Honestly, when people think of Tennessee Williams, they usually picture Vivien Leigh screaming for Stella or Paul Newman brooding in a silk robe. It’s all sweat, Southern gothic melodrama, and tragic endings. But then there’s Period of Adjustment, a weirdly charming, often overlooked 1962 film that feels like it wandered off the wrong set and into a romantic comedy. It is the only "serious" comedy Williams ever wrote, and the movie version is a fascinating time capsule of 1960s anxiety.

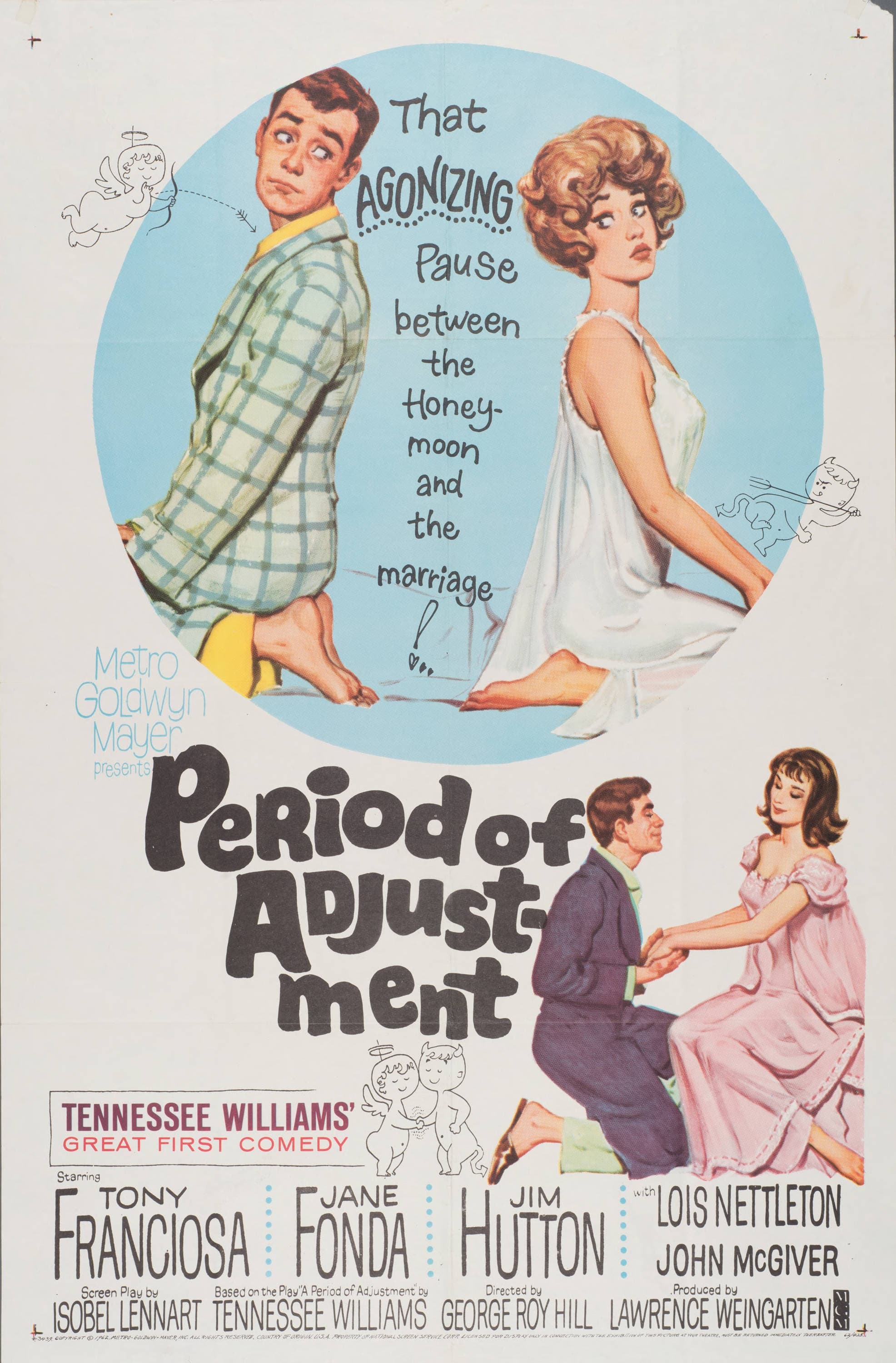

Directed by George Roy Hill—the guy who later gave us Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid—this film doesn't get the same flowers as A Streetcar Named Desire. It should. It’s got a young Jane Fonda, a very tense Jim Hutton, and a plot that basically revolves around two couples having a collective nervous breakdown on Christmas Eve.

The Messy Reality of Period of Adjustment

The movie kicks off with George Haverstick (Hutton) and Isabel (Fonda). They just got married. They should be happy. Instead, George has a psychosomatic "the shakes" from his time in the Korean War, and Isabel is realizing her husband is basically a stranger who bought a giant, hideous Cadillac hearse for their honeymoon.

They end up at the home of George’s war buddy, Ralph Baitz (played by Anthony Franciosa). If they were looking for stability, they picked the wrong house. Ralph’s wife, Dorothea, just walked out on him because he quit his job at her father’s company. It’s a pressure cooker. You’ve got one couple who can’t figure out how to start a life together and another whose life is imploding in real-time.

What makes Period of Adjustment stand out is how it handles masculinity. In 1962, movies weren't exactly rushing to show war veterans trembling with anxiety or admitting they were scared of intimacy. Williams, through the screenplay adapted by Isobel Lennart, strips away the bravado. George isn't a hero; he's a guy who can't keep his hands from shaking. Ralph isn't a success; he’s a man who hates that his dignity is tied to his father-in-law’s paycheck.

Jane Fonda’s Early Spark

This was only Fonda’s fourth film. You can see the movie star DNA already working. She plays Isabel with this frantic, high-pitched desperation that is both annoying and incredibly sympathetic. She’s a nurse who thought marriage was a cure-all, only to find herself stuck in a literal hearse in a snowstorm.

👉 See also: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

The chemistry between her and Hutton is deliberately awkward. It’s supposed to be. They are two people who barely know each other trying to navigate the "period of adjustment" that every marriage supposedly goes through. The term itself is treated like a joke throughout the film—a phrase people use to hand-wave away genuine psychological trauma.

Why Modern Audiences Are Rediscovering the Film

Most people find this movie because they are completing a Tennessee Williams checklist. They stay because it’s surprisingly relatable. While the gender roles are definitely dated—Dorothea is often criticized for her looks in a way that feels cruel today—the core themes of economic stress and "keeping up with the Joneses" hit hard.

Subverting the Christmas Movie Trope

It’s technically a Christmas movie. There’s a tree. There are gifts. There’s even a suburban neighborhood that looks like a postcard. But the film uses the holiday as a blunt instrument. Christmas is the deadline for happiness. If you aren't happy by the time the carols start, you’ve failed.

Ralph’s house is built over a cavern. This is a classic Williams metaphor. The suburban dream is literally sinking into a hole in the ground. You’ve got these beautiful mid-century interiors, but the walls are cracking because the foundation is garbage. If that isn't a metaphor for the 1950s American dream curdling into the 1960s, nothing is.

Production Secrets and Behind-the-Scenes Friction

George Roy Hill wasn't the first choice for everyone, but he brought a certain lightness that prevented the movie from becoming too grim. This was his directorial debut in feature films. He had come from "Playhouse 90" and other TV heavyweights, and you can see that background in the way he handles the tight, interior spaces of Ralph’s sinking house.

✨ Don't miss: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

The film was shot at MGM, and they leaned heavily into the "New Star" marketing for Fonda and Hutton. They had previously starred together in The Tall Story, and the studio was desperate to make them the next "It" couple.

- The Screenplay: Isobel Lennart (who wrote Funny Girl) did the adaptation. She kept Williams' bite but smoothed out some of the more jagged edges of the play.

- The Score: Lyn Murray provided a soundtrack that bounces between jaunty and melancholy, perfectly mimicking George’s mood swings.

- The Critical Reception: At the time, critics were mixed. They didn't know what to do with a "funny" Tennessee Williams. The New York Times called it "a surprisingly funny and lighthearted comedy," which almost sounds like an insult when applied to a writer known for lobotomies and cannibalism.

The "Sinking House" Metaphor Explained

Let’s talk about that house. The Baitz residence is located in a development called "High Point," which is ironic because everyone is at their lowest point. The fact that the house is physically tilting is the most "on the nose" thing Williams ever wrote, but in the film, it works.

As the night goes on and the characters get drunker, the physical instability of the set mirrors their emotional states. When Ralph explains to George that the whole neighborhood is built on a fault line, he isn't just talking about geology. He’s talking about the middle-class expectation of "having it all." You get the wife, the house, the job, and then you realize you’re standing on hollow ground.

Comparing the Play to the Film

If you’ve read the 1960 play, you’ll notice the movie is a bit softer. Williams originally wrote the play as a "serious comedy," but the Broadway version had a bit more of that raw, visceral pain he’s famous for.

The movie focuses more on the comedic misunderstandings. Jim Hutton’s performance is very physical—lots of twitching and stumbling. In the play, George’s tremors feel more like a symptom of PTSD (though they didn't call it that then). In the movie, it's played slightly more for laughs, which is a bit of a 1962 era-specific choice that might grate on modern viewers.

🔗 Read more: Why Grand Funk’s Bad Time is Secretly the Best Pop Song of the 1970s

However, the ending remains one of the most optimistic in the Williams canon. Usually, his characters end up in mental institutions or dead. Here, there’s a glimmer of hope. Not a "happily ever after," but a "maybe we can make this work if we stop lying to ourselves."

Practical Takeaways for Film Buffs

If you’re planning to watch Period of Adjustment, go into it expecting a character study rather than a plot-driven rom-com. It’s a talky movie. It’s a play on film.

Where to watch: It’s often available on Turner Classic Movies (TCM) or for digital rental on platforms like Amazon and Apple. It’s rarely on the "big" streamers like Netflix, so you have to hunt for it.

What to look for: Watch Jane Fonda’s eyes. She does a lot of heavy lifting in scenes where she has no dialogue. Also, pay attention to the set design. The "tilting" of the house is subtle at first but becomes more pronounced as the domestic arguments escalate.

Context is key: Remember that this came out just as the sexual revolution was starting to simmer. The anxieties about "marital duties" and "manhood" are very much of their time, but the underlying fear of being alone is universal.

To truly appreciate the film, watch it as a double feature with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. You’ll see how Williams recycled his favorite themes—deceit, liquor, and the crushing weight of family expectations—but found a way to let his characters breathe for once. It’s not his "best" work in a traditional sense, but it is perhaps his most human.

To explore this era of cinema further, start by tracking the transition of Broadway plays to MGM features in the early 60s. Look specifically at the work of Isobel Lennart to see how she translated difficult stage material for a mass audience. If you want to see Fonda's evolution, compare her performance here to her work just seven years later in They Shoot Horses, Don't They?—the difference is staggering. For a deep dive into the technical side, research George Roy Hill's use of deep focus in interior sets to create a sense of claustrophobia without losing the comedic timing of his actors.