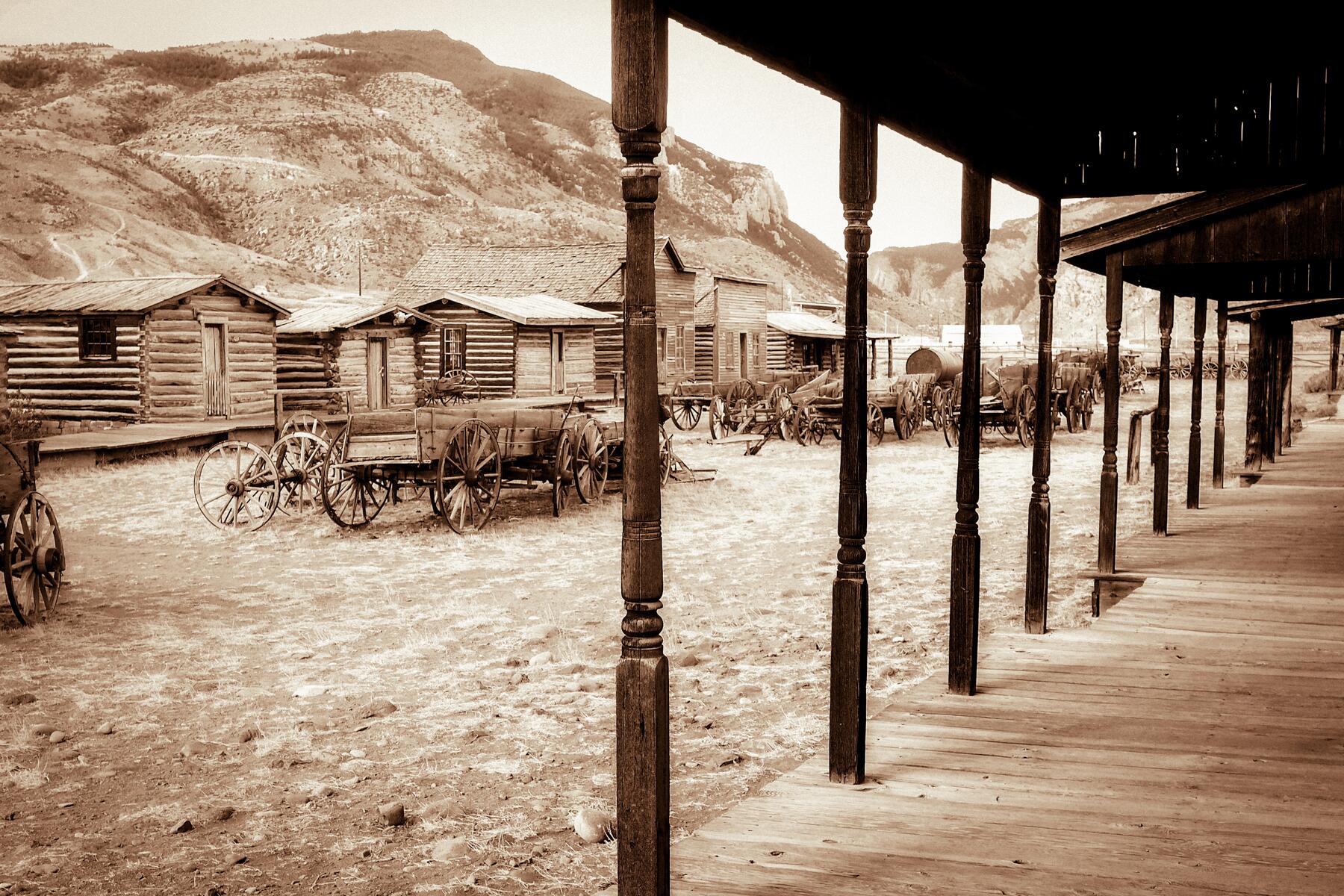

The camera doesn't lie, but it definitely used to squint. When you look at photos of old western towns from the late 1800s, there is this immediate, jarring realization that Hollywood basically lied to us for seventy years. Dirt. It’s everywhere. In the real photos—the ones tucked away in the Library of Congress or the University of Nevada’s digital archives—the streets aren't just dusty. They are churned-up mires of horse manure and wagon-wheel ruts that look deep enough to swallow a toddler.

You’ve seen the movies. The cowboy rides into a pristine, sun-bleached town with neatly painted boardwalks.

Reality was way messier.

The Grainy Truth in Photos of Old Western Towns

Most of what we know about places like Tombstone, Virginia City, or Bodie comes from the massive glass-plate negatives of photographers like Timothy O'Sullivan or Carleton Watkins. These guys weren't trying to make "art." They were documenting reality for a curious East Coast audience.

Wait.

Look closer at a shot of Main Street in Eureka, Utah, circa 1885. The first thing you notice isn't the saloons. It's the sheer lack of trees. In their rush to build "civilization," settlers clear-cut everything. These towns looked like scars on the landscape. They were brown, gray, and stark. Because the film of the era—usually orthochromatic—wasn't sensitive to red light, skin tones looked weathered and skies often appeared as a blank, haunting white. It gives these photos of old western towns a ghostly, apocalyptic vibe that feels more like The Road than Bonanza.

The "False Front" Architecture Trick

Ever wonder why every building looks two stories tall in photos but looks like a shack from the side? That’s the "Boomtown Front."

💡 You might also like: Weather in Lexington Park: What Most People Get Wrong

It was basically 19th-century catfishing.

Store owners built tall, squared-off facades onto simple peaked-roof cabins to make the town look more "established" to potential investors. If you find a side-angle photo of a place like Leadville, Colorado, you can see the hustle. The front is a proud, ornate Victorian face; the back is a rough-hewn log pile. It was all about the optics. They were desperate to prove they weren't just a camp, but a city.

Why Some Towns Survived and Others Just Vanished

It usually came down to the "Second Act."

A lot of the photos of old western towns we see today are actually photos of ghost towns—places that died the second the silver or gold ran out. Bodie, California, is the gold standard for this. If you visit today, or look at the high-res archival shots from the 1960s versus the 1880s, you see "arrested decay." The California State Parks system keeps it exactly as it was when the last residents packed up.

But then you have the survivors.

Places like Deadwood or Telluride didn't stay "Western." They evolved. Telluride went from a gritty mining camp where Butch Cassidy robbed his first bank to a high-end ski resort. In those early photos of old western towns, Telluride looks terrifying. It's a cramped canyon filled with coal smoke and grit. Today, it's a postcard. The transition is usually visible in the shift from wood to brick. After the inevitable "Great Fire" that burned down almost every wooden Western town at least once, the survivors rebuilt with masonry. If the photos show brick buildings, that town had money. If it’s all wood, it was probably gone by the next census.

📖 Related: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

The People Behind the Lens

We have to talk about Andrew J. Russell. He was one of the few who captured the "work" of the West. His photos of the Union Pacific Railroad construction show the brutal reality of these towns. They weren't just places to live; they were machines for extraction.

You see the laborers. You see the Chinese immigrants who built the backbone of the West but were often cropped out of the "official" celebratory photos. When you dig into the unedited archives, the diversity of these towns hits you. It wasn't just white guys in hats. It was a melting pot of people from across the globe, all covered in the same layer of alkaline dust.

How to Spot a Fake or "Staged" Historical Photo

Authenticity is a tricky beast. By the 1890s, the "Wild West" was already becoming a brand. Buffalo Bill Cody was touring, and people started "playing" cowboy for the camera.

If you’re looking at photos of old western towns and everyone looks perfectly posed with their guns drawn, it’s probably a studio shot or a later reenactment. Real candids are rare because shutter speeds were slow. People had to stand still. That’s why you rarely see people smiling; it’s hard to hold a grin for five seconds without looking like a maniac.

- Check the shadows. If they are harsh and vertical, it's a real outdoor shot.

- Look at the ground. Real towns had trash. Tin cans, broken glass, and manure are the hallmarks of a genuine 19th-century street.

- Observe the clothing. Real miners didn't wear "costumes." They wore layers of heavy wool and canvas that were stained with sweat and minerals.

Finding the Best Public Archives

You don't need to buy expensive books to see the real stuff. Most of the best imagery is sitting in public servers.

The Library of Congress has the "Chronicling America" project. It is a rabbit hole. You can find photos of towns that don't even have a name on a modern map. Then there’s the Denver Public Library’s Western History Collection. They have digitized thousands of plates that show the transition from tepees to telegraph lines.

👉 See also: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

Honestly, the best way to spend an afternoon is searching these databases for "General Store interior." The sheer amount of stuff crammed into those wood-frame buildings is mind-blowing. It wasn't just a shop; it was the town's lungs.

Practical Steps for Researching Old West Photography

If you are trying to track down the history of a specific place or just want to build a collection of authentic imagery, stop looking at Pinterest. It’s a graveyard of mislabeled AI-generated "old" photos.

Step 1: Use Sanborn Maps. If you find a photo of a town but don't know where the camera was standing, look up the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps for that year. They are incredibly detailed layouts of every building in almost every American town. You can cross-reference the shape of a roof in a photo with the map to find the exact street corner.

Step 2: Check the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) Digital Collections. They have a specific focus on the Southwest and the "lure" of the desert. Their collection of photos of old western towns includes a lot of the smaller, fringe settlements that didn't make it into the history books.

Step 3: Verify the Photographer. Research names like F. Jay Haynes or Solomon Butcher. Butcher, specifically, documented the sod-house era in Nebraska. His photos are weirdly intimate. He often had families bring all their furniture out into the yard so they could show off their possessions in one single shot. It’s the 1880 version of a "flex."

Step 4: Visit a "Living" Ghost Town. Go to St. Elmo, Colorado, or Bannack, Montana. Take your own photos. Compare the topography of the mountains in your shots to the historical ones. The buildings change, but the ridgeline of the Rockies stays the same. It’s the only way to truly ground yourself in the scale of what those settlers were dealing with.

The real West wasn't a movie set. It was a loud, smelly, precarious experiment in survival, and the photos are the only evidence we have left of the grit before it was polished by Hollywood.