History has a weird way of obsessing over "what ifs." You've probably heard the one about the failed artist who, had he just been accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, might have spent his life painting serene landscapes instead of orchestrating a global catastrophe. It’s a compelling narrative. It's also a bit of a simplification. When you actually look at the paintings by Adolf Hitler, you aren't looking at the work of a misunderstood genius or even a particularly creative soul. You're looking at the output of a man who was, by all technical accounts, a very persistent amateur with a deep-seated lack of imagination.

He produced hundreds of works. Some say thousands.

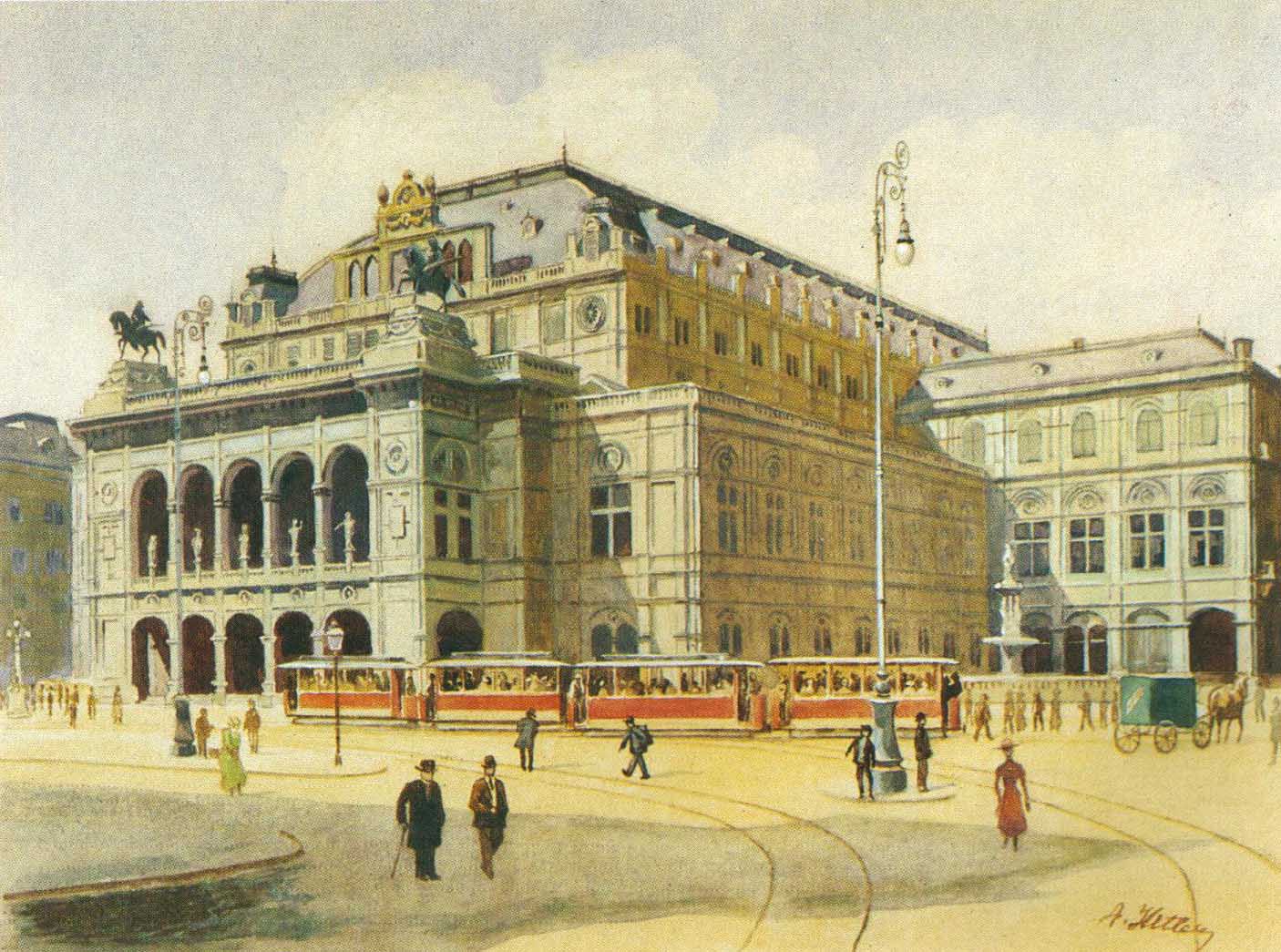

Most were postcards. He'd sit in the men's hostels of Vienna, copying scenes of the city—St. Stephen's Cathedral, the Opera House, the Parliament—and selling them to tourists or frame makers. It was a hustle. Honestly, he wasn't doing it for the "sanctity of art." He was doing it to keep from getting a real job, something he famously detested. If you see one of these pieces today, the first thing you notice is how... empty they feel.

The Technical Reality of His Work

If you ask an art historian like Birgit Schwarz or a critic like John Gunther (who famously called Hitler's work "prosaic" and "utterly devoid of rhythm"), they’ll tell you the same thing. The perspective is often wonky. The figures—the people—are tiny, stiff, and look like afterthoughts. It’s as if he couldn't handle the complexity of a human face or the fluid motion of a crowd.

He loved buildings. He obsessed over the "stone and mortar" of Vienna and later Munich.

But even his architectural drawings lacked soul. They were drafting exercises. In his two attempts to enter the Vienna Academy in 1907 and 1908, the examiners were blunt. They told him he lacked "fitness for painting" and suggested he try architecture instead. But because he didn't have a high school diploma (the Realschule certificate), he couldn't even enroll in architecture school. He was stuck in a loop of producing "uninspired" watercolors that lacked any of the avant-garde energy sweeping through Europe at the time. While Klimt and Schiele were tearing up the rulebook in the same city, Hitler was busy trying to perfect the exact number of windows on a cathedral.

✨ Don't miss: Who Has Trump Pardoned So Far: What Really Happened with the 47th President's List

He hated modernism. Obviously. He later called it "degenerate."

Where Are These Paintings Now?

This is where the story gets legally and ethically messy. After the war, the U.S. Army seized a significant number of his works. A lot of them are still held by the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. They aren't on public display. The U.S. government keeps them under lock and key, mostly to prevent them from becoming "relics" for neo-Nazi groups.

Then there are the private collections.

Every few years, an auction house in Nuremberg or somewhere in the UK will try to sell a batch of paintings by Adolf Hitler. It always causes a PR nightmare. In 2015, a watercolor of Neuschwanstein Castle sold for roughly $100,000. People get outraged. Rightly so. But the collectors? They aren't usually art lovers. They are either historical completists or, more disturbingly, individuals who find some sort of power in the "dark provenance" of the items.

The market is also flooded with fakes. Since his style was so generic and easy to mimic, it’s a forger’s dream. Konrad Kujau, the guy behind the infamous "Hitler Diaries" hoax in the 1980s, also spent years cranking out fake Hitler paintings and selling them to unsuspecting (and perhaps overly eager) collectors. Basically, if you find a "Hitler" in your grandma's attic, there's a 99% chance it's a fake or a work by a different "A. Hitler"—of which there were several in Germany at the time.

🔗 Read more: Why the 2013 Moore Oklahoma Tornado Changed Everything We Knew About Survival

The Ethics of the Gavel

Should these things even be sold? It’s a debate that never ends. Some argue they belong in museums as educational tools to show the "banality of evil." Others think they should be burned. Most reputable auction houses like Sotheby's or Christie's won't touch them with a ten-foot pole. The ones that do often hide behind the "historical document" defense.

But let's be real. It’s about the money.

What the Art Tells Us About the Man

There’s a temptation to psychoanalyze these paintings. You look at a lonely house on a hill and think, "Ah, the isolation of the future dictator." But that’s probably reaching. The real insight isn't in what's in the paintings, but what's missing.

- There is no emotion.

- There is no experimentation.

- There is no empathy for the human form.

His art was purely transactional. It was a way to prove he was an "artist" without doing the hard work of creative expression. He viewed himself as a misunderstood genius, a classic trope for someone who refuses to accept their own mediocrity. This grandiose self-image carried over into his political life. He didn't just want to lead Germany; he wanted to be the "Architect of the Third Reich." He viewed the state as a canvas and the people as a medium to be shaped.

It’s a chilling thought. The same man who couldn't quite get the perspective right on a doorway eventually tried to redraw the borders of the entire world.

💡 You might also like: Ethics in the News: What Most People Get Wrong

Identifying a Genuine Work

If you're looking into this for historical research, you have to be incredibly careful with your sources. The Price Guide to the Paintings, Drawings and Watercolors of Adolf Hitler by Billy F. Price is often cited, but even that volume has been criticized for including works of questionable authenticity.

- The Signature: He usually signed as "A. Hitler" or "Adolf Hitler." The script changed over the years, moving from a more legible Latin script to the cramped Sütterlin style later in life.

- The Subject: Almost exclusively landscapes, flowers, or buildings. Portraits are extremely rare and usually very poorly executed.

- The Medium: Mostly watercolors and oils. He wasn't big on charcoal or abstract sketches.

Dealing With the Legacy

The fascination with these paintings isn't about art. It’s about trying to find a "glitch" in the matrix of history. We want to see a monster in the brushstrokes. But the reality is more boring and, in a way, more frightening. The paintings are dull. They are the work of a person who saw the world in a very rigid, traditionalist, and unimaginative way.

Understanding the history of these works helps strip away the "mystique" that some try to build around his early life. He wasn't a great artist denied his due. He was a mediocre painter who found a different, much more destructive way to impose his narrow vision on the world.

Actionable Steps for Researchers and Collectors

If you're navigating the murky waters of historical artifacts from this era, keep these points in mind to stay on the right side of both ethics and authenticity:

- Consult the Experts First: Before taking any "found" artwork seriously, contact the U.S. Army Center of Military History or the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv). They have the most extensive databases for cross-referencing known works.

- Verify Provenance Scrupulously: A painting is only as real as the paper trail behind it. If a piece doesn't have a verifiable chain of ownership dating back to the 1930s or 40s, it's almost certainly a Kujau-style forgery.

- Understand the Legal Landscape: Selling or displaying Nazi-related items is strictly regulated in many countries, especially Germany (under Paragraph 86a of the German Criminal Code). Always check local laws before attempting to transport or trade such items.

- Support Educational Context: If you're an educator or student, focus on how the art was used as a propaganda tool after 1933. The "artist-leader" persona was a carefully crafted myth designed to soften his image.