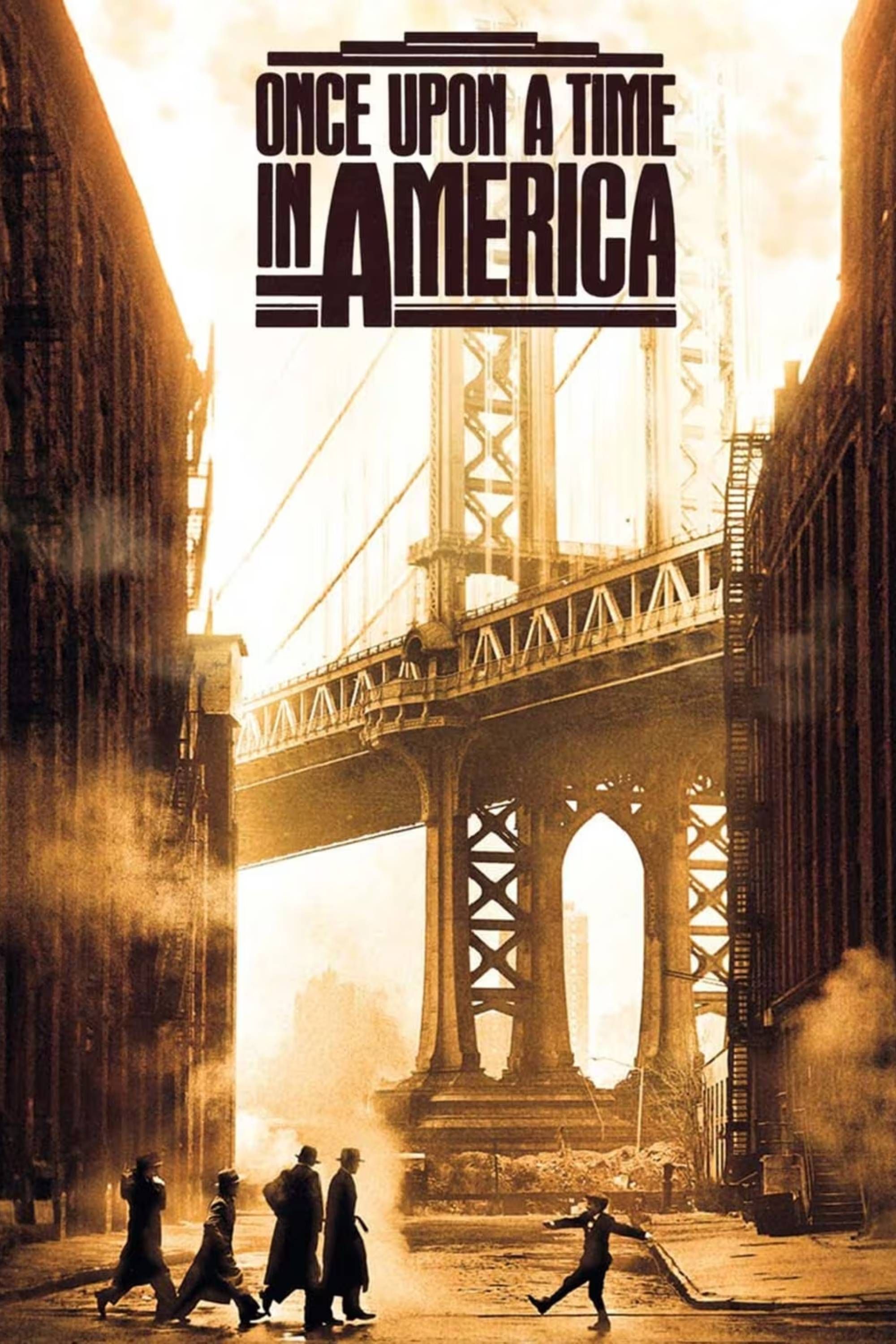

Sergio Leone didn’t just make a movie; he built a tomb for the American Dream. Honestly, if you’ve ever sat through the full four-hour cut of Once Upon a Time in America, you know that "watching" isn't really the right word for it. It’s an experience that clings to you like the smell of old cigar smoke in a velvet-lined room. It’s heavy. It’s problematic. It’s also, quite arguably, the most beautiful thing ever put on celluloid.

The film is a labyrinth. Most people walk into it expecting a Jewish version of The Godfather, but they walk out feeling like they’ve just woken up from a fever dream. That’s because Leone wasn't interested in the logistics of the mob. He wanted to talk about time. He wanted to talk about how memory lies to us.

The Messy Reality of the Movie Once Upon a Time in America

Let’s be real for a second. The production was a disaster. Leone spent over a decade trying to get this thing made. He turned down The Godfather—can you imagine?—just to keep his schedule open for this epic. He was obsessed with the Harry Grey novel The Hoods, which was written by a real-life gangster while he was serving time in Sing Sing.

The movie Once Upon a Time in America is essentially a story told in three acts, but not the kind you learned about in English class. We jump between the 1920s, the 1930s, and 1968. Robert De Niro plays "Noodles" with this haunting, quiet stillness. He’s a monster, yet you can’t look away. Beside him is James Woods as Max, the ambitious, charismatic, and ultimately sociopathic best friend. Their chemistry is the engine of the film, but the fuel is pure tragedy.

Why the 1984 US Release Almost Killed It

You've probably heard the horror stories. When the film first hit American theaters in 1984, the distributors—The Ladd Company—did something unforgivable. They hacked the 229-minute masterpiece down to a 139-minute "straightforward" crime flick. They took Leone’s intricate, non-linear timeline and rearranged it into chronological order.

It was a bloodbath.

👉 See also: Nothing to Lose: Why the Martin Lawrence and Tim Robbins Movie is Still a 90s Classic

Critics hated it. Audiences were confused. Roger Ebert, who eventually championed the film, famously called that short version a "travesty." It took years for the restored European cut to find its way to the States, finally allowing people to see what Leone actually intended. Without the jumps in time, the movie loses its soul. The whole point is that Noodles is looking back at his life from 1968, trying to figure out where it all went wrong. If you watch it in order, it's just a story about some guys selling booze.

Deciphering the Opium Dream Theory

If you haven't seen the ending, look away now.

Wait, actually, stay. Even if you’ve seen it, you probably still have questions. The final shot of the movie Once Upon a Time in America is one of the most debated frames in cinema history. Noodles is in an opium den in the 1930s. He looks up at the camera and breaks into this wide, eerie, drug-induced grin.

Many scholars and fans—including the late, great James Woods—argue that the entire 1968 sequence is actually just an opium dream. In this interpretation, Noodles never actually grows old. He never returns to New York. He’s just high, imagining a future where he can find some kind of closure for the betrayal he committed.

Leone himself was always cagey about this. He liked the ambiguity. He wanted you to feel that sense of "what if?" that defines old age. It makes the movie less of a historical document and more of a psychological profile.

✨ Don't miss: How Old Is Paul Heyman? The Real Story of Wrestling’s Greatest Mind

The Music That Won't Leave Your Head

We cannot talk about this film without talking about Ennio Morricone. Most composers write the music after the film is edited. Not here. Leone had Morricone write the score before they even started filming. He would actually play the music on set to help the actors get into the right headspace.

The "Deborah’s Theme" is arguably the most heartbreaking piece of music ever written for a film. It captures that specific ache of a love that was doomed from the start. When that pan flute kicks in during the Cockeye’s song, you’re instantly transported to a rainy street corner in the Lower East Side. It’s visceral.

The Problematic Legacy of Noodles

We have to address the elephant in the room. This movie is incredibly difficult to watch because of its treatment of women. The scenes involving Tuesday Weld and Elizabeth McGovern are brutal. Noodles is not a hero. He’s a deeply flawed, violent, and often reprehensible man.

Leone doesn't shy away from this. He doesn't try to make Noodles "cool" in the way some directors do with gangsters. He shows the ugliness of the lifestyle. The violence isn't stylized; it's jarring and uncomfortable. This is why the movie Once Upon a Time in America remains so polarizing. It asks the audience to spend four hours inside the mind of a man who has done unforgivable things.

The 2012 Restoration and Beyond

In 2012, a 251-minute version was screened at Cannes, thanks to the efforts of Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation. They found deleted scenes that filled in some of the gaps, particularly regarding Noodles’ relationship with Eve and his final confrontation with Max (now Secretary Bailey).

🔗 Read more: Howie Mandel Cupcake Picture: What Really Happened With That Viral Post

- The deleted scenes were found in poor condition, so the visual quality fluctuates.

- The extra footage adds depth to the 1960s political subplot.

- It makes the ending feel even more final and hollow.

While some purists prefer the 229-minute "International Cut," the extended version is a fascinating look at what Leone might have released if he had his way. It’s a massive, sprawling mess of a movie, and that’s exactly why it works. It feels like a life—long, complicated, and full of regrets.

How to Actually Watch It Today

If you’re going to dive into the movie Once Upon a Time in America, you need to prepare. This isn't a "Netflix and chill" situation. You need a dedicated afternoon.

- Find the 229-minute version. Don't settle for anything less. The rhythm of the film depends on its length.

- Turn off your phone. The long, lingering shots of people just staring at each other are where the emotion lives. If you’re checking Twitter, you’ll miss the subtle shift in De Niro’s eyes.

- Listen to the silence. Leone used silence as a character. The sound of a telephone ringing for minutes on end, or the clinking of a teaspoon against a ceramic cup, is meant to build tension.

The movie is a eulogy for a specific type of filmmaking. We don't see movies like this anymore because they cost too much and take too long. Studios today want "content," but Leone wanted to build a monument.

Ultimately, the film asks one question: Can you ever really go home again? For Noodles, the answer is a resounding no. The New York he knew is gone, his friends are dead or transformed, and the only thing left is the memory. And memories, as the film shows us, are the most dangerous things we own.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

If this article piqued your interest, your next move should be to track down the 2014 Blu-ray or the 4K restoration. Look specifically for the "Extended Director's Cut." Once you've finished the film, read The Hoods by Harry Grey to see just how much of the "real" underworld Leone managed to capture. Finally, spend an evening with the Morricone soundtrack on high-quality headphones. It changes the way you perceive the film's pacing entirely.