Believe. You gotta believe.

If you grew up in the late nineties, those four words weren't just a catchphrase; they were a mantra for a generation of PlayStation owners trying to figure out how a paper-thin dog in a beanie could teach them the meaning of life. Parappa the Rapper games didn't just invent the modern rhythm genre; they did it with a specific kind of weirdness that developers today are still desperately trying to replicate.

Sony took a massive gamble in 1996. Before Guitar Hero or Rock Band were even glimmers in a developer's eye, Masaya Matsuura and artist Rodney Greenblat teamed up to create something that looked like a child’s pop-up book but sounded like a funky 90s hip-hop mixtape. It shouldn't have worked. A rapping dog trying to get his driver's license? An onion-headed sensei teaching karate in a flea market? It sounds like a fever dream. Yet, it became the cornerstone of a cult-classic franchise that changed everything.

📖 Related: ARK: Survival Evolved Explorer Notes The Island Locations and the Lore You’re Probably Missing

The Design Philosophy That Broke the Rules

Most rhythm games today are about perfection. You see a note, you hit the note, you get a "Perfect" or "Great" rating. It’s clinical. It's basically a typing test set to music. But the original Parappa the Rapper games were never really about being a metronome.

Matsuura-san, the founder of NanaOn-Sha, was a musician first. He wanted players to feel the "groove." This is why, if you go back and play the original PS1 disc today, the timing feels... off. It's notoriously "crunchy." If you hit the buttons exactly on the beat, the game often tells you that you're failing. It wants you to lead the beat slightly. It wants you to freestyle.

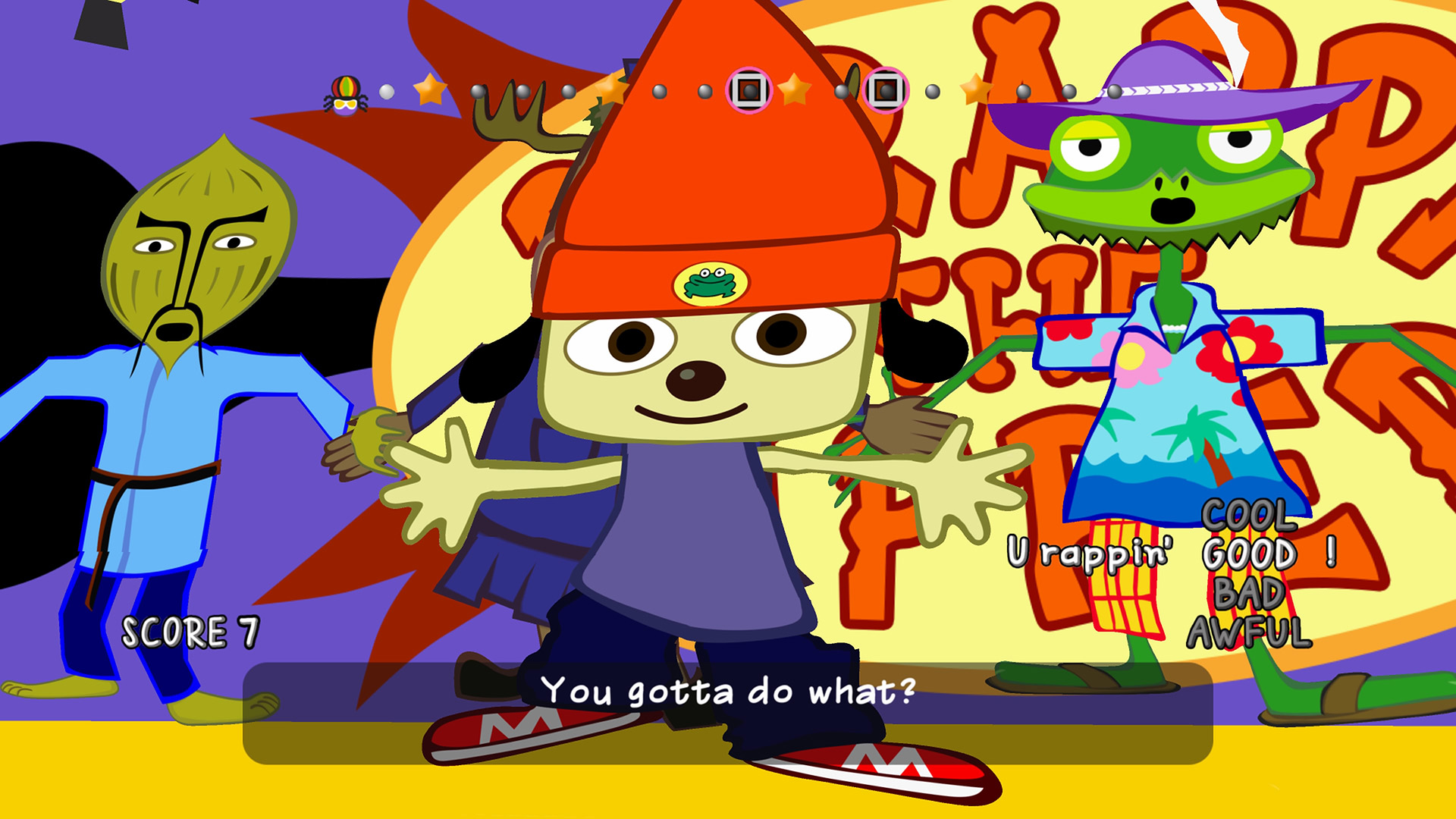

This led to the "Cool" mode. For the uninitiated, if you perform well enough, the teacher stops rapping and lets you go wild. The UI disappears. You’re just jamming. This was revolutionary. It moved the player from being a passive observer to an active participant in the composition. Honestly, modern games like Hi-Fi Rush owe their entire existence to the logic established in these early Sony titles.

Why Rodney Greenblat’s Art Still Holds Up

We need to talk about the visuals. Most 3D games from 1996 look like a muddy pile of polygons now. You can barely tell what you're looking at in most early PS1 titles. But because Rodney Greenblat chose a 2D "paper" aesthetic in a 3D world, Parappa is timeless.

The characters have no thickness. They flip around like cardboard cutouts. This wasn't just a stylistic choice; it was a clever technical workaround for the hardware limitations of the time. By not trying to be "realistic," the game avoided the uncanny valley entirely. It’s vibrant. It’s loud. It feels like a Saturday morning cartoon directed by someone with a very specific, very cool record collection.

👉 See also: Why LEGO Batman 2: DC Super Heroes Still Matters a Decade Later

The Sequel Struggle and the Um Jammer Lammy Pivot

By 1999, the world wanted more. But instead of a direct sequel, we got Um Jammer Lammy.

This is where the franchise got truly experimental. Instead of rapping, you were playing a guitar. Lammy, a shy lamb in a band called MilkCan, replaced Parappa as the protagonist. The stakes were higher. The music shifted from hip-hop to rock, punk, and even some strange space-age pop.

Many fans actually prefer Lammy. The mechanics felt a bit tighter, and the "fever" of the music was more intense. Plus, it featured one of the most bizarre levels in gaming history where you literally play a guitar to soothe a room full of crying babies. It was peak NanaOn-Sha.

Then came Parappa the Rapper 2 on the PlayStation 2 in 2001.

- The graphics were smoother.

- The music was arguably some of the best in the series (thanks to the "Toasty" level).

- The plot involved everything in the world turning into noodles.

But something was missing. The novelty had worn off for the general public. While the hardcore fans loved the "Noodle Syndicate" storyline and the improved freestyle mechanics, the game didn't set the charts on fire. It felt like the industry was moving toward the plastic-peripheral era of Dance Dance Revolution and Guitar Hero. The era of the "button-press" rhythm game was fading, replaced by the "hardware" rhythm game.

The Truth About the 4K Remaster

In 2017, Sony released PaRappa the Rapper Remastered for the PS4. It looked gorgeous. The 2D art was cleaned up into crisp 4K lines. However, it highlighted a major problem that critics and fans still debate: input lag.

On old CRT televisions, there was virtually no delay between pressing a button and the console registering it. On modern flat-screen TVs, that millisecond of lag kills a game as precise as Parappa. People who hadn't played the game in twenty years picked up the remaster and thought they had lost their rhythm. In reality, the game's engine was struggling to keep up with modern display tech.

If you’re going to play Parappa the Rapper games today, you basically have two choices. You can play the remaster and spend thirty minutes digging through your TV’s "Game Mode" settings to minimize lag, or you can find a PSP and play the 2006 port. Ironically, the PSP version—despite its smaller screen—is often cited by speedrunners as one of the most "honest" ways to play because the hardware is dedicated to that specific input speed.

Misconceptions About "Easy" Gameplay

A lot of people think these games are for kids. They look cute, so they must be easy, right?

Wrong.

The "Prince Fleaswallow" stage in the first game or the "Mooseini" stage in the second are absolute gauntlets. The game doesn't just ask you to copy what the teacher says; it asks you to internalize the rhythm and then add your own flair without breaking the meter. If you drop from "Good" to "Bad," the music actually changes. The vocals get distorted. The background music loses its bass. It’s a psychological attack as much as a mechanical one.

The Legacy of the Hat

Why does this dog still matter in 2026?

👉 See also: Fallout 4 Nude Mod: Why the Modding Community Still Can't Get Enough

It’s about the "Vibe." We live in an era of hyper-monetized, live-service games that want 100 hours of your time. Parappa the Rapper games want 45 minutes of your time. They are short, punchy, and overflowing with personality. They represent a time when Sony was willing to be the "weird" kid on the playground.

The influence is everywhere. You see it in the character designs of Splatoon. You hear it in the lo-fi beats of indie titles like Friday Night Funkin'. Even the "Ugh!" and "Yeah!" sound bites have become part of the universal language of gaming.

Actionable Steps for the Aspiring Master

If you want to experience the series properly without pulling your hair out, follow this specific path:

- Calibrate your hardware: If playing on PS4 or PS5, turn off all "motion smoothing" on your television. It is the enemy of the rap.

- Listen, don't just watch: The visual prompts on the bar are actually slightly misleading in the first game. Close your eyes for a second and just listen to the teacher's flow. Your thumb will follow the ear better than the eye.

- Embrace the Freestyle: Don't just press the buttons once. Double-tap them. Experiment with the rhythm between the icons. That is how you trigger the "Cool" rating, which is the only way to see the true ending of certain stages.

- Track down the soundtracks: The music stands alone. Pieces like "Cheap Cheap The Cooking Chicken" are genuine feats of composition that blend multiple genres effortlessly.

The world might have moved on to VR and photorealistic ray-tracing, but there is still something incredibly grounding about a dog who just wants to impress a flower girl by learning how to bake a cake. It’s simple. It’s honest. It’s got rhythm.

To get the most out of the experience, start with the PSP port of the original title if you can find it; it bridges the gap between the original's charm and modern accessibility. If you're stuck on a specific level—looking at you, Stage 4—try muting the TV for one run. Sometimes the visual icons are actually more accurate than the audio cues in the port versions, and removing the "sensory overload" of the music can help you nail the pattern once and for all. Once you have the pattern in your muscle memory, turn the sound back up and let the groove take over.