March 1995 was a weird time for music. If you walked into a record store back then, the shelves were getting crowded with the aftermath of the "Wu-Tang takeover" strategy RZA had mapped out like a general. But nothing—honestly, nothing—prepared anyone for Return to the 36 Chambers: The Dirty Version. It wasn't just a solo debut. It was a 60-minute transmission from a mind that didn't seem to care about things like "on-beat rhyming" or "commercial viability."

Ol’ Dirty Bastard was the wild card. He was the specialist.

When people talk about this album today, they usually bring up the hit singles or the antics. But if you actually sit down and listen to the grit of the production, you realize it’s the most authentic bridge between the old-school park jams of the 70s and the gritty, paranoid basement sound of mid-90s Staten Island. It is messy. It is loud. It is occasionally out of tune. And that’s exactly why it works.

The Beautiful Mess of the Production

RZA was in his "First Cycle" prime during these sessions. We’re talking about the same era that birthed Liquid Swords and Only Built 4 Cuban Linx..., but those albums had a cinematic, polished darkness. Return to the 36 Chambers feels like it was recorded in a room with a leaky pipe and a blown-out speaker.

Take "Shimmy Shimmy Ya." It is arguably one of the most recognizable piano loops in history. But listen to the way the drums hit. They aren't clean. They’re dusty. They sound like they were sampled off a vinyl that had been used as a coaster for a year. That was the magic of the Wu-Tang sound at its peak—the "dirt" wasn't a filter; it was the environment.

The sessions at 36 Chambers Studio were legendary for being chaotic. While Method Man was becoming a superstar and GZA was crafting chess-inspired metaphors, ODB—born Russell Jones—was just being himself. He’d show up late, sing off-key, and bark like a dog. RZA had the impossible task of turning those outbursts into songs. He didn't try to polish ODB. He built the tracks around the madness.

Why the Vocals Still Confuse People

Is he rapping? Is he singing? Is he just yelling?

📖 Related: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Yes.

On tracks like "Brooklyn Zoo," the energy is terrifying. He starts the verse with a level of intensity that most rappers save for their climax. By the time he gets halfway through, he's basically snarling. There is no "flow" in the traditional sense. It’s a rhythmic assault. Most critics at the time didn't know what to do with it. Some called it "novelty," but they missed the point. ODB was channeling the spirit of the old-school "human beatbox" and the spontaneity of 1970s soul singers like James Brown or Wilson Pickett.

The track "Drunk Game (Sweet 69)" is a perfect example of his "style." It’s an R&B parody that isn't actually a parody. He’s singing his heart out, and he’s completely flat. He’s howling. It’s uncomfortable to listen to in a crowded room. But it’s also incredibly brave. Nobody else in hip-hop had the confidence to be that vulnerable—and that ridiculous—at the same time.

The Guest List and the Family Dynamic

Even though this is a solo album, the Wu-Tang Clan presence is everywhere. But it feels different here than on other solo projects. On Raekwon’s album, the guests feel like co-stars in a movie. On Return to the 36 Chambers, the guests feel like they are just trying to keep up with the main character.

Raekwon and Method Man show up on "Raw Hide," and they bring that classic Shaolin sharpness. But then ODB comes back in, and the whole vibe shifts back to the erratic. Ghostface Killah pops up on "Baby C-Come On," and you can hear the chemistry. These guys weren't just label mates; they were family who grew up watching ODB be the funniest guy in the room. They respected his "Drunken Monk" style because it was impossible to replicate.

Key Contributors Who Made the Sound:

- RZA: The architect who managed to find the rhythm in ODB's stutters.

- Buddah Monk: A crucial part of ODB’s "Brooklyn Zu" circle who helped maintain the energy.

- 4th Disciple: Provided additional production that kept the sonic aesthetic consistent with the Wu-Tang brand.

The Cultural Impact Nobody Saw Coming

You have to remember that in 1995, hip-hop was starting to get "shiny." Puffy and the Bad Boy era were beginning to rise. Everything was getting smoother, more melodic, and much more expensive-looking.

👉 See also: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

Then came ODB.

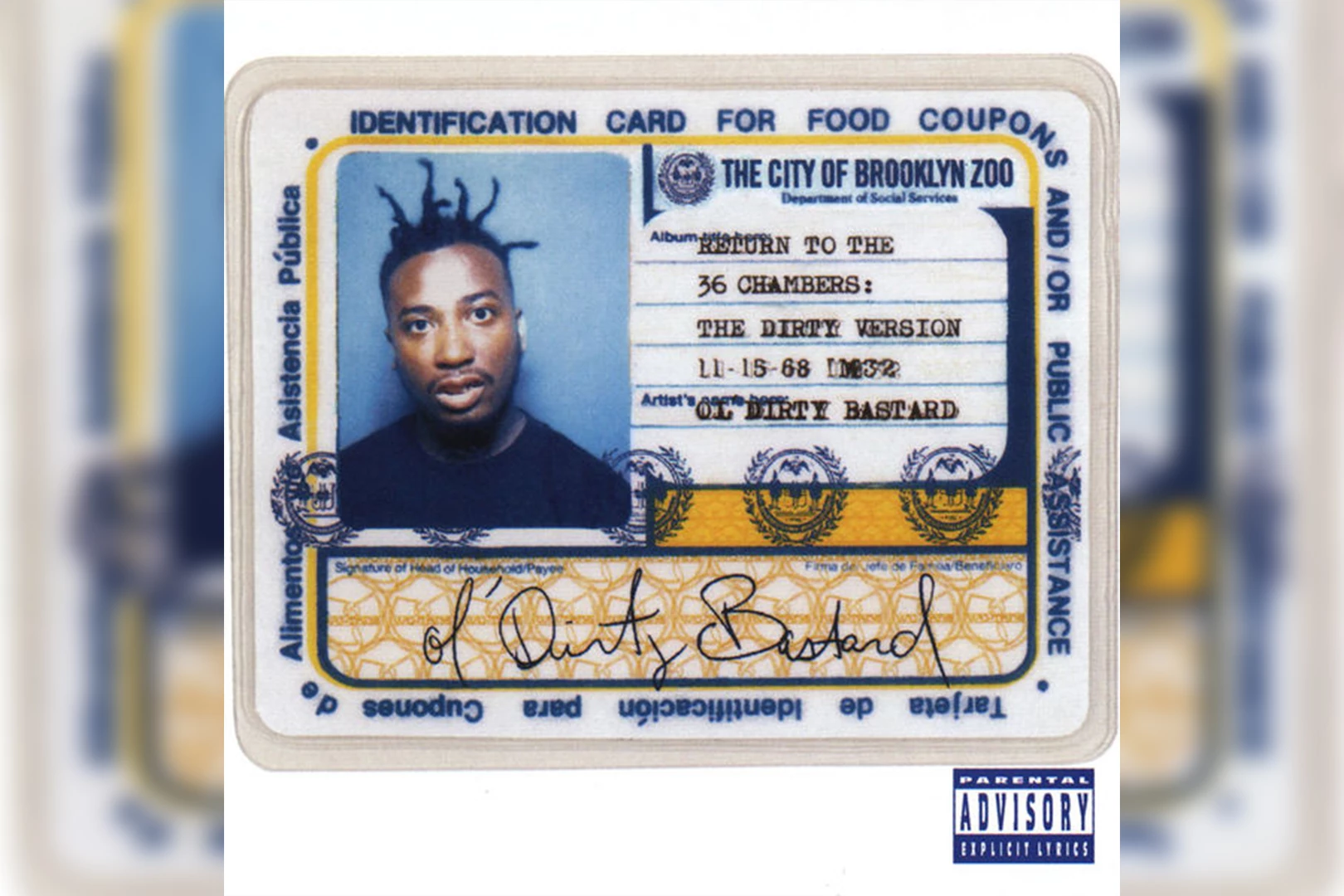

The cover of Return to the 36 Chambers is a parody of a Public Assistance ID card. Think about that for a second. While other rappers were posing in front of private jets, Dirty was putting his food stamps front and center. It was a massive "f-you" to the growing commercialization of the genre. He was representing the people who were actually living in the projects, not the people who were trying to escape them.

This authenticity is why he became a folk hero. When he took a limousine to go pick up his welfare check with an MTV news crew in tow, it wasn't just a stunt. It was performance art. He was highlighting the absurdity of the system. The album is the soundtrack to that mindset—unfiltered, unapologetic, and deeply rooted in the reality of the struggle.

Misconceptions About the "Dirty Version"

A lot of people think "The Dirty Version" just refers to explicit lyrics. It doesn't. In the context of this album, "dirty" is an aesthetic. It’s a philosophy. It means raw. It means unrefined. It means the version of the song before the lawyers and the radio programmers get their hands on it.

There’s also this weird myth that ODB didn't write his lyrics. While it’s true that GZA and RZA helped him structure some of his ideas—and RZA famously wrote the hook for "Shimmy Shimmy Ya"—the delivery and the "vibe" were 100% Russell Jones. You can't write "Dirt Dog." You can't script the way he pauses or the way he suddenly switches into a high-pitched squeal.

The album also gets labeled as a comedy record far too often. Sure, it’s funny. ODB was hilarious. But tracks like "Cuttin' Headz" (featuring RZA) show off some of the most technical, rapid-fire rapping of the decade. The humor was just a layer. Underneath it was a serious obsession with the craft of the "MC" as an entertainer.

✨ Don't miss: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

The Legacy of the 36 Chambers Today

If you listen to modern "SoundCloud rap" or the experimental fringe of the underground, you can hear ODB’s DNA everywhere. Danny Brown’s high-pitched delivery? That’s ODB. Tyler, The Creator’s early persona? That’s ODB. Anyone who chooses personality over "perfect" technique owes a debt to this record.

Return to the 36 Chambers proved that you didn't have to be the best "technical" rapper to make a masterpiece. You just had to be the most interesting person in the booth. It remains the most unique entry in the Wu-Tang solo catalog because it’s the only one that feels like it could fall apart at any second. And yet, 30 years later, it’s still standing perfectly still.

How to Truly Appreciate the Album Now

If you want to dive back into this, don't just put on a "Best of Wu-Tang" playlist. You need the full experience.

- Find the Original Mastering: If you can, listen to an older press or a high-quality lossless version. The modern digital remasters sometimes try to "clean up" the noise, which is exactly what you don't want. You want to hear the hiss.

- Listen with Headphones: RZA’s panning on this album is underrated. He moves voices and sounds around the stereo field in a way that makes you feel like you’re sitting in the middle of a chaotic cipher.

- Read the Liner Notes: The credits are a who's who of the mid-90s New York underground.

- Watch the Videos: "Brooklyn Zoo" and "Shimmy Shimmy Ya" are essential visual companions. They capture the kinetic, unpredictable energy that defined ODB's physical presence.

The best way to honor the legacy of this record is to stop looking for the "logic" in it. It isn't a logical album. It’s an emotional one. It’s the sound of a man who was given a microphone and told he could do whatever he wanted, and for one brief, shining moment in 1995, he actually did.

The "Dirty Version" isn't just a title; it's a badge of honor. In a world of AI-generated hooks and perfectly tuned vocals, we need that dirt more than ever. It’s the only thing that feels real.

Go back. Listen to the opening track. Listen to him tell you that there is no father to his style. He wasn't lying. There wasn't then, and there isn't now.

Next Steps for Hip-Hop Heads:

Start by revisiting the "Brooklyn Zoo" music video to see the raw intensity ODB brought to his debut. Then, compare the production on this album to RZA’s work on GZA’s Liquid Swords (released the same year) to see how RZA tailored his "grime" specifically for Dirty’s voice. Finally, track down the 25th Anniversary Deluxe Edition—it contains several instrumentals and a cappella versions that reveal just how complex these "messy" songs actually were.