Roger Thornhill isn't a spy. He’s just a guy who wants a drink and a taxi. But in the world of North by Northwest Alfred Hitchcock created, being an advertising executive is apparently enough to get you marked for death by a shadowy cabal of international villains. Honestly, that’s the genius of it. Hitchcock didn't want to make a gritty documentary about espionage. He wanted to make a "picture to end all pictures," and sixty-odd years later, most of Hollywood is still trying to catch up to what he pulled off in 1959.

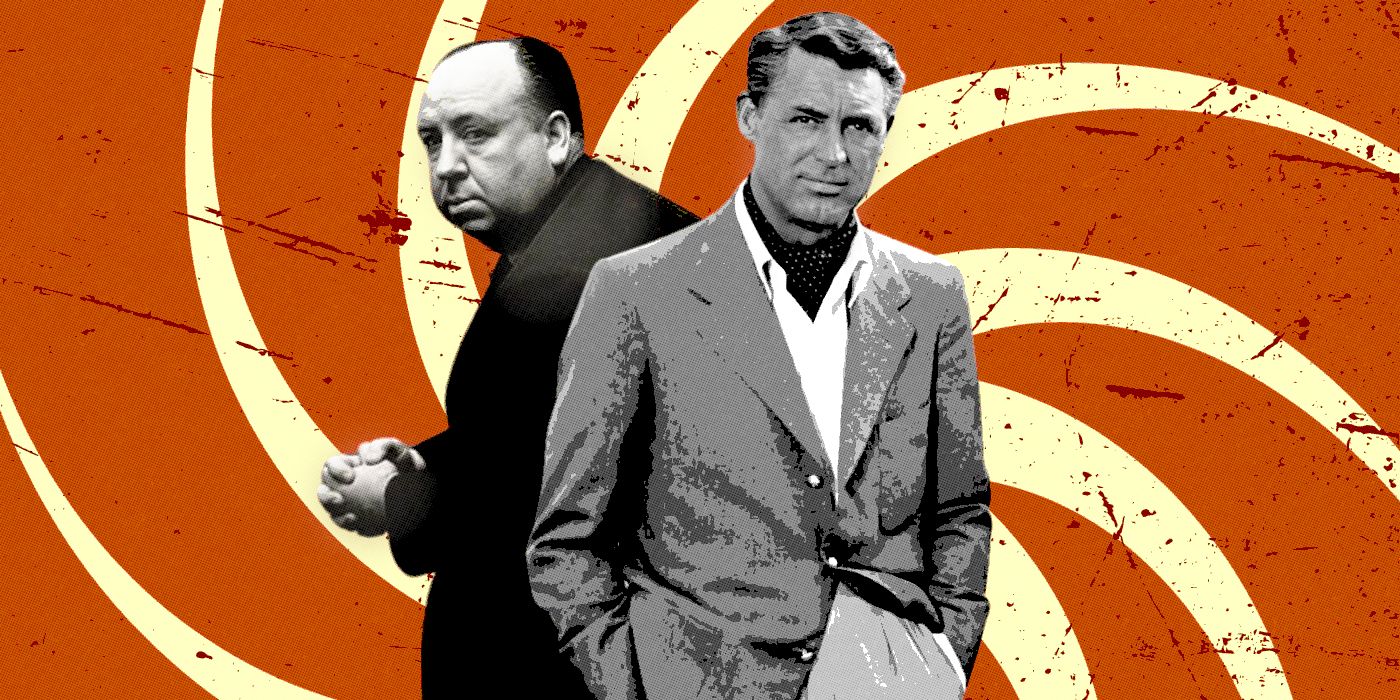

It’s the quintessential "wrong man" story. Cary Grant plays Thornhill with this breezy, scotch-sipping arrogance that makes his eventual descent into chaos feel both hilarious and terrifying. When he’s kidnapped from the Plaza Hotel because some guy named George Kaplan didn't answer a page, the gears of the greatest chase movie ever made start turning. It’s fast. It’s witty. It’s kind of ridiculous if you think about it too hard, but Hitchcock never gives you the time to think. He just keeps the camera moving.

The Crop Duster Scene is Basically a Masterclass in Anxiety

You’ve seen the shot. Even if you’ve never watched the full movie, you know the one where Cary Grant is running away from a biplane in a cornfield. Most directors would have put him in a dark alley with a bunch of guys in trench coats. That’s the cliché. Hitchcock did the opposite. He put his hero in a wide-open space in broad daylight where there is absolutely nowhere to hide.

There’s no music. For nearly seven minutes, the only thing you hear is the wind and the distant hum of an engine. It’s agonizing. Hitchcock once told François Truffaut in their famous series of interviews that he wanted to see if he could create suspense with nothing but "the sun and a flat landscape." He proved that silence is way scarier than a loud orchestra. When that plane finally dives, and the dust starts kicking up, it’s a visceral shock. It’s not just an action beat; it’s a nightmare realized in 35mm.

The logistics of that shoot were a total nightmare, too. They filmed in Wasco, California, and the heat was brutal. Grant, being the professional he was, supposedly worried about his suit getting ruined more than the plane. But that suit—a grey, ventless, three-button number from Kilgour, French & Stanbury—has become as iconic as the scene itself. It’s been voted the best suit in film history more times than I can count.

Writing a Script While Moving the Camera

Ernest Lehman, the screenwriter, basically set out to write the ultimate Hitchcock film. He and "Hitch" would sit together and just throw out set pieces they wanted to see. Hitchcock wanted a chase across Mount Rushmore. He wanted a murder at the United Nations. Lehman had to figure out how to glue those together.

It’s a miracle it works. Usually, when you write a script based on "cool locations," it feels disjointed. But the dialogue here is sharp as a razor. Take the train scene between Thornhill and Eve Kendall (played by Eva Marie Saint). It’s incredibly suggestive for 1959. The double entendres are flying so fast you almost miss the fact that they’re basically talking about sex the entire time. "I never discuss love on an empty stomach," she says. "You've already eaten," he replies. It’s smooth. It’s adult. It makes modern action movie dialogue sound like it was written by a toddler.

✨ Don't miss: Carrie Bradshaw apt NYC: Why Fans Still Flock to Perry Street

Why Mount Rushmore Almost Didn't Happen

The climax of North by Northwest Alfred Hitchcock is legendary, but the National Park Service was not thrilled about it. At all. They gave permission to film at the monument on the condition that no violence would be shown on the faces of the Presidents. They felt it was disrespectful.

Hitchcock, being Hitchcock, tried to push his luck. He originally wanted a scene where Cary Grant hides in Lincoln’s nose and has a sneezing fit that gives him away. The authorities said absolutely not. They actually revoked the filming permit halfway through because of the "sacrilegious" nature of the mock-ups. Most of that final chase was actually filmed on a massive, terrifyingly realistic set back in Culver City.

The scaling of those faces—Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln—is eerie. Watching James Mason’s henchman, Leonard (played by a young, chilling Martin Landau), step on Thornhill’s fingers as he dangles over the edge is pure cinema. It’s a literal cliffhanger. It’s also one of the first times we see a villain who is clearly, albeit subtly, coded as gay, which added a whole other layer of tension to the dynamics between the antagonists.

The MacGuffin and the Art of Nothing

Hitchcock loved his "MacGuffins." This is the thing the characters are all chasing that the audience doesn't really care about. In this movie, it’s "government secrets" hidden in a piece of pre-Columbian statuary. What secrets? It doesn't matter. It could be a sourdough starter recipe for all the plot cares.

By making the stakes so vague, Hitchcock forces you to focus on the characters. You care about whether Thornhill survives and whether Eve is actually a double agent or just a femme fatale. You’re invested in the romance, not the microfilm. This is where modern "franchise" movies fail. They spend forty minutes explaining the lore of the "Cosmic Cube" or whatever, and they forget to make us like the people holding it.

Technical Brilliance You Might Miss

The cinematography by Robert Burks is lush. This was filmed in VistaVision, which was Paramount’s high-resolution answer to CinemaScope. It’s why the colors pop so much even today. The reds in the dining car, the deep blues of the forest—it looks like a moving painting.

🔗 Read more: Brother May I Have Some Oats Script: Why This Bizarre Pig Meme Refuses to Die

And we have to talk about Saul Bass. The opening credits are revolutionary. Those kinetic, intersecting lines that turn into the facade of a skyscraper? That was the first time a movie used kinetic typography. It sets the tone immediately: this is a world of grids, traps, and shifting perspectives.

Then there’s Bernard Herrmann’s score. Instead of a standard "suspense" theme, he wrote an overture that sounds like a frantic fandango. It’s rhythmic and driving. It tells you from the first frame that this is going to be a wild ride. Herrmann and Hitchcock were the perfect duo until they famously fell out during Torn Curtain, but here, they are in total sync.

Common Misconceptions About the Production

Some people think the movie was a massive hit that everyone loved immediately. While it did well, some critics at the time thought it was "frivolous." They wanted Hitchcock to keep making "serious" psychological thrillers like Vertigo, which had come out the year before and initially flopped.

- Myth: The crop duster scene used a real crash.

- Reality: The crash into the fuel truck was a mix of a real plane and a very convincing mock-up.

- Myth: Cary Grant and Hitchcock got along perfectly.

- Reality: Grant famously complained during filming that he didn't understand what was happening in the script. Hitchcock loved that, because the character wasn't supposed to know what was happening either.

- Fact: The final shot of the train entering the tunnel is one of the most famous sexual metaphors in film history. The censors let it slide, probably because it was too clever to ban.

The Legacy of the Master

When people talk about North by Northwest Alfred Hitchcock, they often call it the "first James Bond movie." It’s easy to see why. You’ve got the globe-trotting locations, the sophisticated villain, the gadget-adjacent plot points, and the invincible, charming hero. Without this film, Sean Connery probably wouldn't have had a template for 007.

But it’s more than just a blueprint for Bond. It’s a movie about identity. Roger Thornhill spends the whole movie trying to prove he’s not George Kaplan, only to eventually realize that to save the girl, he has to become George Kaplan. It’s a weirdly deep theme for a movie that features a man being chased by a plane.

It’s also surprisingly funny. The scene where Thornhill acts "crazy" at an auction to get the police to arrest him is a masterclass in comedic timing. Grant's "I'm being obnoxious so you'll take me away" bit is genuinely hilarious. It balances the life-or-death stakes with a sense of playfulness that you just don't see in the "grimdark" action movies of the 2020s.

💡 You might also like: Brokeback Mountain Gay Scene: What Most People Get Wrong

How to Experience the Film Today

If you’re going to watch it, find the 4K restoration. The detail is staggering. You can see the texture of the rock on Mount Rushmore and the sweat on Cary Grant’s brow. It’s a reminder of what "big" movies used to look like before everything was replaced by green screens and CGI.

Next Steps for Film Lovers:

First, watch the film with the sound off for ten minutes. You’ll notice how Hitchcock tells the story purely through visual cues and character blocking. It’s a great way to see how "pure cinema" works.

Second, compare the crop duster scene to the "chase" scenes in modern blockbusters. Look at the pacing. Notice how much time Hitchcock spends building the threat before the first shot is even fired.

Finally, check out the 1966 film Charade. It’s often called "the best Hitchcock movie Hitchcock never made," and it stars Cary Grant in a very similar vibe. If you liked the wit and the "wrong man" tropes of the 1959 classic, that’s your next logical stop.

There’s a reason we’re still talking about this movie. It’s not just "old movie" nostalgia. It’s because Hitchcock understood that a movie is a machine designed to make the audience feel something. Whether it’s the vertigo of a heights-based climax or the confusion of a mistaken identity, he knew how to pull the levers. North by Northwest Alfred Hitchcock remains the gold standard for how to make an audience sweat while they’re smiling.