You remember the smell of that computer lab? It was a mix of ozone, floor wax, and the hum of thirty CRT monitors. If you grew up in the 80s or 90s, you weren't just "playing" during school hours. You were surviving the Oregon Trail. You were hunting a thief across the globe. You were solving logic puzzles in a mansion owned by a guy who really liked muffins.

Honestly, old educational computer games were a weird anomaly. They were the only time "learning" felt like a genuine escape.

Most of these games shouldn't have worked. By modern standards, they’re clunky. The graphics are blocky. The sound is often a series of aggressive beeps. Yet, we still talk about them. We buy the t-shirts. We play the emulators. Why? It’s not just nostalgia. These games actually had something that many modern "edutainment" apps lack: stakes.

If you messed up in The Oregon Trail, your entire digital family died of dysentery. That stays with a kid. It wasn't a gold star or a "try again" screen. It was a cold, hard lesson in 19th-century reality.

The MECC Era and the Brutal Reality of the Trail

Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. That’s the mouthful of a name behind MECC. They were the titans. They didn't care about your feelings; they cared about history and resource management.

The Oregon Trail is the obvious king here. Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger created it in 1971 on a teletype machine. No screen. Just paper printouts. By the time it hit the Apple II, it became the definitive classroom experience. You had to choose your profession. Being a banker meant you had money, but being a carpenter or farmer meant you were actually useful when the wagon broke.

It taught us about trade-offs.

Do you push the oxen to "grueling" speed and risk a breakdown, or do you go slow and run out of food? This wasn't just math; it was a precursor to survival horror. People forget how bleak it was. You’d spend twenty minutes hunting deer—pressing the spacebar with surgical precision—only to realize you could only carry 200 pounds of meat back. The rest rotted. It was a lesson in waste that stayed with a generation.

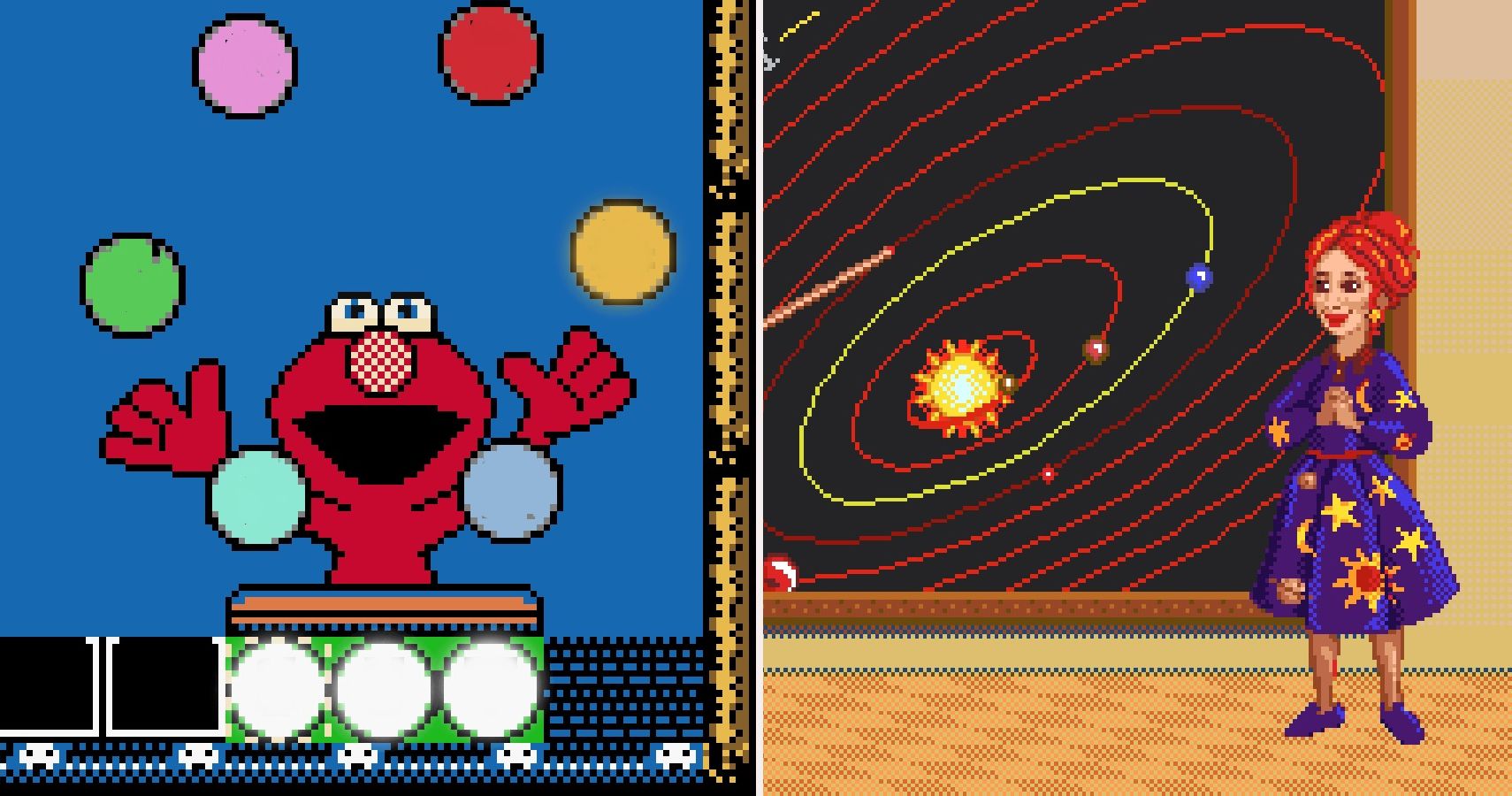

Then there was Number Munchers. Simple. Effective. You’re a green blob eating multiples of three while avoiding "Troggles." It was basically Pac-Man for people who wanted to pass third-grade math. The stress of a Troggle chasing you down while you frantically tried to remember if 54 was a multiple of 9 created a specific kind of mental fast-twitch fiber.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Every Bubbul Gem: Why the Map of Caves TOTK Actually Matters

Carmen Sandiego and the Art of the Manual

Brøderbund Software did something brilliant with Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? in 1985. They gave you a physical book.

If you bought the original game, it came with The World Almanac and Book of Facts. You couldn't just Google where the currency was the Baht. You had to actually flip through physical pages. This was the birth of "research-based" gaming. You weren't just guessing; you were an investigator.

The game worked because it treated the player like an adult. You had a deadline. You had a budget (your "acme" travel funds). If you flew to the wrong city, you wasted time. If the clock hit Monday morning and you hadn't caught the thief, the case was closed. Failure was an option.

We see a lot of modern educational apps that "gamify" learning by giving points for every click. Carmen Sandiego didn't do that. It made you work for the payoff. When that warrant finally issued and you heard the handcuffs click, it felt earned.

The Weird Brilliance of The Learning Company

While MECC was teaching us how to die in the wilderness, The Learning Company was getting weird.

Take The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis.

Released in 1996, this game was secretly a masterclass in set theory and algebraic logic. You had to move a group of small blue creatures across a map. The catch? Each Zoombini had different features: different eyes, noses, hair, and "feet" (skates, springs, etc.). To pass the Pizza Trolls, you had to deduce which combinations of toppings they liked through trial and error.

"Make me a pizza!"

🔗 Read more: Playing A Link to the Past Switch: Why It Still Hits Different Today

That voice still haunts people.

It wasn't teaching you 2+2. It was teaching you how to organize data. It was teaching you how to look at a group of objects and identify patterns. It was incredibly difficult. The "Oh, Rats!" level? Pure logistics.

Then you had Gizmos & Gadgets!. This was part of the Super Solvers series. You explored a warehouse, solved science puzzles to collect parts, and built a faster vehicle than the Master of Mischief. It taught physics—aerodynamics, gears, friction—without ever feeling like a textbook. You just wanted the better engine so you could win the race.

Humongous Entertainment and the Point-and-Click Revolution

We have to talk about Ron Gilbert. The man who gave us Monkey Island also co-founded Humongous Entertainment. This changed everything for the younger set.

Putt-Putt, Freddi Fish, Pajama Sam, and Spy Fox.

These games used the SCUMM engine (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion). They were high-quality adventure games. They didn't feel like "educational" software. They felt like interactive cartoons.

The "education" here was subtle. It was about problem-solving. Pajama Sam taught kids how to navigate "The Land of Darkness" by being brave and using logic. You needed a handle for a winch? You had to find the character who needed a specific item first. It was a chain of causality. It rewarded curiosity. Every screen had clickable "hotspots" that did nothing but play a funny animation. It encouraged kids to explore the digital space without fear of breaking something.

Why Modern Games Often Miss the Mark

There’s a tension in modern edutainment. Most of it is "chocolate-covered broccoli." The "game" part is a thin veneer over a boring quiz.

💡 You might also like: Plants vs Zombies Xbox One: Why Garden Warfare Still Slaps Years Later

Old educational computer games were different because the game was the learning.

In SimCity (the original 1989 version), you didn't take a quiz on urban planning. You just built a city and watched it burn because you put a coal plant next to a residential zone. The feedback loop was immediate and organic. You learned about taxes because if you set them too high, people moved out. You learned about infrastructure because if you didn't have power lines, nothing worked.

We’ve moved toward a model of "badges" and "streaks." These are psychological tricks to keep you clicking. But the old games? They relied on the inherent satisfaction of mastery.

The difficulty was real. Ever try to win Oregon Trail on the hardest setting? It’s nearly impossible. But that difficulty is what made the success mean something.

How to Revisit These Classics Today

If you’re looking to scratch that itch or show your kids what the fuss was about, you don't need a dusty Apple II in your garage.

- The Internet Archive: This is the "holy grail." Their MS-DOS library is massive. You can play The Oregon Trail, Prince of Persia, and Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? directly in your browser. It’s free and legal.

- GOG (Good Old Games): If you want a version that actually runs on Windows 11 without crashing, GOG sells "wrapped" versions of classics like the Humongous Entertainment collection.

- Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE): For the true historians, institutions like this keep the original hardware and software alive.

- Emulators: Tools like DOSBox allow you to run the original files if you can find the "abandonware" versions online.

The landscape of educational software has changed, but the lessons from the 80s and 90s are still valid. Good games don't talk down to players. They provide a set of rules, a clear goal, and the freedom to fail spectacularly.

To get the most out of these titles today, stop looking at them as historical curiosities. Treat them as puzzles. Don't look up the "correct" way to beat The Incredible Machine. Just start dragging pulleys and bowling balls onto the screen and see what happens. The joy wasn't in the "correct" answer; it was in the Rube Goldberg-esque chaos of getting there.

If you want to introduce these to a younger generation, start with Pajama Sam or Zoombinis. They hold up remarkably well because the art style is stylized and the logic puzzles are timeless. Skip the modern "remakes" if you can; the original pixel art has a charm that 3D renders often lose.

Go hunt some buffalo. Just remember: you can only carry 200 pounds back to the wagon.