garden with a macro lens or just stalking a milkweed patch in the park, you realize pretty fast that the reality is way messier. It’s also much cooler than the posters suggest.

Metamorphosis isn't just a change of clothes. It’s a complete biological teardown. Imagine taking a Lego castle, smashing it into a pile of bricks, and then rebuilding it into a functioning jet engine using the exact same pieces. That is what’s happening inside that chrysalis.

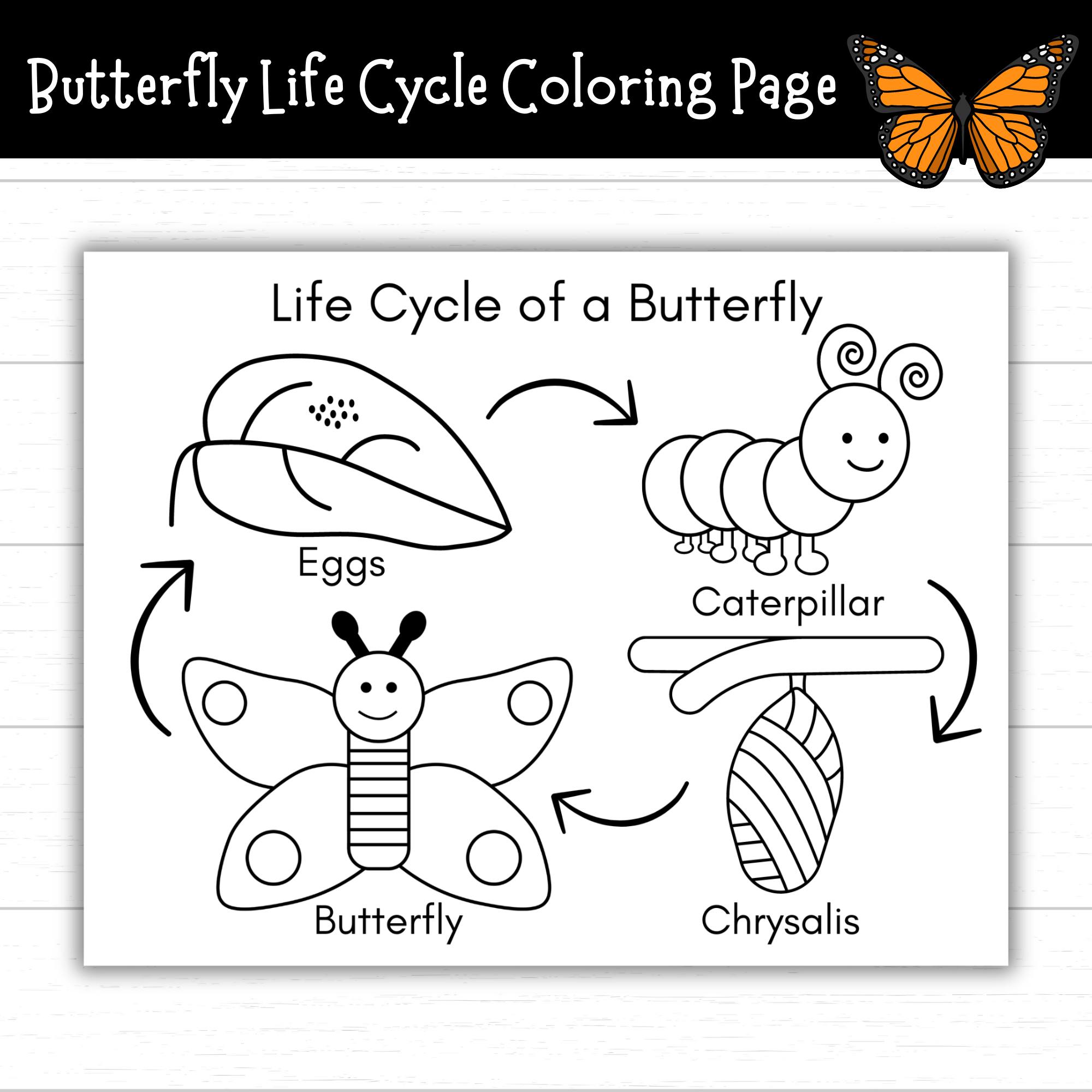

Most people think they know the four stages: egg, larva, pupa, adult. Sure, that’s the curriculum. But honestly, the tiny details—the stuff most cameras miss—are where the real story lives.

The Egg Stage: More Than Just a Speck

When you’re hunting for pictures of a butterfly life cycle, the egg usually gets the short end of the stick. It’s tiny. It’s boring. Except, it isn't. If you zoom in—like, really zoom in with a microscope or a high-end macro setup—you see these aren't just white dots. Monarch eggs, for instance, look like tiny, ribbed silver footballs. They’re glued to the underside of milkweed leaves with a biological adhesive that would make a chemical engineer jealous.

It only lasts about three to five days.

Timing is everything here. If a photographer isn't there at the exact moment of eclosion (the fancy word for hatching), they miss the first meal. The caterpillar doesn't go for the leaf first. It eats its own eggshell. It’s packed with protein and it’s the baby’s first "no waste" move. If you see a photo of a tiny larva next to a perfectly intact shell, it’s probably a setup. In the wild, they clean their plates.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

The Larva Phase: A Professional Eating Machine

The caterpillar stage is basically just an eating contest where the prize is not dying. This is where most pictures of a butterfly life cycle start to get interesting because of the colors. But what a lot of people don't realize is the concept of "instars." A caterpillar doesn't just grow like a human does. Its skin doesn't stretch. It reaches a limit, splits its skin down the back, and crawls out in a new, roomier version.

Most butterflies go through five instars.

Between these stages, the caterpillar looks a bit pathetic. It stops eating. It sits still. It’s vulnerable. Photographers usually skip this because "static bug on leaf" doesn't get the clicks, but this is the heavy lifting of growth. By the time a Monarch caterpillar is ready to pupate, it has increased its body mass by about 2,000 times. If a human baby grew at that rate, it would weigh several tons within a couple of weeks. Think about that next time you see a chubby yellow-and-black crawler.

Survival Tactics You Might Have Missed

It isn't all just munching on leaves. It's war out there.

- Mimicry: Some swallowtail caterpillars look exactly like bird droppings in their early stages. Seriously. Evolution decided that looking like poop was the best way to not get eaten by a robin.

- Chemical Warfare: Monarchs sequester cardenolides (heart poisons) from milkweed. They aren't just colorful; they’re toxic.

- The Osmeterium: If you poke a giant swallowtail caterpillar, a bright orange, Y-shaped organ pops out of its head and it smells like rancid butter. It’s a terrifyingly effective way to tell a predator to back off.

The Pupa: The Great Disappearing Act

This is the part everyone gets wrong. You'll hear people call it a "cocoon." Stop. Unless it’s a moth, it’s a chrysalis. Moths spin silk (a cocoon); butterflies harden their own skin (a chrysalis).

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

When you look at pictures of a butterfly life cycle featuring the chrysalis, it looks like a peaceful little sleeping bag. It’s not. Inside, the caterpillar’s body is releasing enzymes called caspases that literally dissolve its own tissues. It turns into a nutrient-rich soup. The only things that stay intact are "imaginal discs"—tiny clusters of cells that have been sitting dormant inside the caterpillar since it was an egg. These discs use the "caterpillar soup" as fuel to build wings, legs, and complex eyes.

It’s a literal rebirth.

If you’re trying to photograph this, the "J-hang" is your warning light. The caterpillar finds a spot, spins a silk button, and hangs upside down. It stays there for hours. Then, in a frantic minute or two, the skin splits, the green shell underneath hardens, and the transformation begins. If you blink, you’ll miss the best shot of the entire cycle.

The Imago: Coming Out Party

The final stage—the adult, or "imago"—is what everyone wants on their memory card. But have you ever seen a photo of a butterfly five seconds after it emerges? It looks like a wreck. Its wings are tiny, wet, and shriveled. It looks like it failed.

The butterfly has to pump fluid (hemolymph) from its bloated abdomen into the veins of its wings. It’s a hydraulic process. If it falls during this time, or if the wings dry before they’re fully expanded, it will never fly. It’s a high-stakes moment that lasts about 20 minutes to an hour.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Most pictures of a butterfly life cycle show the finished product: a pristine, dry butterfly on a flower. But the real drama is that soggy, desperate struggle to inflate those wings before a predator notices the bright orange snack hanging from a twig.

Why Do They Do It?

The adult stage is strictly for two things: moving and mating. Most adult butterflies only live for two to four weeks. The exception is the "Methuselah" generation of Monarchs that migrates to Mexico; those guys can live for eight months. But for your average Painted Lady or Tiger Swallowtail, the clock is ticking. They don't even "grow" anymore. They just drink nectar for energy to keep the search for a mate going.

Capturing the Life Cycle: Real-World Tips

If you’re trying to document this yourself, don't just buy a kit and do it indoors. Indoor lighting makes for "sterile" photos. Go outside. Find a patch of native plants.

- Look for the "chew": If you see a leaf with semi-circular notches, something is living there. Turn the leaf over.

- Golden Hour is a lie for bugs: You actually want slightly overcast days or early mornings. Early morning is best because butterflies are cold-blooded. They move slowly when it’s 60 degrees. Once the sun hits them and they "warm up," they’re gone before you can focus.

- Macro is hard: You don’t need a $2,000 lens. A simple "extension tube" for your existing camera or even a clip-on macro lens for your phone can get you close enough to see the scales on the wings.

What Most People Miss

The interaction between the butterfly and the ecosystem is usually cropped out of pictures of a butterfly life cycle. We focus on the bug, but the plant matters just as much. Host plants are specific. A Monarch only eats milkweed. A Gulf Fritillary only eats passionflower. If you take a photo of a butterfly on a "pretty" flower that isn't its host, you’re only seeing half the story.

Also, the mortality rate is staggering. Out of 100 eggs laid, maybe two or three make it to the butterfly stage. Spiders, wasps, birds, and even bacterial infections take out the rest. When you see that one perfect butterfly, you’re looking at a survivor of a brutal gauntlet.

Practical Steps for Better Observations

If you want to move beyond just looking at pictures of a butterfly life cycle and actually see it happen, here is what you do.

- Plant the right stuff. Stop mowing a small corner of your yard. Plant native milkweed, parsley, or dill. These attract "Specialists" that stay in one spot.

- Get a loupe. A jeweler’s loupe (those 10x magnifying glasses) costs about ten bucks. Looking at a chrysalis through one of those is like looking at another planet.

- Check the "cremaster." When the caterpillar is about to turn into a chrysalis, it uses a tiny Velcro-like hook called a cremaster to stay attached. Finding that connection point in a photo is the mark of a pro.

- Watch the eyes. In the final hours before a butterfly emerges, the chrysalis becomes transparent. You can actually see the wing patterns and the compound eyes through the shell. That's your signal to get the camera ready.

The life cycle isn't a circle; it’s a series of narrow escapes. Most photos make it look easy. It’s anything but. By focusing on the transitions—the "ugly" parts where things melt, shed, and struggle—you get a much more honest view of what it takes to actually become a butterfly. It's a messy, violent, and beautiful process that happens right under our noses, usually on the underside of a leaf we were about to trim.