You’ve probably seen the posters. A majestic, glowing swirl of stars with a tiny arrow pointing to a nondescript speck labeled "You Are Here." It looks official. It looks like a photograph. But honestly? It isn't. We have never, ever taken a photo of the Milky Way from the outside. To do that, we’d have to send a camera hundreds of thousands of light-years above the galactic plane. For context, Voyager 1—our furthest-traveling spacecraft—hasn't even left the "driveway" of our solar system after nearly fifty years of flying.

So, how do we actually build a map of our galaxy?

💡 You might also like: Downtown Dallas Delivery Robots: What’s Actually Happening on the Sidewalks

It’s basically like trying to map out the floor plan of a massive, crowded nightclub while you’re stuck sitting in a booth in the very back corner. You can see the people right in front of you. You can see the glow of the neon lights over the bar. But there's a giant pillar in your way, a lot of smoke, and the music is so loud you can't hear what's happening in the VIP lounge. Mapping the Milky Way is an exercise in extreme cosmic deduction. We use radio waves, infrared sensors, and the sheer grit of mathematical modeling to figure out where the "walls" are.

The Great Dust Problem

Space is dirty. That’s the first thing you have to understand if you want to find your way around. Between us and the center of the galaxy lies a staggering amount of interstellar dust and gas. To our eyes, this stuff is opaque. It blocks visible light completely. If you look up at the night sky from a dark spot, you'll see dark rifts in the Milky Way. Those aren't empty spaces; they're massive clouds of soot-like particles hiding millions of stars.

Astronomers like Edward Barnard spent years cataloging these "dark nebulae," but it wasn't until we started using different "eyes" that the map began to make sense. We had to stop looking at light and start looking at heat and radio signals.

Breaking Through with Radio and Infrared

In the 1950s, we got a huge break. Scientists discovered the 21-centimeter line. This is a very specific frequency of radio waves emitted by neutral hydrogen atoms. Since hydrogen is everywhere, we could finally "see" through the dust. By measuring the Doppler shift of these signals—basically seeing if the "pitch" of the radio wave changed because it was moving toward or away from us—we started to trace the spiral arms.

Then came the Spitzer Space Telescope and eventually James Webb. These instruments look in infrared. Infrared passes through dust like it's not even there. It’s the difference between trying to look through a brick wall and looking through a window. Suddenly, the "bar" at the center of our galaxy became clear. We aren't just a simple spiral; we are a barred spiral. That was a massive correction to the map of our galaxy that only happened relatively recently in the grand scheme of science.

Gaia and the Billion-Star Benchmark

The real game-changer is a mission called Gaia. Launched by the European Space Agency, this satellite is currently doing the most "human" version of mapping possible: it’s just looking at things very, very carefully.

Gaia measures parallax.

👉 See also: Buying an Echo Dot from Walmart: What Most People Get Wrong

Hold your thumb out at arm's length. Close your left eye. Now close your right eye and open the left. Your thumb "jumps" against the background. That's parallax. By doing this with stars from different sides of the Earth's orbit, Gaia can calculate the exact distance to over a billion stars. A billion sounds like a lot. It is! But remember, there are maybe 400 billion stars in the Milky Way. Gaia is mapping about 1% of the total population.

Even with just 1%, we’ve found some weird stuff. We discovered that our galaxy isn't a flat disk. It's warped. It’s flared at the edges, kinda like a frisbee that stayed out in the sun too long. This warping likely comes from the gravitational tug of neighboring dwarf galaxies that are currently being "eaten" by the Milky Way.

The Arms We Live In

Most people can name the big parts of the map: the Perseus Arm, the Scutum-Centaurus Arm, and the Sagittarius Arm. We used to think we lived in a tiny, insignificant "spur" called the Orion-Cygnus Arm.

Recent data suggests we might have been selling ourselves short.

The Orion Arm might be much more substantial than just a bridge between two larger structures. Research led by Ye Xu and colleagues using the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) has shown that the pitch angle and length of our local arm are more comparable to the major arms than we previously thought. It turns out, our neighborhood is a bit more "upscale" than the old maps suggested.

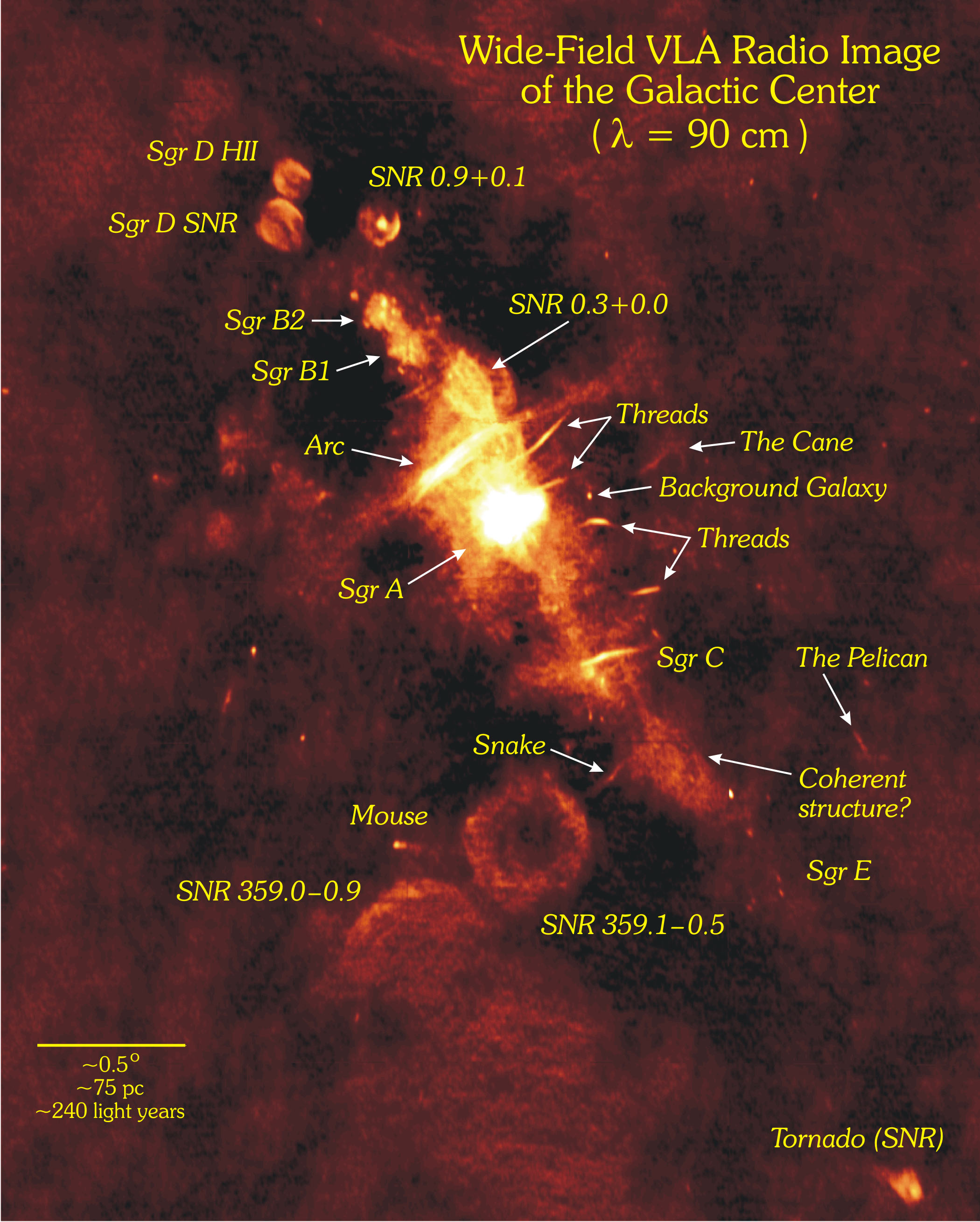

The Galactic Center: The Point of No Return

At the heart of the map of our galaxy lies Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). This is a supermassive black hole with the mass of 4 million suns. For a long time, this was a theoretical point on the map. We knew something heavy was there because we watched stars like S2 whipping around it at terrifying speeds—about 3% of the speed of light.

In 2022, the Event Horizon Telescope gave us the "photo." It’s a blurry, orange donut of glowing gas. It confirmed the "anchor" of our entire galactic map. Everything we are—the sun, the planets, the Oort cloud—is orbiting that dark heart. We are currently about 26,000 light-years away from it. Close enough to be held in its grip, far enough away to not get spaghettified anytime soon.

Why the Map Keeps Shifting

Science isn't a collection of static facts. It's a process of being less wrong every day. Our map changes because our tech gets better. For instance, there’s a massive debate right now about how many spiral arms we actually have.

💡 You might also like: How Much Is a Replacement AirPod: What the Apple Store Won't Mention Up Front

- Some data points to four major arms.

- Other data suggests two major arms and a bunch of fragmented "flocculent" pieces.

- Newer 3D maps of Cepheid variables (stars that pulse predictably) show the disk is much more "wrinkled" than 2D diagrams suggest.

We also have to account for Dark Matter. If you only map what you can see, the map doesn't work. The stars at the edge of the galaxy are moving way too fast. Based on the visible mass, they should be flying off into deep space like kids being thrown off a merry-go-round that's spinning too quickly. Something invisible is holding them in. This "dark matter halo" is arguably the most important part of the map of our galaxy, but we have no idea what it actually looks like. We just know it's there because the math demands it.

Your Place in the Neighborhood

If you want to understand the scale, try this. Imagine the entire Milky Way is the size of the United States. In this map, our solar system would be about the size of a United States quarter.

The distance between the sun and the next nearest star (Proxima Centauri) would be about the length of two football fields.

Space is mostly... space.

When you look at a map of our galaxy, you're looking at a graveyard and a nursery at the same time. You’re seeing the remnants of dead stars (supernova remnants) and the "Pillars of Creation" where new ones are being born. It’s a dynamic, breathing entity.

How to Explore the Map Yourself

You don't need a PhD to start visualizing this. The tools available now are genuinely incredible compared to what we had even ten years ago.

- Gaia Sky: This is a real-time, 3D astronomy visualization software that uses the actual Gaia mission data. You can "fly" through the stars. It’s free. It’s heavy on your computer's RAM, but it's the closest you'll get to a real starship experience.

- The Milky Way Project: This is a citizen science initiative where you can help look at infrared images from the Spitzer Space Telescope to find "bubbles" in space—areas where massive stars are blowing holes in the interstellar medium.

- WorldWide Telescope: Run by the American Astronomical Society, this allows you to overlay different maps (radio, X-ray, visible) on top of each other to see how the galaxy changes when you change your perspective.

Don't get too hung up on the "perfect" image. The maps we have are masterpieces of inference. They represent thousands of years of humans looking at the ceiling and wondering what's behind the clouds. Every time we launch a new telescope, we have to erase a few lines and draw new ones. That’s not a failure; it’s the whole point.

Moving Forward with Galactic Knowledge

To get a true feel for the scale of the Milky Way, your next move should be to download an app like SkySafari or Stellarium. Go outside on a moonless night. Find the "Great Rift"—that dark lane splitting the stars. Now that you know that's not empty space, but actually a massive "wall" of dust blocking your view of the galactic center, the night sky feels a lot more three-dimensional.

If you're feeling more academic, dive into the ESA Gaia Archive. It’s public. You can look at the raw data being used to build the next generation of galactic charts. Just remember: you're part of the map. Every atom in your body was cooked inside one of those dots on the chart. You aren't just looking at the galaxy; you're the galaxy looking at itself.