You’re sitting in a waiting room, or maybe you’re scrolling through your phone, and you see that familiar, flashing red alert from the Red Cross. "Urgent Need." It feels constant. You might wonder if they’re just being dramatic or if there is a specific reason why the notifications never seem to stop. Honestly, it comes down to a math problem that hospitals can’t ever quite solve. When people ask what blood type is needed the most, the answer is almost always O negative, but the "why" behind that is a mix of biology, emergency room chaos, and some pretty stark population statistics.

Blood isn't just blood. It’s a complex soup of antigens and antibodies. If you get the wrong kind, your immune system treats it like an invasive parasite. It attacks. That attack can be fatal.

The Universal Donor Burden

The reason O negative tops the list is simple: it is the "universal" type. In a trauma bay, when a helicopter lands and a patient is bleeding out from a car wreck, doctors don't have twenty minutes to wait for a lab to cross-match a blood sample. They need to hang a bag now. O negative blood lacks the A, B, and Rh antigens. Because it’s "naked," so to speak, almost anyone can receive it without their body freaking out.

It’s the gold standard for emergencies.

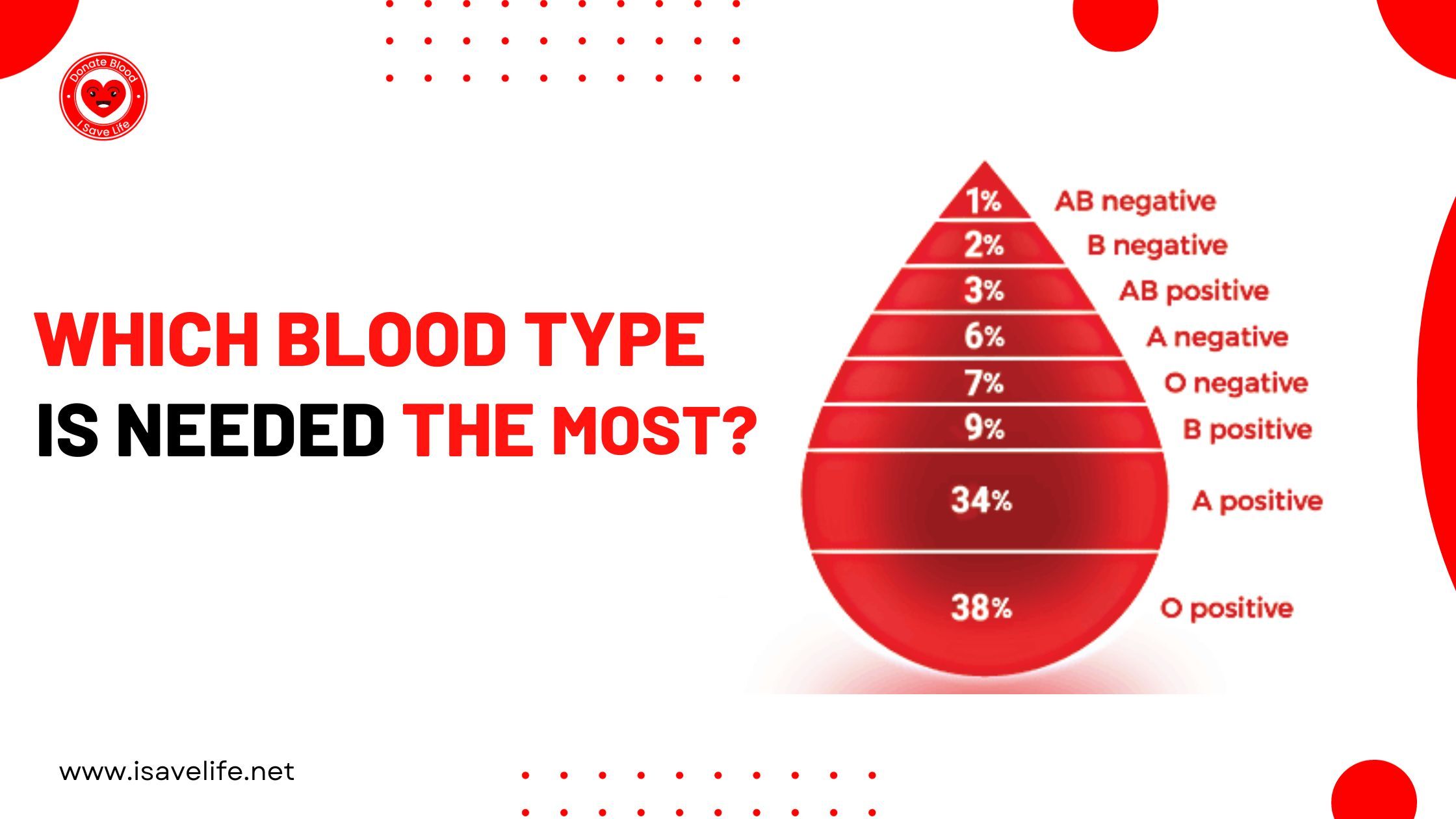

But here is the kicker. Only about 7% of the population has O negative blood. Imagine a grocery store where everyone wants the same specific brand of milk, but the delivery truck only brings three cartons a week. That is the constant state of the American blood supply. Hospitals use O negative at a rate far higher than the percentage of people who actually have it.

What about O Positive?

While O negative is the emergency room darling, O positive is actually the most common blood type in the world. Roughly 38% of people have it. Because so many people are O positive, there is a massive, constant demand for it just to keep up with routine surgeries and cancer treatments. If you are O positive, you can give to anyone with a positive blood type (A+, B+, AB+, or O+). Since about 80% of the population has a positive blood type, your O positive donation is incredibly versatile.

It’s the workhorse. While O negative is the "break glass in case of emergency" option, O positive keeps the hospital lights on.

👉 See also: Lake Point Recovery and Wellness: What Actually Happens During Rural Rehab

Why the "Most Needed" Title Shifts

Sometimes you’ll see a call for Platelets or Type B. It’s not a mistake. Blood has a shelf life. It’s not like a can of soup that sits in the pantry for five years. Whole blood usually lasts around 42 days. Platelets? They only last five. That is a logistical nightmare.

If a city has a massive influx of Type A donors one week, they might be set for a month. But if three people with a rare subtype come into the ICU the following Tuesday, the inventory vanishes.

Dr. Pampee Young, the Chief Medical Officer of the American Red Cross, often points out that blood shortages are local and seasonal. In the winter, flu outbreaks keep donors home. In the summer, people are on vacation and forget to stop by the center. This creates "valleys" in the supply where what blood type is needed the most changes based on whoever isn't showing up that week.

The AB Plasma Paradox

We talk a lot about red cells, but plasma is the other half of the story. Interestingly, the rules for plasma are flipped. Type AB is the universal plasma donor. While AB negative is the rarest blood type in the U.S. (around 1%), their plasma can be given to anyone in an emergency.

If you are AB, your red cells are only useful to other AB patients, but your plasma is liquid gold. Hospitals use it for burn victims, shock, and massive clotting issues.

The Rare Type Struggle

We can't talk about demand without talking about diversity. Genetics determine blood type. This means that certain rare blood types are found almost exclusively in specific ethnic groups.

Take the Ro subtype, for example. It is frequently found in individuals of African descent. For patients with Sickle Cell Disease—who require frequent, life-saving transfusions—finding a precise match is critical. If they receive blood that is "close enough" but not a perfect match, they can develop antibodies that make future transfusions nearly impossible.

In these cases, the "most needed" blood isn't just about O negative; it's about finding a donor whose genetic background matches the patient's. This is why medical experts like those at America’s Blood Centers emphasize that a diverse donor pool is just as important as a large one.

Misconceptions That Keep People Away

A lot of people think they can't give blood because they have tattoos, or they traveled to Europe in the 90s, or they are on medication. Most of those rules have changed.

- Tattoos: In most states, if you got your ink in a licensed shop, there’s no waiting period.

- The "Mad Cow" Ban: The FDA recently lifted the long-standing deferral for people who lived in the UK or Europe during certain years. Thousands of people are now eligible who weren't two years ago.

- Diabetes and Meds: As long as your condition is managed and you’re feeling well, you’re usually good to go.

Fear of needles is real. It sucks. But the actual "pinch" lasts about three seconds. The actual donation takes maybe ten minutes. You spend more time picking out which flavor of juice and cookies you want afterward.

The Reality of the "Shortage"

When a news anchor says there is a "national blood shortage," they aren't talking about a total lack of blood. They are talking about the "days on hand."

A healthy blood supply is about a five-day surplus. Most of the time, the U.S. is hovering around a two-day supply. Sometimes, for O negative, it drops to less than half a day. When it gets that low, hospitals have to start making hard choices. They might postpone an elective heart surgery because they need to save their last three bags of O negative for a potential gunshot victim or a complication in the labor and delivery ward.

That is the hidden cost of the shortage. It isn't just about the people who don't get blood; it's about the medical system slowing down because doctors are afraid to run out.

Actionable Steps for Potential Donors

If you’re wondering where you fit into this, the first step isn't even necessarily donating. It’s knowing.

Find out your type. If you don't know your blood type, the easiest way to find out is to donate. They will mail you a card or update your app with your type within a week. It’s free, and you’re helping someone.

✨ Don't miss: Foods Containing Manganese: What Most People Get Wrong About This Trace Mineral

Target your donation. If you find out you are O negative or O positive, consider doing a "Power Red" donation. This uses a machine to take two units of red cells while returning your plasma and platelets to you. It doubles your impact for the types that are in highest demand.

Be the "Holiday Donor." The weeks between Christmas and New Year’s, and the week of July 4th, are historically the lowest points for blood collection. If you want to be the person who fills the biggest gap, schedule your appointments during these "dead zones."

Track the need. The Red Cross Blood Donor app is actually pretty high-tech. It tracks your blood as it moves through the system. You’ll get a notification saying your blood was sent to a specific hospital in a specific city. Seeing that your "Type O" actually arrived at a trauma center three counties away makes the whole process feel much more real.

The question of what blood type is needed the most isn't just a trivia point. It’s a fluctuating reflection of who is in the hospital right now. While O negative will always be the "universal" priority, the truth is that the most needed blood is whichever type is currently missing from the shelf when a patient needs it. Every type has a "universal" application in its own way—whether it's AB plasma for a burn victim or O positive for a surgery patient.

Sign up. Show up. It’s one of the few things you can do that has a direct, measurable impact on whether someone else gets to go home.