You’ve seen them. Those glowing, purple-and-gold ribbons stretching across a pitch-black sky. They look like something out of a Marvel movie, right? Honestly, the first time I saw a high-end photo of the Milky Way galaxy from Earth, I thought it was fake. I figured someone just got really aggressive with the saturation slider in Photoshop and called it a day.

But it’s real. Mostly.

The disconnect happens because your eyes are basically garbage at seeing color in the dark. We evolved to spot predators in the grass, not to pick up the faint ionization of hydrogen gas millions of light-years away. When you stand in a "dark sky" park, you see a faint, cloudy smear. It's cool, sure, but it isn't the neon dreamscape you see on Instagram.

Capturing photos of the Milky Way galaxy from Earth is a weird mix of high-end physics, expensive glass, and a whole lot of patience in the cold. It’s about hacking the way light works to see what our biological hardware simply can't.

The Galactic Center and the "Season" Problem

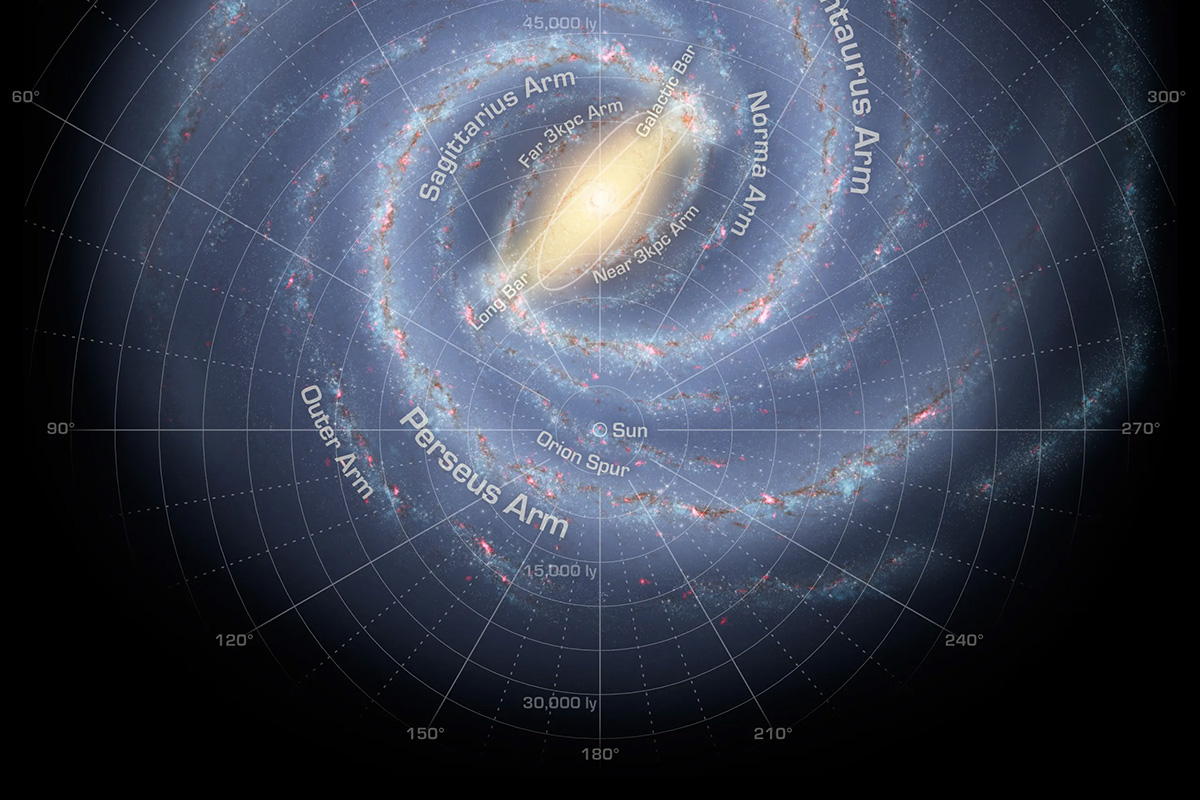

You can’t just walk outside on any random night and expect to see the core. The Earth is inside the galaxy, which is a flat disk. Think of it like being a tiny speck of dust trapped inside a giant pepperoni pizza. Depending on which way you’re looking, you’re either looking toward the thick, cheesy center or out toward the thin crust.

The "Galactic Center"—the part with all the dramatic dust lanes and bright stars—is only visible during "Milky Way Season." In the Northern Hemisphere, that’s roughly March through October. If you try to take photos in December, you're looking the wrong way. You’re looking out at the edge of the pizza. It’s still pretty, but it’s not the show-stopper people want.

Location is everything. If you’re within 50 miles of a major city, forget it. Light pollution is the ultimate enemy here. Astronomers use something called the Bortle Scale to measure darkness. A Bortle 1 or 2 site is the holy grail. That’s where the sky is so dark the stars actually cast a shadow on the ground. Places like the Atacama Desert in Chile or the Mauna Kea observatory in Hawaii are legendary for this, but you can find "Dark Sky" spots in places like Utah or West Virginia too.

🔗 Read more: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

How Cameras Cheat (Legally)

Your eye refreshes its "image" about every 1/60th of a second. A camera doesn't have to do that. To get those stunning photos of the Milky Way galaxy from Earth, photographers leave the shutter open for 15, 20, or even 30 seconds.

This is called a long exposure.

In those 20 seconds, the camera sensor gathers thousands of times more light than your eye ever could. It drinks in the photons. That’s how we see the pinks and cyans of distant nebulae. But there’s a catch: the Earth is spinning.

If you leave your shutter open too long, the stars turn into little white streaks. It’s called "trailing." To fix this, photographers use the Rule of 500. Basically, you take 500 and divide it by the focal length of your lens to find the maximum number of seconds you can shoot before things get blurry. Or, if you’re a pro, you use an equatorial mount—a motorized tripod that rotates at the exact same speed as the Earth, effectively "freezing" the stars in place.

The Post-Processing Truth

Let’s be real for a second. No photo comes out of the camera looking like a masterpiece. Raw files are flat, gray, and depressing.

Processing a Milky Way photo isn't about "faking" it; it's about bringing out the data that’s already there. Because the light is so faint, the "signal-to-noise ratio" is a mess. You get a lot of "grain" or "noise" that looks like colorful static.

💡 You might also like: Brain Machine Interface: What Most People Get Wrong About Merging With Computers

To combat this, photographers use a technique called stacking. They’ll take 10 or 20 identical photos of the same patch of sky and use software like Starry Landscape Stacker or Sequator to average them out. This cancels out the random noise and leaves behind the pure, crisp light of the stars.

Then comes the "stretching." This is where you adjust the histogram to make the dark sky darker and the bright stars pop. This is where the colors come to life. Those magentas and deep blues? They aren't added in. They are the actual colors of gasses like Hydrogen-alpha, which our eyes perceive as gray in the dark because our "cones" (the color sensors in our eyes) shut down in low light, leaving only our "rods" (which only see black and white).

Why the Foreground Matters

A photo of just stars is a science diagram. A photo of the Milky Way over a jagged mountain range or a lone pine tree is art. This is the hardest part of the hobby.

Usually, the sky and the ground require different settings. If you expose for the stars, the ground is a black silhouette. If you want detail in the rocks, you have to take a separate, much longer exposure (sometimes several minutes) and blend them together in Photoshop. This is a "composite," and while some purists hate it, it’s the only way to replicate how a human feels standing in that landscape.

Gear Check: What You Actually Need

You don’t need a $10,000 rig, but a smartphone usually won't cut it for "professional" results (though the latest flagship phones are getting scarily good with "Night Mode").

- A Wide Lens: You want a 14mm to 24mm lens. The wider the better, so you can capture the "arch" of the galaxy.

- Fast Aperture: Look for a lens with an f-stop of f/2.8 or lower. This is the "bucket" that catches the light.

- A Sturdy Tripod: Even a tiny vibration from the wind will ruin a 20-second shot.

- A Remote Shutter: Even the act of pressing the button can shake the camera. Use a 2-second timer instead.

Misconceptions and the "Fake" Allegations

One of the biggest complaints people have is, "I went to the spot in the photo and it didn't look like that!"

📖 Related: Spectrum Jacksonville North Carolina: What You’re Actually Getting

That’s fair. But it’s not a lie.

Photography is the art of capturing time. A photo of the Milky Way is a 30-second summary of a moment. Our eyes only experience the "now." The camera experiences the "duration." Both are "real" versions of the truth, they just use different scales.

Also, those "rainbow" Milky Ways? Sometimes those are a bit exaggerated. Some photographers crank the "vibrance" until it looks like a bag of Skittles exploded in space. It’s a stylistic choice, but it’s why it’s important to look at work from organizations like the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) to see what natural, responsible astrophotography looks like.

How to Get Your Own Shot

If you want to start taking photos of the Milky Way galaxy from Earth, don't just wing it.

- Check the Moon Phase: You want a New Moon. A full moon is so bright it’ll wash out the stars. It’s basically a giant natural streetlamp.

- Use an App: Use PhotoPills or Stellarium. These apps use AR to show you exactly where the Milky Way will be at 3:00 AM before you even leave your house.

- Focus Manually: Your camera’s autofocus will fail in the dark. Turn it to manual, use "Live View" to zoom in on a single bright star, and twist the focus ring until that star is a tiny, sharp needlepoint.

- Shoot in RAW: Never shoot JPEGs for stars. You need the raw data to fix the white balance and pull detail out of the shadows later.

Next Steps for Aspiring Astrophotographers

Stop looking at the screen and start planning. Find a "Dark Sky Map" online and look for the nearest "Green" or "Blue" zone near you. Pack a headlamp with a red light mode (red light doesn't ruin your night vision like white light does).

Start with the gear you have. Even an entry-level DSLR with a kit lens can capture the Great Rift of the Milky Way if the sky is dark enough. The most important "gear" is actually your location and the timing of the moon. Get those two right, and the rest is just clicking a button and waiting in the dark.