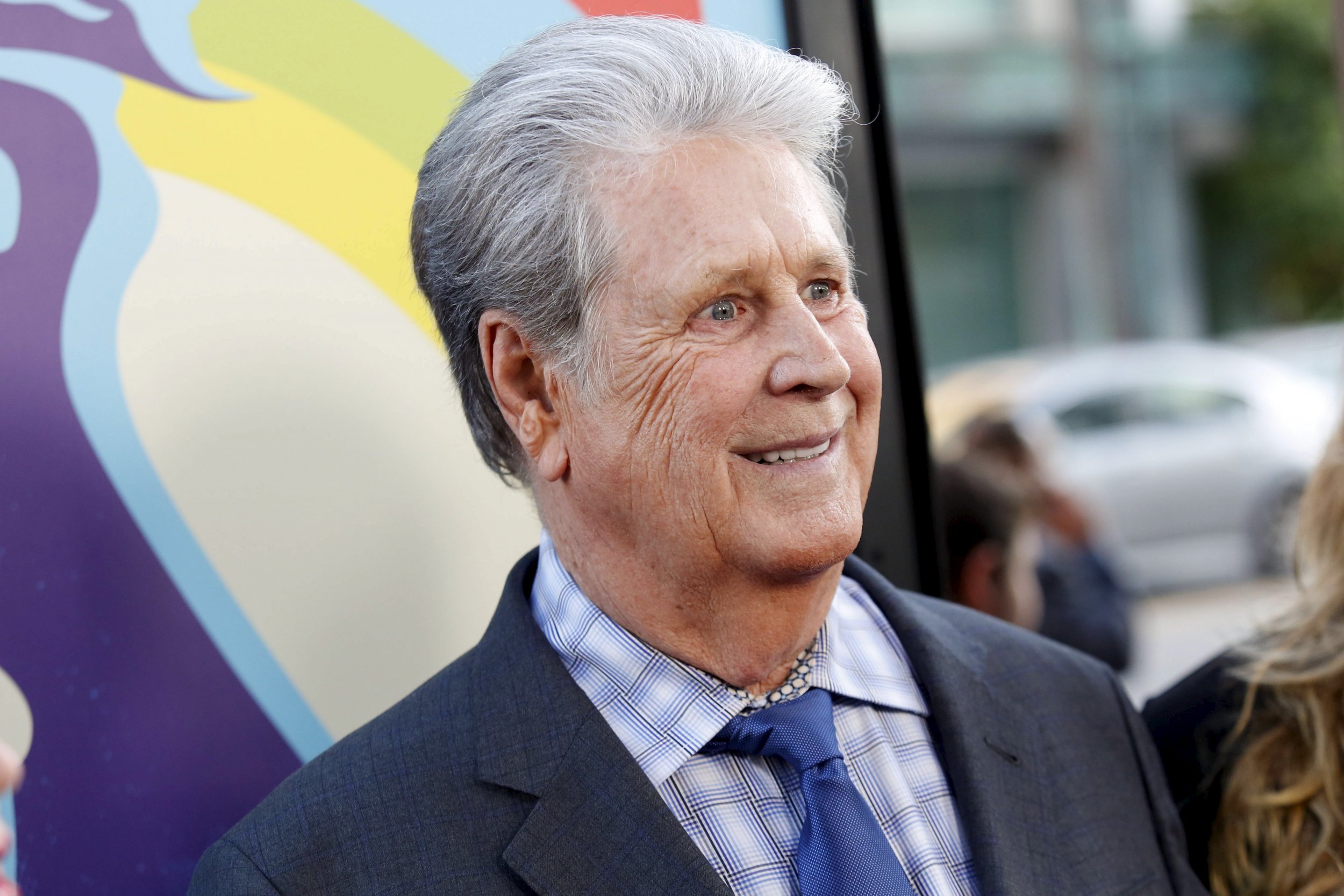

Brian Wilson was twenty-three years old when he sat down at a piano in 1965 and decided to destroy the concept of a "pop song." He wasn't trying to be an intellectual. He wasn't trying to start a revolution. Honestly? He was just terrified of the Beatles.

When Rubber Soul hit the shelves, Brian heard it and basically panicked. Up until then, albums were just a couple of hits padded out with filler—cheap covers and throwaway tracks. The Beatles changed the rules. Brian realized he couldn't just write about surfing and hot rods anymore. He needed to make the "greatest rock album ever made." That obsession birthed Pet Sounds, a record that exists in its own weird, lonely, beautiful universe.

It’s easy to look back now and call it a masterpiece. Everyone does. But at the time? Capitol Records thought he’d lost his mind. They hated it. They didn't know what to do with a record that featured bicycle horns, barking dogs, and lyrics about a young man feeling like he didn't belong in his own skin.

The Sound of One Man Losing His Grip

The making of Pet Sounds and Brian Wilson's subsequent descent into perfectionism is the stuff of legend. You’ve probably heard about the sandbox under the piano or the way he made the Wrecking Crew—the elite session musicians of LA—play the same four bars for three hours straight. He wasn't just looking for a "good" take. He was chasing a specific frequency that lived inside his head.

Brian used the studio as an instrument. Think about that for a second. In 1966, most bands walked in, plugged in, and played. Brian didn't. He used theremins. He used water bottles. He used harpsichords. On the track "You Still Believe in Me," he actually had someone reach inside a piano and pluck the strings directly to get that delicate, chime-like sound.

It was expensive. It was slow. It was exhausting.

The other Beach Boys weren't exactly thrilled when they got back from touring Japan and found out their resident genius had replaced their guitars with a symphony of "found sounds." Mike Love famously clashed with Brian over the direction. He wanted hits. He wanted the formula. Brian wanted "God Only Knows."

📖 Related: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Why God Only Knows Changed Everything

If you want to understand why Pet Sounds matters, you have to look at "God Only Knows." Paul McCartney famously called it the greatest song ever written. It starts with a French horn. A French horn! In a pop song.

The chord progression is essentially a mathematical miracle. It never quite feels like it lands on solid ground until the very end. It’s "tonally unstable," as musicologists like to say. That’s why it feels like yearning. It mimics the feeling of being unsure of your place in the world.

"I would wake up and wonder if I was going to be able to make it through the day." — Brian Wilson, reflecting on the mid-sixties.

That vulnerability is why the record survives. It’s not just the technical brilliance. It’s the fact that Brian Wilson was a superstar who was brave enough to admit he was scared. While other bands were singing about revolution or drugs or girls, Brian was singing "I just wasn't made for these times."

The Wrecking Crew and the Wall of Sound

Brian was obsessed with Phil Spector. He wanted to out-Spector Spector. He took the "Wall of Sound" concept—layering dozens of instruments to create a dense, mono wash—and added a level of sophistication that Spector never touched.

He didn't use the Beach Boys for the instruments on Pet Sounds. He used the best session players in the world. Carol Kaye, the legendary bassist, talked about how Brian would have her play lines that didn't make sense to her at first. They were counter-melodies. They were weird. But when you heard the whole mix? It was magic.

👉 See also: Carrie Bradshaw apt NYC: Why Fans Still Flock to Perry Street

The complexity of the arrangements is staggering. Take "Sloop John B." It started as a folk song Al Jardine suggested. Brian turned it into a massive, multi-tracked production that sounds like a technicolor dream. The vocals are stacked so deep it’s hard to tell where one voice ends and the next begins.

The Tragic Aftermath of Brilliance

Here is the part most people get wrong: they think Pet Sounds was an instant smash. It wasn't. Not in America.

In the UK, it was a massive hit. The "cool" kids got it. The Beatles got it. Eric Clapton got it. But back home? It stalled. Capitol Records actually released a "Best Of" album shortly after to recoup the money they thought they’d lost. Imagine being Brian Wilson, pouring your entire soul, your mental health, and your artistic integrity into a project, only for your label to basically say, "Cool, but where’s 'California Girls 2'?"

That rejection broke something in him. It led directly into the Smile sessions, the famous "nervous breakdown," and decades of struggle.

The irony is that Pet Sounds and Brian Wilson are now inseparable from the definition of "prestige pop." You can hear its DNA in everything from Radiohead to Fleet Foxes to Taylor Swift’s more experimental arrangements. It taught the world that a pop album could be a cohesive piece of art, a "symphonic" experience rather than a collection of singles.

The Technical Wizardry You Might Miss

If you listen to the album on headphones today, try to focus on the percussion. It’s bizarre. There are sleigh bells everywhere. There are timpani rolls.

✨ Don't miss: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

- "Caroline, No" uses the sound of a passing train.

- "Pet Sounds" (the instrumental track) features empty Coca-Cola cans being hit with drumsticks.

- The transition between songs was planned with the precision of a classical suite.

Brian was doing "sampling" before samples existed. He was cutting tape and splicing it together to create sounds that couldn't exist in nature. He was a pioneer of the recording studio as a laboratory.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Listener

To truly appreciate what happened in those sessions, you can’t just listen to it on a tiny phone speaker while doing dishes. You need to engage with it the way Brian intended.

1. Listen to the Mono Mix First

Brian Wilson is deaf in one ear. He didn't care about stereo. He wanted the "punch" of mono. The stereo mixes are interesting, but the mono version is the one Brian actually produced and authorized. It’s the "real" experience.

2. Watch "Love & Mercy"

If you haven't seen the 2014 biopic, do it. Paul Dano’s portrayal of Brian during the Pet Sounds era is hauntingly accurate. It captures the frantic, joyful, and ultimately terrifying process of a man trying to capture "the music of the spheres" while his mind begins to fray.

3. Analyze the Lyrics of Tony Asher

Brian didn't write the lyrics alone. He worked with Tony Asher, an advertising copywriter. They spent hours talking about their feelings, their breakups, and their insecurities. Notice how the lyrics aren't "cool." They are almost painfully earnest. That’s the secret sauce.

4. Compare it to "Revolver"

Listen to Pet Sounds, then listen to the Beatles' Revolver (released the same year). You can hear the conversation between the two bands. It was an arms race of creativity that pushed the entire genre of music forward by a decade in just twelve months.

Brian Wilson eventually found a version of peace. He finished Smile decades later. He toured. He saw his masterpiece finally recognized as one of the greatest achievements in human creativity. But the cost was immense. Pet Sounds remains a beautiful, fragile monument to what happens when a human being tries to be perfect in an imperfect world. It’s a record that sounds like a sunset—gorgeous, but with the haunting realization that the light is about to go out.

Go back and listen to "I'm Waiting for the Day." Listen to the way the drums explode. Listen to the hurt in Brian’s voice. It’s still there, sixty years later, just as raw as the day he cut the tape.