It happened in 2000. A weird, sepia-toned movie about three escaped convicts in the Deep South hit theaters, and suddenly, everyone was obsessed with bluegrass. People weren't just watching George Clooney lip-sync; they were buying the soundtrack in droves. We’re talking about eight million copies sold. That’s staggering for a collection of "old-timey" music that most record executives thought would be a niche hobbyist project at best. The O Brother Where Art Thou songs didn't just provide a backdrop for the Coen Brothers’ Odyssey-inspired romp; they fundamentally shifted how modern audiences engage with American folk, gospel, and blues.

If you were around then, you remember. "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow" was everywhere. It was on the radio between boy bands and post-grunge acts. It won a Grammy for Best Country Collaboration, while the album itself took home Album of the Year, beating out OutKast and U2. Think about that for a second. A collection of songs rooted in the 1920s and 30s dominated the turn of the millennium. It wasn't because of some high-tech production or a flashy marketing campaign. It worked because the music felt ancient and brand new at the same time.

The Secret Architect: T Bone Burnett’s Vision

Most people credit the Coen Brothers for the film’s vibe, but when it comes to the O Brother Where Art Thou songs, the real genius is T Bone Burnett. He didn't just pick some cool tunes. He curated a sonic landscape that existed before the movie was even shot. In fact, the actors had to choreograph their scenes to the pre-recorded tracks. This is rare. Usually, the score comes last. Here, the music was the script.

Burnett dug deep into the archives of Alan Lomax and Harry Smith. He wanted dirt. He wanted the grit of the Great Depression. He brought in heavy hitters like Alison Krauss, Gillian Welch, and Ralph Stanley. If you listen closely to "O Death," performed a cappella by Stanley, you can hear the actual history of the Appalachians in his voice. It’s chilling. Stanley was in his 70s when he recorded that, and his shaky, haunting delivery won him a Grammy. It’s a far cry from the polished, over-produced country music coming out of Nashville at the time.

Honestly, the soundtrack’s success was a huge middle finger to the industry’s obsession with "radio-friendly" hits. It proved that authenticity has a massive market. People were hungry for something that felt like it had dirt under its fingernails.

That Soggy Bottom Boys Magic

Let’s talk about "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow." Most people know the George Clooney version—or rather, the version where Dan Tyminski provides the voice for Clooney’s character, Everett McGill. Tyminski, a member of Alison Krauss’s band Union Station, has a voice that sounds like polished wood and rusted iron.

🔗 Read more: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

The song itself isn't new. Not even close. It was first published by Dick Burnett (no relation to T Bone) around 1913. It had been covered by Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and The Stanley Brothers decades before the movie. But the Soggy Bottom Boys' arrangement gave it a driving, rhythmic urgency that felt contemporary. It’s a song about wandering, exile, and the hope of a better world—themes that are pretty much universal.

Interestingly, Dan Tyminski’s wife reportedly didn't think much of the recording when he first played it for her. He went home and told her he’d recorded this old song for a movie, and she basically shrugged. Then it became a multi-platinum sensation. It just goes to show that even the people making the music sometimes have no clue when they’re sitting on a cultural earthquake.

The Women Who Stole the Show

While the Soggy Bottom Boys got the glory, the women on the soundtrack provided the soul. Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, and Gillian Welch harmonizing on "Didn't Leave Nobody but the Baby" is haunting. It’s a lullaby, sure, but it sounds like something whispered in a graveyard.

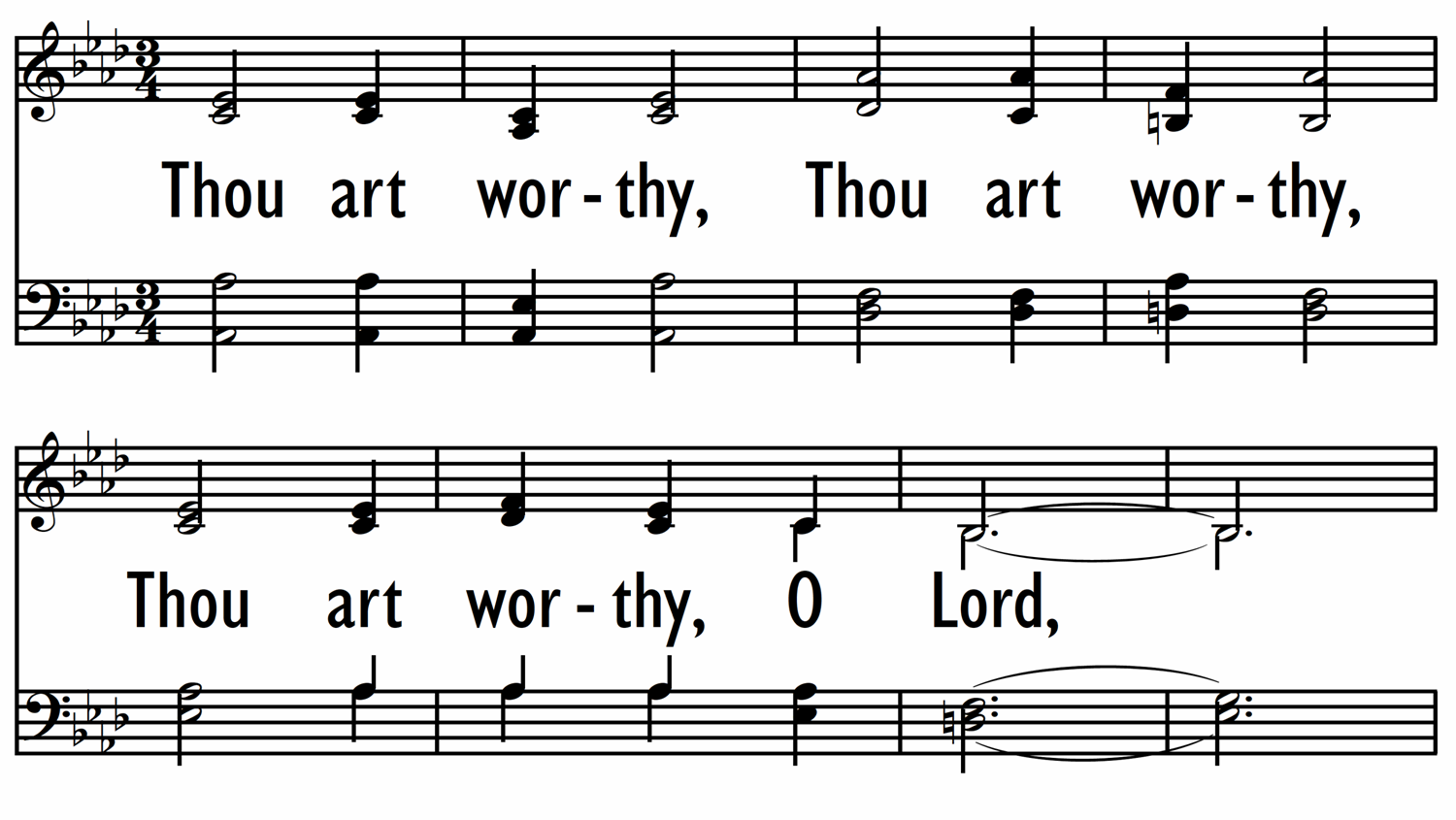

Then you have "Down to the River to Pray." Alison Krauss leads this gospel track with a clarity that feels almost supernatural. It’s a simple song. It’s repetitive. But in the context of the film’s baptism scene, it becomes an anthem of transformation. It’s one of those O Brother Where Art Thou songs that people still sing in choirs and at weddings today. It transcended the film entirely.

Gospel, Blues, and the Chain Gang

The album opens with "Po' Lazarus," a genuine chain gang song. This isn't a studio recreation. It’s a 1959 field recording made by Alan Lomax at the Mississippi State Penitentiary. The lead singer was an actual inmate named James Carter.

💡 You might also like: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

When the soundtrack became a hit, T Bone Burnett actually went looking for Carter to pay him his royalties. He eventually found him living in Chicago, long retired from his days on the chain gang. Carter didn't even remember the recording. He was handed a check for $20,000 and a platinum record. That’s a real-life "O Brother" moment right there. It anchors the whole project in a reality that you just can't fake in a recording booth in Burbank.

The variety on the record is wild. You go from the upbeat, almost frantic "Keep on the Sunny Side" by The Whites to the dark, bluesy "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues" by Chris Thomas King. King, who played the character Tommy Johnson in the film, actually performed his track live on set. No overdubs. Just a man and a guitar. It captures that raw, Delta blues energy that usually gets lost in modern digital recording.

Why These Songs Still Matter in 2026

You might wonder why we’re still talking about this twenty-five years later. It’s simple: the O Brother Where Art Thou songs acted as a bridge. Before this album, bluegrass and "old-time" music were relegated to tiny festivals and niche radio stations. After O Brother, we saw the rise of the "Americana" genre.

Without this soundtrack, do we get Mumford & Sons? Probably not. Do we get the massive resurgence of the banjo in indie rock? Unlikely. It gave younger generations permission to look backward for inspiration. It showed that you could take 100-year-old music and make it the coolest thing in the room.

The legacy of the music also lives on in the "Down from the Mountain" concert tour that followed the movie. It was a documentary and a tour that brought these legendary folk artists to massive arenas. For many of them, like Ralph Stanley or the Peavey family, it was the biggest payday and the widest recognition of their entire careers. It was a victory lap for a style of music that the world had tried to forget.

📖 Related: Cómo salvar a tu favorito: La verdad sobre la votación de La Casa de los Famosos Colombia

Common Misconceptions About the Music

- George Clooney sang his parts: Nope. As mentioned, that's Dan Tyminski. Clooney reportedly practiced hard, but when he stepped up to the mic, he realized he couldn't quite hit that high-lonesome bluegrass twang. He’s been very open about being outclassed by the pros.

- It’s all Bluegrass: Actually, it’s a mix. There’s Southern Gospel, Delta Blues, Country, and A Cappella Folk. Labeling it just "bluegrass" ignores the deep African American influence found in the blues and chain gang tracks.

- The songs were written for the movie: Most were traditional songs or covers of mid-century hits. Only a few arrangements were "new" for the film.

How to Explore This Sound Yourself

If you’re just getting into the O Brother Where Art Thou songs, don't stop at the soundtrack. Use it as a roadmap. If you loved the Soggy Bottom Boys, go listen to The Stanley Brothers or Bill Monroe. If "Down to the River to Pray" moved you, dig into the archives of the Fairfield Four.

The real magic of this music is that it’s participatory. These aren't songs meant to be kept behind glass. They were meant to be sung on porches, in churches, and while working.

To really appreciate the depth of this genre, start by looking up the "Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music." It’s the "Old Testament" for the sounds you hear in the movie. You'll find the weird, dark, and beautiful roots that T Bone Burnett drew from. Also, check out the work of Norman Blake, the master guitarist who played on much of the O Brother soundtrack but rarely gets the spotlight he deserves. His flatpicking technique is the gold standard in the acoustic world.

The music of O Brother, Where Art Thou? isn't a museum piece. It’s a living, breathing tradition. Even now, in a world dominated by AI-generated beats and hyper-processed vocals, there’s something about a single voice and a wooden instrument that cuts through the noise. It’s honest. It’s human. And that’s why we’re still listening.

Actionable Steps for Music Lovers

- Create a "Roots" Playlist: Start with the O Brother soundtrack, but add "Will the Circle Be Unbroken" by the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and anything by Doc Watson.

- Learn the History: Read The Land Where the Blues Began by Alan Lomax. It gives context to the "Po' Lazarus" style of field recordings.

- Support Local Bluegrass: Look for local jams in your area. This music is best experienced live and loud in a small room, not just through headphones.

- Instrument Exploration: If you've ever wanted to pick up a mandolin or a banjo, there has never been a better time. Online resources for "old-time" playing styles have exploded because of the interest this film initially sparked.

The impact of these songs is undeniable. They reminded us that our musical heritage is rich, complicated, and incredibly beautiful. Whether you're a casual listener or a die-hard folkie, the soundtrack remains a vital touchstone in American culture. Dig back into those tracks today and you'll likely hear something you missed the first time around.