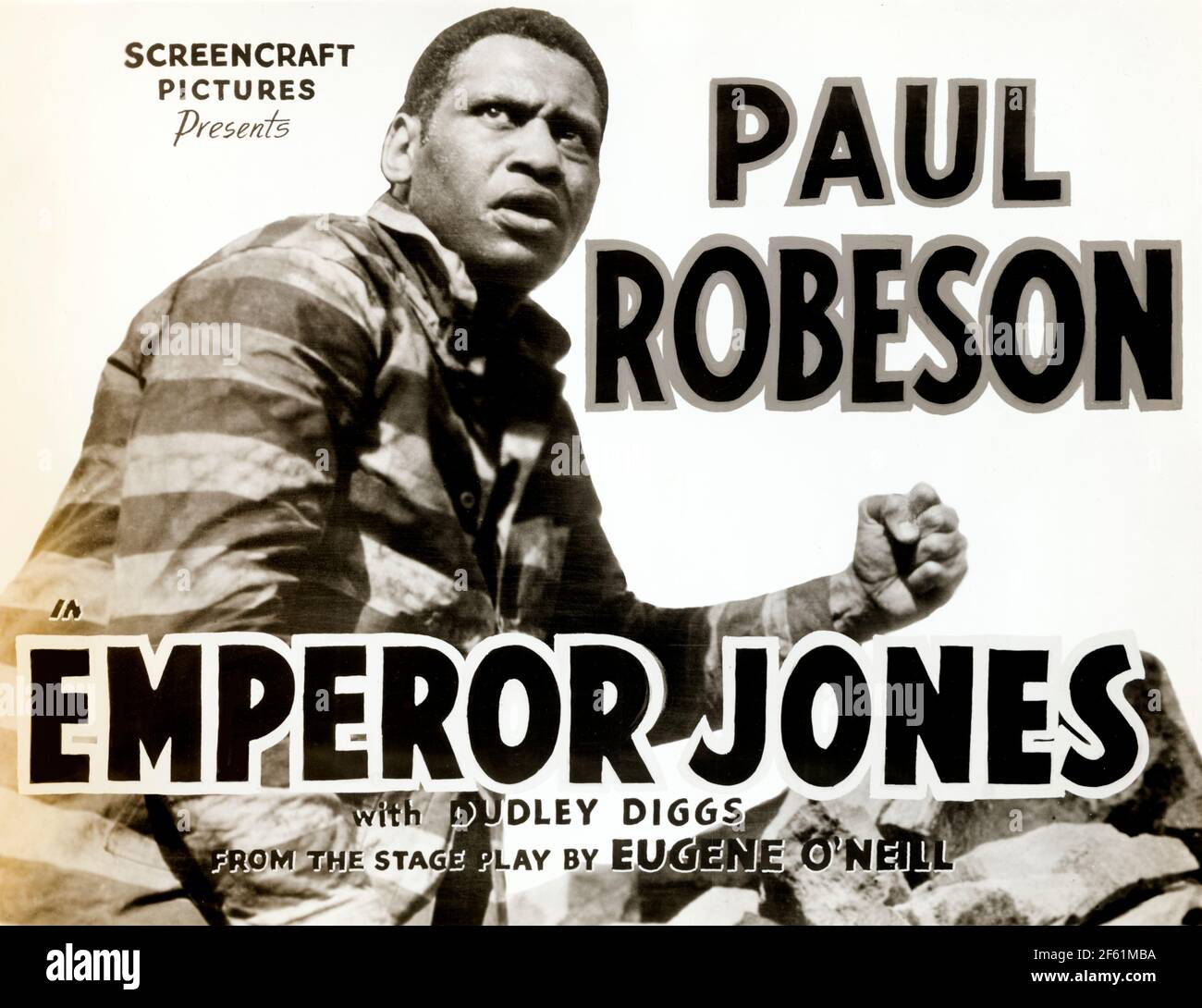

Honestly, if you look back at the 1930s, the idea of a Black man commanding a major motion picture wasn't just rare—it was practically nonexistent. Then came Paul Robeson in The Emperor Jones. He didn't just walk onto the screen; he took it over.

You’ve got to understand the climate of 1933. Hollywood was busy churning out "Sambo" caricatures and subservient maids. Along comes Robeson, a man with a law degree from Columbia and the physique of an All-American football player, playing Brutus Jones. Jones isn't a saint. He’s a killer, a con artist, and a self-appointed dictator. But he was the lead.

It changed everything.

The Performance That Broke the Rules

The story follows Brutus Jones, a Pullman porter who kills a man over a craps game, escapes a chain gang, and somehow maneuvers himself into becoming the "Emperor" of a Caribbean island. It sounds like a fever dream. For Robeson, it was a vehicle to showcase a kind of Black masculinity that white audiences had never seen—and frankly, were terrified of.

👉 See also: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

One of the most jarring things for viewers back then was seeing Robeson’s character being served by a white man. Henry Smithers, the Cockney trader played by Dudley Digges, becomes Jones's subordinate. Seeing a Black man give orders to a white man on a movie screen in 1933? It was like an atom bomb went off in the theater.

Robeson’s voice helped. That deep, resonant bass-baritone didn't just deliver lines; it rattled the floorboards. When he sings "Water Boy" in the prison scene, you aren't just watching a movie. You’re witnessing a piece of American history that feels heavy, raw, and uncomfortably real.

Why Paul Robeson in The Emperor Jones is so Complicated

If you watch it today, you’re going to cringe. Let’s be real. The film is peppered with the n-word and relies on "jungle" motifs that feel incredibly dated. Scholars like Michael C. Reiff have pointed out that while the film was groundbreaking, it still suggested that beneath the "civilized" exterior of Brutus Jones lay a "primitive brute."

✨ Don't miss: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

The second half of the movie is basically a long descent into madness. As Jones flees through the jungle, he hallucinates. He loses his fine clothes piece by piece until he's nearly naked, haunted by the "ghosts" of his past and his race.

Robeson himself had a bit of a love-hate relationship with the project. He knew it was a "step up" from the usual trash offered to Black actors, but he later expressed regret over the liberties taken with Eugene O’Neill’s original script. He felt the film leaned too hard into stereotypes he was trying to dismantle.

The Friction Between the Play and the Film

- The Backstory: The 1933 film actually adds a massive chunk of backstory that wasn't in O’Neill’s 1920 play.

- The Tone: The play is more of an expressionist nightmare; the movie tries to be a realistic rise-and-fall drama.

- The Controversy: Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) hated the film. They felt it mocked Black leadership and the ritualism of Pan-African movements.

It’s easy to judge the film through a 2026 lens, but that misses the point of why Paul Robeson in The Emperor Jones was such a radical act. Robeson took a role that was written with "primitive" undertones and filled it with so much intelligence and "bottomless charisma" (as critics at the University of Albany put it) that the stereotypes started to crack.

🔗 Read more: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The Legacy of a Silver Bullet

The "Emperor" believes only a silver bullet can kill him. It’s a metaphor for his own arrogance, sure, but it also speaks to the mythic quality Robeson brought to the role. He wasn't just playing a character; he was building the blueprint for the Black leading man.

Without this performance, do we get Sidney Poitier? Do we get Denzel?

The film was an independent production because no major studio would touch it. They were scared of the Southern box office. They were scared of "miscegenation" (producers even made actress Fredi Washington wear dark makeup because she looked "too white" next to Robeson). Yet, it survived.

Actionable Insights: How to Approach This Classic

If you're looking to dive into this era of cinema or understand Robeson’s impact, don't just read about it. Experience the nuance for yourself:

- Watch the Criterion Restoration: Don't settle for the grainy, public-domain versions on YouTube. The Library of Congress restoration preserves the original lighting and sound that make Robeson's performance so haunting.

- Compare the "Ol' Man River" Transformation: Watch his performance here and then watch him in Show Boat (1936). You'll see how he began to use his fame to demand changes in lyrics and scripts to reflect Black dignity.

- Read "Here I Stand": This is Robeson's autobiography. It provides the necessary context for his later blacklisting by the HUAC and why his "Emperor" role was just the start of his political defiance.

The film is a paradox. It is both a masterpiece of early Black cinema and a relic of a deeply racist era. But at the center of it is Paul Robeson, a man who was always too big for the boxes the world tried to put him in. He didn't just play the Emperor; for a brief moment in 1933, he actually was one.