Leni Riefenstahl is a name that carries a massive, heavy asterisk. You can't talk about her 1938 masterpiece, Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations, without acknowledging the elephant in the room: it was commissioned by the Third Reich. It’s uncomfortable. It’s messy. Yet, if you’re a fan of how sports are filmed today—think the slow-motion sweat of a Nike commercial or the soaring crane shots on an NFL broadcast—you’re looking at her fingerprints.

She basically invented the visual language of modern athletics.

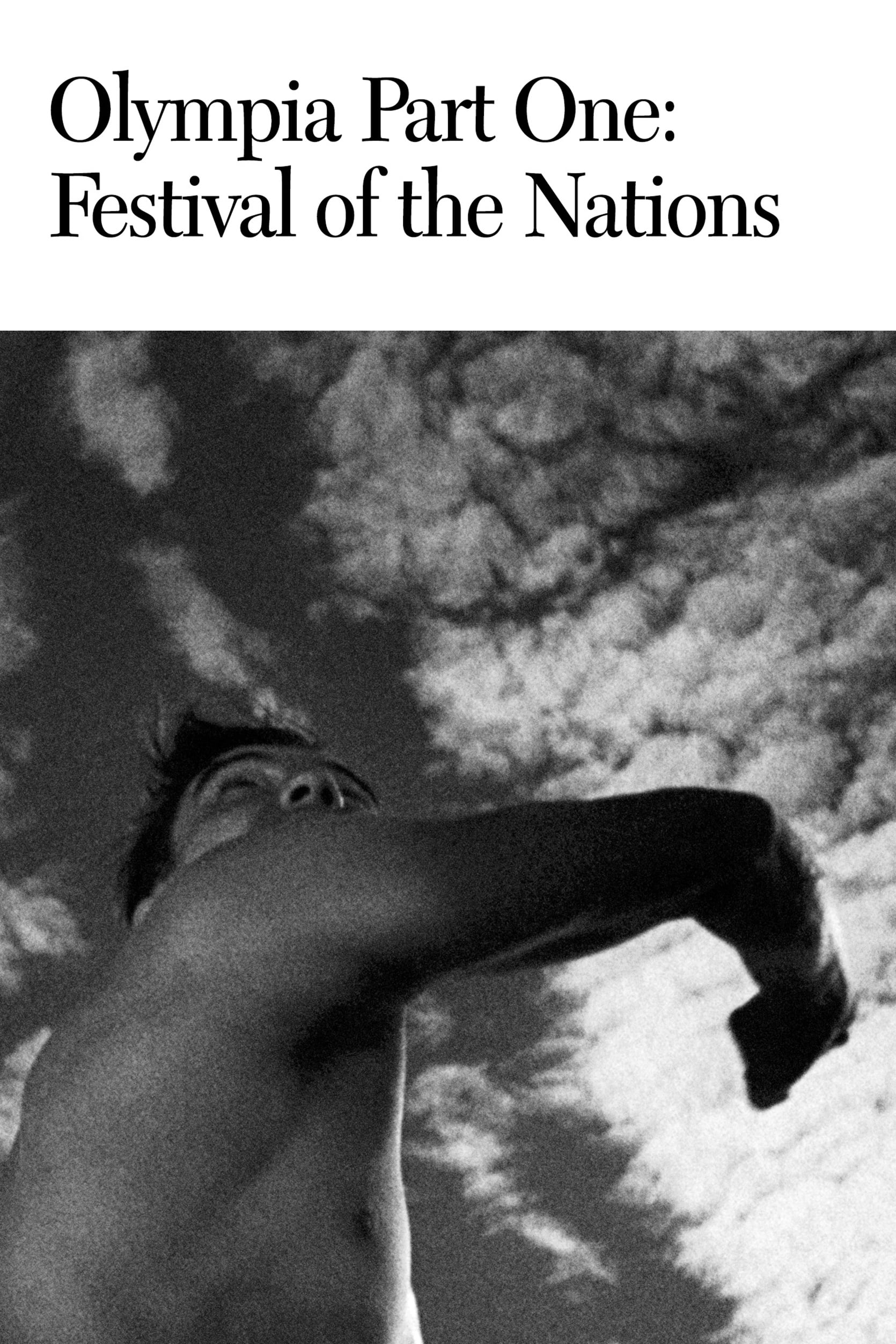

Before this film, sports photography was boring. It was flat. It looked like someone just pointed a camera at a field and hoped for the best. Riefenstahl changed that by treating the human body like a moving sculpture. This wasn't just a newsreel of the 1936 Berlin Games; it was a high-budget, high-concept epic that took nearly two years to edit.

The Technical Madness Behind the Lens

Honestly, the sheer scale of the production for Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations was absurd for the 1930s. We are talking about a crew of 170 people. They didn’t just show up with a few cameras. They dug pits in the ground to get low-angle shots of high jumpers against the sky. They built tiny catapults to launch cameras alongside the athletes.

They even designed underwater housings for cameras to capture divers.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Books Like The Lunar Chronicles Without The Cringe

Think about that. In 1936, they were waterproofing heavy, hand-cranked film equipment just to get a shot of a splash. It was obsessive. This obsession is why the film feels so visceral even now. When you watch the hammer throw, the camera follows the weight in a way that makes you feel the centrifugal force. It’s dizzying.

Pushing Past the Propaganda Label

It’s easy to dismiss this as pure propaganda. Certainly, the "Prologue" of the film—which links ancient Greece directly to Nazi Germany through shots of statues and "Aryan" looking athletes—is heavy-handed. It was designed to promote an ideology of physical perfection.

But then Jesse Owens happens.

If this were purely a Nazi puff piece, Owens wouldn’t be the star. Yet, in Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations, the African American sprinter is the undisputed hero. Riefenstahl spends an enormous amount of screen time on him. She captures his grace, his speed, and the sheer dominance he exerted over the "master race" competitors. It’s a fascinating contradiction. While the Nazi regime wanted to showcase their supposed superiority, the film itself couldn't help but document the reality of Owens’ brilliance.

The editing during the 100-meter dash is a masterclass in tension. You see the twitching muscles, the focused eyes, and the explosion off the blocks. It’s pure cinema.

Why the Editing Took Two Years

Riefenstahl sat on over 1.2 million feet of film. That’s a staggering amount of celluloid to sort through without digital tools. She spent months in a dark room, literally cutting and taping strips of film together.

She wasn't just looking for the winner of the race. She was looking for the rhythm.

If you watch the marathon sequence—which actually appears in the second part, but the stylistic groundwork is laid here—the editing mimics the heartbeat of a runner. In Part One, during the discus and javelin events, the cuts are timed to the physical exertion. It’s rhythmic. It’s almost musical. This "montage" style is exactly what you see in every Olympic intro video today. Every single one.

The Controversial Legacy of the 1936 Berlin Games

We have to talk about the context. The 1936 Games were the "Nazi Games." Hitler wanted to use the event to show the world a peaceful, prosperous Germany. Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations was the crown jewel of that PR campaign.

Critics like Susan Sontag have argued that the film's "fascinating fascism" lies in its glorification of the strong over the weak. It’s a valid point. The film focuses on the elite, the powerful, and the beautiful. It ignores the struggle or the "ugly" parts of sport.

Yet, film historians like Kevin Brownlow have pointed out that Riefenstahl’s techniques were revolutionary regardless of the politics. It’s a tug-of-war for the viewer. Can you admire the art while hating the patron? Most film students spend weeks debating this exact question.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Prologue"

People often think the film starts right at the stadium. It doesn't.

It starts in the ruins of the Acropolis. The first twenty minutes are a slow, misty journey through Greek history. It’s meant to establish a lineage. The camera lingers on the Discobolus (the discus thrower) and then dissolves into a real athlete in the same pose.

It’s a bit pretentious, sure. But it was the first time a sports film tried to be "Art" with a capital A. It wasn't just about who won the gold medal; it was about the "Olympic Spirit" (or at least the version of it the producers wanted you to see).

How to Watch It Today Without Feeling Weird

If you’re going to watch Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations, go in with your eyes open. Recognize the manipulation. Notice how the crowd is filmed—thousands of people moving in unison, a favorite trope of Riefenstahl’s that she perfected in Triumph of the Will.

But also look at the athletes.

Look at the sweat. Look at the genuine exhaustion on their faces. Behind the political theater, there were real people pushing their bodies to the limit. The film captures that human element better than almost any documentary of the era.

Actionable Insights for Film and History Buffs

If you want to truly understand the impact of this film, don't just read about it. Do these three things:

- Watch the 100m Final: Compare the camera angles in Olympia to a modern Olympic broadcast. You’ll be shocked at how many of the "standard" angles were first used by Riefenstahl’s crew.

- Research the "Diving" Sequence: Even if you only watch five minutes, make it the diving. The way she flips the footage and plays with gravity is genuinely trippy. It’s often cited as the most beautiful sequence in sports cinema history.

- Read the Backstory of Jesse Owens and Riefenstahl: There is a lot of debate about their relationship. Some say she was enamored with his talent; others say she was forced to include him. Understanding this tension makes the viewing experience much more complex.

The reality of Olympia Part One Festival of the Nations is that it is both a masterpiece of cinematography and a tool of a horrific regime. You can’t separate them. But you can learn from the craft while remaining critical of the message.

To truly grasp the evolution of sports media, you have to look at the raw footage. Find a restored version. Pay attention to the sound design—much of it was added in post-production because the cameras were too loud to record live audio. This artifice is part of the genius. It’s a constructed reality that feels more "real" than the truth. That is the power of great, albeit problematic, filmmaking.