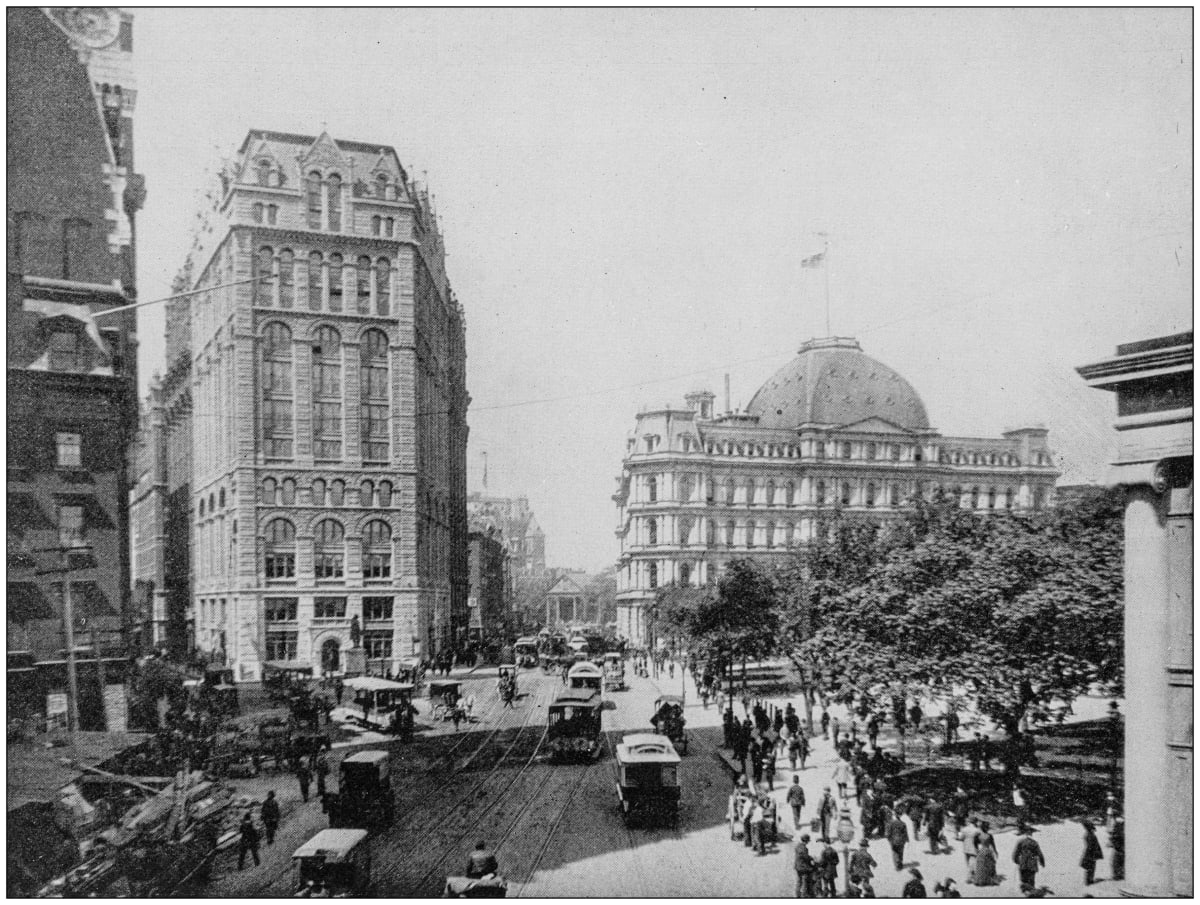

You’ve seen them. Those grainy, sepia-toned snapshots of a city that feels like a fever dream. Maybe it’s a horse-drawn carriage clattering down a dirt-path Broadway or a group of ironworkers eating lunch on a steel beam suspended 800 feet above a sidewalk that hasn't even been paved yet. Old New York photographs aren’t just nostalgic wallpaper for Midtown diners; they are the only honest witnesses we have left to a city that is constantly trying to murder its own past.

New York is a palimpsest. It’s a place that builds over itself every twenty years. If you stand on the corner of 42nd and Vanderbilt today, you’re looking at glass and steel, but the camera remembers the dirt, the coal smoke, and the sheer, chaotic noise of a city being born out of the mud.

Honestly, most people look at these images and see "the good old days." That’s a mistake. These photos show a city that was often loud, filthy, and incredibly dangerous. But they also show a level of architectural ambition that we’ve basically lost. When you look at the 1930s shots of the Chrysler Building’s needle being hoisted into place, you aren't just looking at a construction site. You’re looking at a statement of intent.

The obsession with the "Lost" City

Why do we care so much? It’s probably because New York changes faster than our brains can process. You go away for a weekend and your favorite deli is a bank. You leave for a year and a whole block of brownstones is a hole in the ground. Old New York photographs provide a temporary anchor. They give us a sense of "place" in a city that is fundamentally restless.

Take the work of Berenice Abbott. In the 1930s, she started a project called "Changing New York." She wasn't just snapping pretty pictures. She was documenting the friction between the 19th-century low-rise city and the soaring skyscrapers of the modern era. Her shot of the "Flatiron Building" isn't just a photo of a triangle-shaped skyscraper; it’s a study in how the wind whipped around those new steel canyons, famously creating the "23 Skidoo" phenomenon where men would hang out on the corner just to watch the wind lift women’s skirts.

The detail in these large-format negatives is insane. You can zoom into a photo of a Lower East Side pushcart market from 1905 and literally read the price of pickles on a wooden sign. You see the faces of people who had just stepped off a boat at Ellis Island, carrying everything they owned in a cardboard suitcase. It’s raw.

The Great Depression through a lens

The 1930s changed everything for photography in the city. Before that, a lot of photos were "pictorialist"—meant to look like paintings. Soft focus, dreamy, very upper-class. Then the crash happened. Suddenly, photographers like Walker Evans and Margaret Bourke-White were capturing the breadlines and the "Hoovervilles" in Central Park.

These aren't "pretty" old New York photographs. They are documents of survival.

🔗 Read more: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

One of the most famous—and controversial—images from this era is "Lunch atop a Skyscraper." You know the one. Eleven men sitting on a girder during the construction of the RCA Building (now 30 Rockefeller Plaza). For years, people thought it was a spontaneous snapshot. It wasn’t. It was a staged publicity stunt to promote the new real estate. But here’s the thing: even if it was staged, those men were actually 800 feet in the air without harnesses. The danger was real. The height was real. The Irish and Mohawk ironworkers were real.

Where to find the "Real" stuff

If you’re looking for the high-res, deep-dive history, you have to get away from the Pinterest boards and look at the actual archives. The New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections is a rabbit hole you might never come out of. They have over 900,000 items digitized.

Then there’s the Municipal Archives.

In the 1940s and again in the 1980s, the city sent photographers to take a picture of every single building in the five boroughs for tax purposes. Every. Single. One. If you live in an old building in New York, there is almost certainly a photo of your front door from 1940 sitting in a database right now. Seeing your own street with vintage cars and no graffiti—or way more graffiti, depending on the decade—changes how you walk to the subway the next morning. It really does.

- The 1940s Tax Photos: Gritty, black and white, capturing the city just before the post-war boom.

- The 1860s Civil War Era: Mostly Matthew Brady’s studio work; very stiff, but the fashion is incredible.

- The 1970s "Gritty" Era: Think Camilo José Vergara or Martha Cooper. This is the New York of The Warriors and Taxi Driver.

The Jacob Riis impact

We can't talk about old New York photographs without mentioning Jacob Riis. He was a police reporter who took his camera into the tenements of the Lower East Side in the late 1880s. He used a primitive flash—basically exploding powder—to light up the dark, windowless rooms where ten people slept in a space meant for two.

His book, How the Other Half Lives, didn't just win awards; it forced the city to change the law. It led to the Tenement House Act of 1901. This is where photography stops being "art" and starts being a weapon for social justice. When you look at a Riis photo of "Street Arabs" (homeless children sleeping on grates), it’s gut-wrenching. It’s a reminder that the "Gilded Age" was only gilded for the people at the top of the cake.

Why colorized photos are kind of a problem

There’s a huge trend right now of people using AI to colorize old New York photographs. It looks cool on Instagram. It makes the past feel "closer." But a lot of historians kind of hate it.

💡 You might also like: Blue Bathroom Wall Tiles: What Most People Get Wrong About Color and Mood

Why? Because it’s guesswork. AI doesn't know if a hat was navy blue or dark green. It just guesses based on common patterns. When we colorize these images, we’re often overwriting the actual historical record with a modern aesthetic. There is a specific mood in the silver-gelatin prints of the 1920s that color just ruins. The shadows in New York are part of its character. The way the sun hits the brownstone stoops in Brooklyn at 4:00 PM is a specific kind of gold that a computer can't quite get right yet.

The tech that made the city look this way

Early cameras needed a lot of light. That’s why in mid-1800s photos of New York, the streets often look empty. They weren't empty; people were just moving too fast for the slow shutter speeds to catch them. They became "ghosts" or vanished entirely. Only the buildings stayed still long enough to be recorded.

By the time we got to the 1920s and 30s, the Leica and other 35mm cameras allowed photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson to capture "the decisive moment." You could finally photograph a guy jumping over a puddle in the Meatpacking District without him being a blurry mess. This changed the energy of New York photography from "statuesque" to "vibrant."

How to start your own archive

You don't need to be a billionaire collector to own a piece of this. While original 19th-century daguerreotypes can cost thousands, "vernacular photography"—basically other people's family snapshots—is a goldmine.

Check out flea markets in Chelsea or the Brooklyn Navy Yard. You’ll find boxes of discarded polaroids and black-and-white prints from the 1950s. There’s something haunting about holding a physical photo of a family picnic in Prospect Park from seventy years ago. You don’t know who they are, but you know exactly where they were standing.

- Check the back of the photo. Dates and locations are often scrawled in pencil.

- Look at the cars. Automotive design is the easiest way to date an undated New York photo. A 1957 Chevy is a dead giveaway.

- Cross-reference with maps. Use the "NYC Seven Thousand Days" map or the NYPL’s "Chronology of New York" to see what the street layout looked like at the time.

The 1970s: The last "Old" New York?

For many, the 1970s and 80s represent the last era of "authentic" New York before the "Disneyfication" of Times Square. Photographers like Bruce Davidson spent years in the subway system, capturing a world covered in tags and layers of grime.

These old New York photographs are polarizing. Some people see them and remember a city that was failing. Others see a city that was incredibly creative and affordable for artists. When you look at a photo of a graffiti-covered 2-train from 1982, you aren't just seeing vandalism; you’re seeing the birth of a global art movement.

📖 Related: BJ's Restaurant & Brewhouse Superstition Springs Menu: What to Order Right Now

The city felt bigger then. Less monitored. More dangerous, sure, but also more alive in a weird way.

Moving forward with the past

So, what do you do with all this? Don't just scroll. If you’re a New Yorker, or even just a fan, use these images as a map.

Go to a location you see in an old photograph. Find the exact spot where the photographer stood. Look at what’s still there—a decorative cornice, a weirdly shaped window, a fire hydrant that’s been there since 1920. It’s a way of time traveling that actually works.

Identify the era by looking at the streetlights; those ornate "Bishop's Crook" posts are a classic sign of the early 20th century. Analyze the clothing to see the class dynamics—the divide between the silk-hatted strollers on 5th Avenue and the newsboys in the Bowery is stark. Support the archives that keep these things alive. The Museum of the City of New York has an incredible collection that needs public interest to stay funded.

Old photos aren't just about looking back. They’re about understanding that the city we live in now is just one version of a story that’s been being told for four hundred years. We’re just the latest characters.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Visit the NYPL Digital Gallery: Search for your own street address or neighborhood to see how it looked 100 years ago.

- Follow "OldNYC" on social platforms: This project maps NYPL photos directly onto a modern map of the city, making it easy to see "then and now" transitions.

- Check out the Library of Congress (LOC) Prints & Photographs Online Catalog: They hold thousands of high-resolution images by the Detroit Publishing Co. that show New York at the turn of the century in stunning detail.

- Look for "re-photography" projects: Study the work of photographers who recreate historic shots from the exact same angle to understand urban evolution.