If you search for pics of the trail of tears, you’re going to find a lot of results. You’ll see oil paintings of weary families in the snow. You'll see black-and-white sketches of soldiers on horseback. You might even see some grainy, old-looking photos of people in wagons. But here is the thing that catches most people off guard: none of those photos are real.

Not a single one.

Photography wasn’t a thing during the forced removals of the 1830s. The technology literally didn't exist in a portable, usable way. Louis Daguerre didn't even announce the daguerreotype process until 1839, which was just as the primary Cherokee removals were wrapping up. So, when we talk about images of this era, we are talking about memory, recreation, and sometimes, flat-out historical confusion.

The Timeline Problem with Photography

History is messy. We’re so used to seeing the Civil War in crisp, haunting detail thanks to Matthew Brady, so we naturally assume we can see the Trail of Tears too. But that decade of difference—the 1830s versus the 1860s—is a massive gulf in technological history.

During the Indian Removal Act’s peak execution, if you wanted a "picture," you needed a painter. You needed someone like Robert Lindneux or Max D. Standley, but even they weren't there. Lindneux’s famous painting, which shows the Cherokee moving through a bleak, frozen landscape, wasn't painted until 1942. That's over a century after the fact. It’s a powerful piece of art, but it’s a reconstruction based on oral histories and historical records, not a primary visual source.

People often mistake late 19th-century photos of Indigenous people for pics of the trail of tears. You’ve probably seen the portraits taken by Edward S. Curtis or photos of Oklahoma "land runs." Those are real photos, sure, but they were taken 50 to 70 years after the removal. By the time cameras were common in the American West, the survivors of the original Trail were elderly or had already passed away.

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

What the Archives Actually Hold

So, if there aren't photos, what do we actually have? We have the written word. We have the journals of the soldiers who felt guilty about what they were doing. We have the letters of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creeke), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw people who were being pushed off their ancestral lands.

The "visuals" of the Trail of Tears are mostly found in:

- Political Cartoons: These were the "photos" of the 1830s. They were often biting, cruel, or deeply sympathetic, appearing in newspapers like The Cherokee Phoenix or Northern publications that opposed Andrew Jackson.

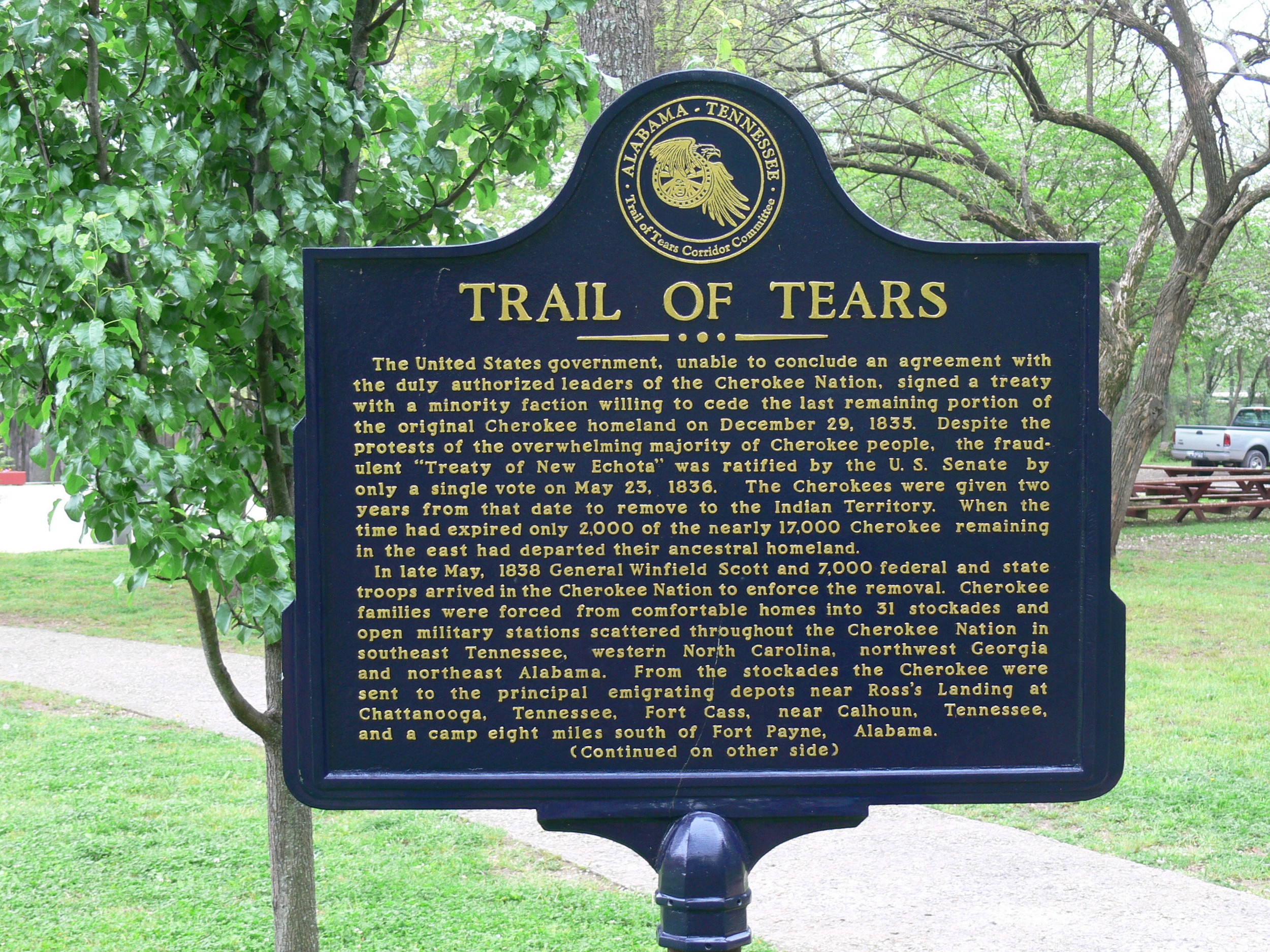

- Survey Maps: These are the most accurate "images" we have. The government kept meticulous records of the routes. When you look at a map from 1838, you aren't just looking at lines; you're looking at the exact path where thousands died.

- Modern Photography of the Sites: Today, the National Park Service maintains the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. Photographers today capture the "witness trees"—trees that were alive in 1838 and still stand today along the route.

It’s a weird feeling, standing in a spot in Southern Illinois or Missouri, looking at a quiet forest, and realizing that 13,000 people passed through that exact gap in the trees under the worst conditions imaginable. You don't need an old photo to feel the weight of that.

Misconceptions in Digital Archives

If you go to a site like Getty Images or Alamy and type in our keyword, you'll get hits. But look closely at the captions. Most are "engravings" or "lithographs." A lithograph is essentially a print made from a stone or metal plate. These were often made years later for history books.

One of the most famous images people cite is an engraving of a group of people crossing a river. It’s gritty. It looks real. But it was created for a 19th-century magazine long after the events took place. This matters because "pics" imply an objective truth that art can sometimes blur. Art adds emotion—it adds the dramatic snow and the weeping—which is all true to the experience, but it isn't a "snapshot."

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

The lack of actual pics of the trail of tears has actually hurt the public's understanding of the event. Humans are visual creatures. Without a "photo" to anchor the horror, it becomes an abstract concept for many students. It feels like a "long time ago" story rather than a documented human rights violation.

The Five Tribes and Their Individual Paths

It’s also a mistake to think there was just one "trail." There were many.

The Choctaw were first, starting in 1831. Then came the Seminoles, then the Muscogee, then the Chickasaw, and finally the Cherokee in 1838. Each of these migrations looked different. Some went by water on steamboats—which were often overcrowded and rife with cholera. Others walked. Some were chained.

If we had photos of the Choctaw removal in 1831, they would look different from the Cherokee removal of 1838. The weather was different. The terrain was different. The Choctaw faced a horrific winter that even moved some of the pro-removal soldiers to write home in disgust.

How to Find Authentic Visual Evidence Today

If you are a researcher or just someone who wants to see the truth, stop looking for "photos." Start looking for artifacts.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

The Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian has an incredible collection of items that actually went on the trail. We’re talking about hand-woven baskets, small bibles printed in the Cherokee syllabary, and personal jewelry. These objects are more "real" than any 1940s painting. They have the dust of the trail on them.

The Cherokee Heritage Center in Park Hill, Oklahoma, also houses primary documents that function as visual evidence. They have the pay vouchers. They have the lists of names. When you see a list of 1,000 names with "died" written in the margin next to 200 of them, that is a picture. It’s a data-driven picture of a tragedy.

Why the Search Persists

Why do people keep searching for pics of the trail of tears? Honestly, it’s probably because we want to connect. We want to look into the eyes of someone who survived it. We want to see the face of the resilience that allowed these nations to rebuild in Oklahoma and become the powerhouses they are today.

While we don't have their faces from 1838, we do have the faces of their descendants. Modern photography of Cherokee citizens today, many of whom are living on the very land their ancestors were forced onto, is the closest we get to a "sequel" to those missing photos.

Moving Forward With Historical Literacy

Understanding that there are no authentic pics of the trail of tears is the first step in truly respecting the history. It forces you to look deeper. It forces you to read the primary sources instead of just glancing at a thumbnail on a Google Search results page.

If you want to support the preservation of this history, there are several concrete things you can do right now.

- Visit the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail: This isn't just one spot. It’s a series of sites across nine states. Seeing the geography—the "Mantal Trail" in Missouri or the "Water Route" along the Tennessee River—provides a spatial context that no photo can.

- Support the Cherokee National Research Center: They are the ones doing the heavy lifting to digitize actual records from the era. These records are the most accurate "images" of the time.

- Check the Source: Next time you see a "photo" of the Trail of Tears on social media, check the date. If it’s a photo, it’s likely from the 1880s or later, or it’s a still from a movie like The Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy.

- Read "The Cherokee Phoenix": This newspaper was published before, during, and after the removal. It provides a contemporary "view" of the political and social climate that led to the removal.

The history isn't lost just because we don't have the film. It's just hidden in the archives, waiting for people to look past the modern "recreations" and find the hard, documented facts of what really happened on those roads to the West.