If you spend five minutes searching for photos of trail of tears, you’ll find plenty of images. You’ll see grainy, black-and-white shots of people wrapped in blankets, wagons trudging through mud, and tired families looking into the lens with haunting eyes.

Here is the problem. They aren't real.

Well, the people are real, but the timing is completely wrong. Most of those "famous" photos were actually taken decades after the forced removals ended. Some are even from the early 1900s, showing completely different events or general poverty in the South. It’s a bit of a historical mind-trip when you realize that one of the most documented tragedies in American history has almost zero visual record from the actual moment it happened.

We have diaries. We have government manifests. We have the physical graves. But actual, live-action photography? That just wasn't a thing yet.

The Massive Timeline Gap Most People Miss

History feels like one big "olden times" blur to a lot of us, but the dates matter. The primary forced removals of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, and Seminole nations mostly happened between 1830 and 1850.

Now, think about the camera.

Louis Daguerre didn't even introduce the daguerreotype to the world until 1839. Even then, it was a high-tech rarity. You couldn't just "snap" a photo. You needed a massive wooden box, toxic chemicals, and a subject who could sit perfectly still for several minutes. The idea of a photographer following the Cherokee on a 1,000-mile death march through the freezing woods of 1838 is, quite frankly, a fantasy.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

It didn't happen.

Most of the photos of trail of tears you see floating around Facebook or educational blogs are actually 1890s-era photos of "land runs" or 1930s-era re-enactments. Some are even Depression-era photos of displaced sharecroppers that someone slapped a "Trail of Tears" caption on because it looked "sad enough" to fit the vibe. This matters because when we use fake images to represent real pain, we sort of dilute the actual history of the people who were there.

What about the "Trail of Tears" paintings?

Since there are no photos, we rely on art. But even here, you have to be careful. The most famous painting—the one with the red-cloaked figures and the stoic faces—was painted by Robert Lindneux. He didn't paint it in 1838. He painted it in 1942. That’s over a century later.

Lindneux was a great researcher, and he tried to get the clothing and the weather right, but it's still an interpretation. It’s a memory of a memory. It isn't a primary source. If you’re looking for the "truth" of the event, looking at his painting tells you more about how 1940s Americans viewed the event than how 1830s Indigenous people experienced it.

The "Real" Visual Record is Hidden in Plain Sight

If we can't find photos of trail of tears from the 1830s, what do we actually have? We have portraits.

While photographers weren't on the trail, many Indigenous leaders had their portraits painted or taken as daguerreotypes when they went to Washington D.C. to negotiate treaties. These are the faces of the people who fought the Indian Removal Act in court.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

- John Ross (Guwisguwi): We have photos of him later in life. He was the Principal Chief who led the Cherokee through the removal. Seeing his face—a man who lost his wife, Quatie, on the trail—is much more powerful than looking at a grainy, mislabeled stock photo.

- Major Ridge: We have lithographs of him. He was one of the men who signed the Treaty of New Echota, believing removal was inevitable. He was later assassinated for it.

- The Artifacts: Museums like the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina hold the physical items—kettles, silks, and tools—that actually made the trip. These are the "photos" of the era. They are the physical proof.

Why the Mislabeling Happens

Honestly, it’s mostly laziness.

Content creators want a thumbnail. Teachers want a slide for a PowerPoint. They search for "Indigenous people walking" and grab the first thing that looks historical. This is how a photo of a Navajo person from 1904 ends up being used to represent a Cherokee person from 1838.

It’s also about the "Vanishing Race" myth. In the late 1800s, photographers like Edward Curtis went around trying to "capture" Indigenous life before it "disappeared." While Curtis’s work is artistically stunning, it was often staged. He’d give people clothes they didn’t normally wear or remove modern items from the shot to make them look more "authentic" and "primitive."

When people use these Curtis photos of trail of tears stand-ins, they’re accidentally participating in a narrative that Indigenous people are a thing of the past. But the nations that survived the trail—the "Five Civilized Tribes" and many others—are very much alive. They have governments, businesses, and TikTok accounts.

How to Verify Historical Photos

If you’re doing research and you come across a photo claiming to be from the removal era, run a quick mental checklist.

- Check the tech. Does it look like a modern "action shot"? If people are moving or blurring, it’s probably not from the early 1800s. Early photography required extreme stillness.

- Look at the clothes. By the 1830s, many Cherokee and Choctaw people wore a mix of traditional gear and European-style clothing. If everyone in the photo is dressed in Hollywood-style buckskins and massive headdresses, it’s likely a later re-enactment or a different tribe entirely.

- Reverse image search. This is the gold standard. Pop the image into a search engine. Often, you’ll find it’s actually a photo from the Library of Congress labeled "Oklahoma Land Rush, 1889."

The nuance of "Memory Photos"

There is one exception: photos of survivors.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, photography was common. There are actual photos of trail of tears survivors taken when they were very old. These are incredibly precious. You’re looking at a human being who, as a child, walked from Georgia to Oklahoma. Their faces are the closest we will ever get to a photographic record of the event.

The Smithsonian and various tribal archives hold these records. They aren't "action shots" of the march; they are portraits of resilience. They show people who built new lives in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) despite the government's attempt to erase them.

The Impact of Visual Misinformation

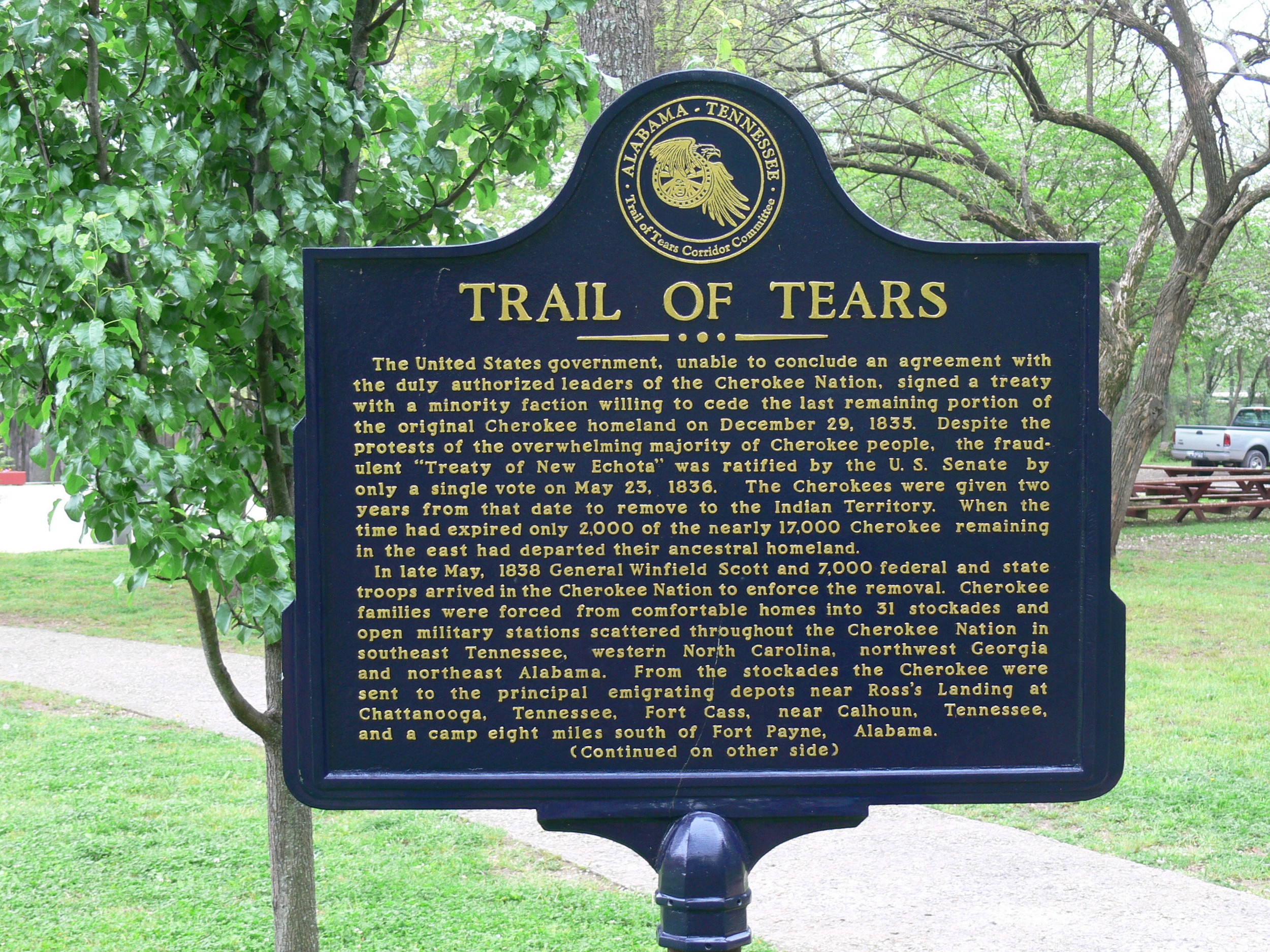

When we fill the internet with fake or mislabeled photos of trail of tears, we make it harder for people to understand the actual scale of the event. The removal wasn't just a "sad walk." It was a legal, political, and logistical catastrophe.

It involved the forced abandonment of homes, farms, and businesses. Using a photo of a random person in a tent doesn't capture the fact that the Cherokee had their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, and a written constitution before they were forced out. The visual record we should be looking at includes the printed laws and the letters written in the Sequoyah syllabary.

Actionable Steps for Genuine Research

If you want to truly see the Trail of Tears, stop looking for "photos" and start looking for the following primary sources:

- The National Archives: Search for "Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs." You can see the actual muster rolls—the lists of names of people who were forced onto the boats and wagons.

- The Trail of Tears Association (TOTA): They have mapped the actual routes. You can visit the physical locations, like Mantle Rock in Kentucky or Berry’s Ferry. Seeing the physical geography is more revealing than any mislabeled photo.

- Tribal Museums: Visit the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. They have life-cast sculptures and exhibits that are based on actual historical descriptions, not Hollywood tropes.

- The "Cherokee Phoenix" Archives: Read the digitized newspapers from 1828. Seeing the words of the people who were about to be removed provides a "snapshot" of their minds that a camera never could have captured.

The real story of the Trail of Tears isn't found in a grainy JPEG from 1890. It’s found in the persistence of the nations that still exist today. Next time you see a "photo" of the trail, look a little closer at the date. Usually, the real story is much more complicated—and much more interesting—than the fake image suggests.