It starts with a checkbook and ends with a cold shoulder. If you’ve ever felt the sudden, chilling silence of a phone that stops ringing the second your luck runs out, you aren't alone. You're actually participating in a century-old blues tradition. Nobody knows you when you're down isn't just a cynical observation; it’s a blueprint of human social dynamics that has stayed relevant from the Great Depression to the era of viral "clout chasing."

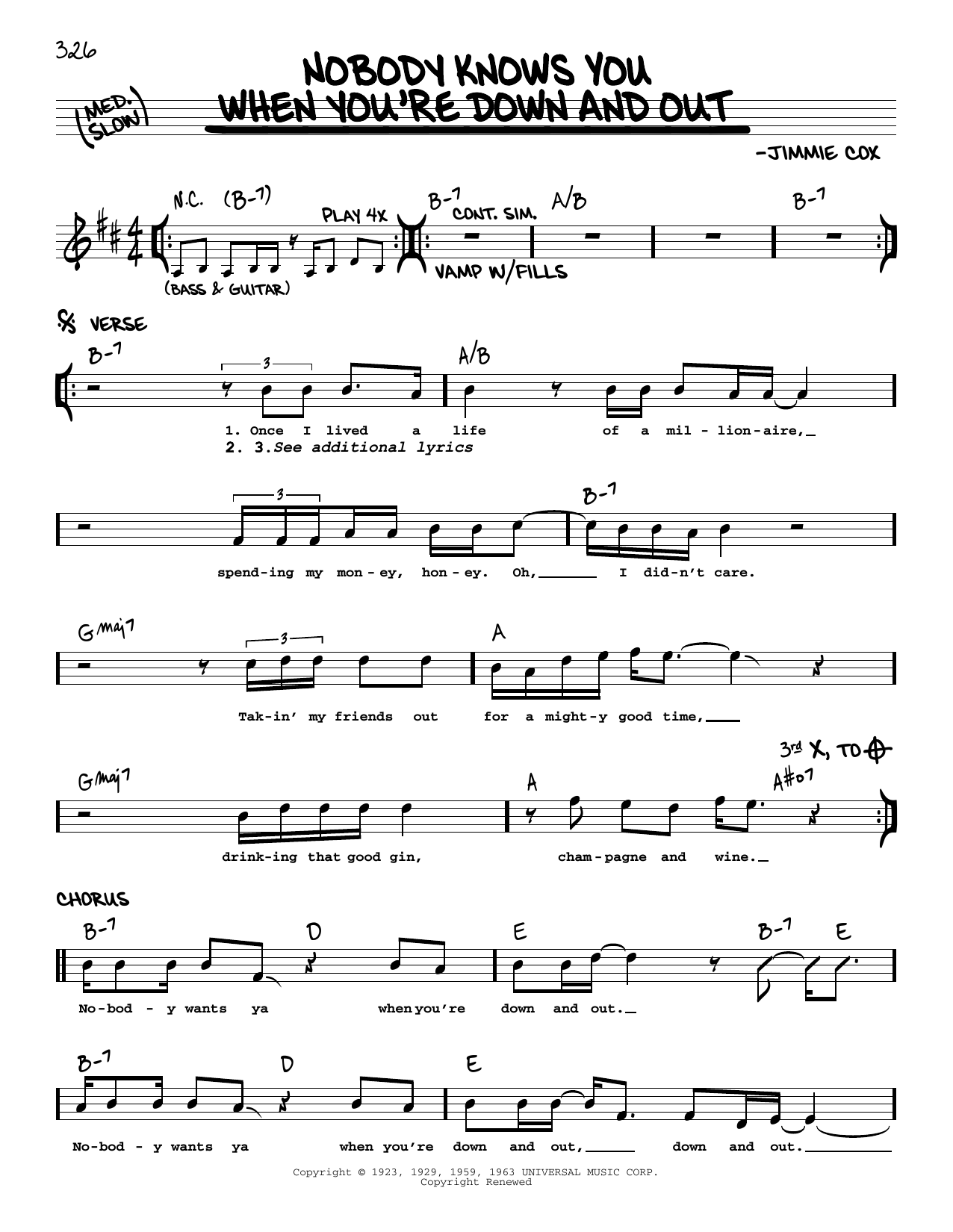

The song itself—"Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out"—is the definitive anthem of the fair-weather friend. Written by Jimmy Cox in 1923, it captured a specific kind of American anxiety. It wasn't just about being poor. It was about the social invisibility that follows financial collapse. One day you’re buying bootleg gin for a room full of laughing strangers, and the next, you’re standing on a street corner and those same people are looking right through you.

The 1929 Connection: Why the Timing Mattered

Cox wrote the song during the "Roaring Twenties," a time of excess and easy money. But it didn't truly explode into the cultural consciousness until Bessie Smith recorded it in 1929. The timing was eerie. She recorded it on May 15, just months before the stock market crash.

When the Great Depression hit, the lyrics weren't just a blues trope anymore. They were the news. Millions of people who had been "living high" suddenly found themselves in bread lines. Bessie Smith’s version—gritty, powerful, and deeply weary—became the soundtrack for a generation that learned, the hard way, that money is the glue in most social circles.

✨ Don't miss: Why Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory Tom and Jerry is Such a Bizarre Cult Classic

It's a brutal reality. People like winners. We gravitate toward success because we want some of it to rub off on us. When someone falls, they become a reminder of our own vulnerability. We stay away not just because they can't buy us drinks anymore, but because failure is perceived as "contagious."

Eric Clapton and the 70s Blues Revival

Fast forward to 1970. The world is different, but the feeling is the same. Eric Clapton, recording with Derek and the Dominos for the Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs album, brought the track back to life.

Clapton’s version stripped away the brassy vaudeville feel of the 1920s and replaced it with an acoustic, mournful exhaustion. It’s arguably one of his most authentic vocal performances. Why? Because Clapton was living it. Despite his fame, he was spiraling into heroin addiction and personal isolation. He knew exactly what it felt like to have the world at his feet one moment and feel completely abandoned the next.

Other Artists Who Felt the Burn

- Nina Simone: She gave it a sophisticated, jazz-inflected bitterness that felt like a political statement.

- Sam Cooke: His version was smoother, but the underlying sting of betrayal remained.

- Otis Redding: He brought a soul-wrenching grit that made the "down and out" part feel like a physical weight.

The Science of the "Fair-Weather Friend"

Why does this happen? Is everyone just inherently selfish? Evolutionarily speaking, humans are hardwired to seek high-status alliances. In our ancestral past, being around the person with the most resources (food, protection, influence) increased your own chances of survival.

When someone’s status drops, the "value" of the association drops. It sounds cold because it is. Psychologists often refer to this as "social exchange theory." Basically, we subconsciously tally up the costs and benefits of our relationships. If a friend is "down," they might need more emotional or financial support than they can give back. Many people, whether they realize it or not, simply bail when the "account" goes into the red.

Honestly, it’s a filter. A painful, miserable, soul-crushing filter. But it’s effective. You don't really know who your friends are when you’re winning. Success masks character. It’s only when the lights go out that you see who’s still sitting in the room with you.

Modern Invisibility: From Wall Street to Social Media

Today, nobody knows you when you're down has taken on a digital dimension. We live in a "highlight reel" culture. Instagram and TikTok are built on the aesthetic of winning.

If you're traveling, eating at Michelin-star restaurants, or celebrating a promotion, your engagement metrics skyrocket. People want to be seen with you. They comment "Goals!" and "Queen!" or "King!" under your photos.

But what happens when the content dries up? When you lose your job and can't afford the aesthetic anymore? Or when you're struggling with mental health and can't post a smiling selfie?

The silence is deafening.

In the 1920s, people stopped coming to your parties. In the 2020s, they just stop liking your photos and eventually unfollow. The "unfollow" is the modern version of crossing the street to avoid someone. It’s a low-effort way to distance yourself from someone else’s misfortune.

The Psychological Toll of Being "Out"

There is a specific kind of trauma associated with this social disappearance. It’s not just the loss of money or status; it’s the loss of identity. When people stop recognizing you, you start to wonder if you ever existed at all, or if you were just a prop in their lives.

- Identity Erosion: You begin to define yourself by your utility to others. If you aren't useful, you feel worthless.

- Paranoia: When things start to go well again, you find it impossible to trust new people. You’re always waiting for the moment they’ll leave.

- The "Lazarus" Effect: When you inevitably get back on your feet—and many do—the "friends" often come crawling back. They act like they were just "busy" or "didn't want to intrude."

Jimmy Cox’s lyrics cover this perfectly: “If I ever get my hands on a dollar again / I’m gonna hang on to it ‘til the eagle grins.” It’s a vow of self-reliance born out of betrayal.

How to Navigate the "Down" Periods

If you’re currently in the middle of a "nobody knows me" phase, there are ways to handle it that don't involve sinking into total bitterness.

Accept the Audit.

Think of this period as a brutal, involuntary audit of your social life. It’s clearing out the clutter. The people who stay—the ones who bring a pizza over when you’re broke or listen to you vent when you’re depressed—those are your "Tier 1" humans. Everyone else was just an extra in the movie.

Don't Fake the Up.

There’s a temptation to "fake it 'til you make it" just to keep people around. This is exhausting. It also prevents you from finding people who actually like the real, struggling version of you. Vulnerability is a great BS detector.

Build "Equity" in Real Relationships.

The song is a warning. If your relationships are built entirely on what you can do or buy for people, they will fail. True social security comes from emotional equity. It’s about being there for others when they are down, creating a reciprocal safety net.

Reclaiming the Narrative

The beauty of "Nobody Knows You When You're Down and Out" is that it’s usually told from the perspective of someone who survived. It’s a song of experience. To sing it, you have to have made it through to the other side.

The sting of being forgotten is real. It’s one of the most painful social experiences a human can go through. But there is a strange power in it, too. Once you’ve been "down" and realized you survived the silence, you stop being afraid of it. You stop performing for the crowd.

Actionable Steps for Rebuilding

- Audit your circle: Literally look at your call log. Who reached out when you had nothing to offer? Double down on those people.

- Invest in "Non-Market" Hobbies: Find things you love that have zero status attached to them. It keeps you grounded when the world’s opinion shifts.

- Practice Radical Self-Reliance: As the song suggests, "hanging on to your dollar" isn't just about money; it's about maintaining your own sense of worth independent of external validation.

- Acknowledge the Pain: Don't pretend it doesn't hurt when people leave. Acknowledge it, grieve the friendship, and move on. Keeping the anger inside just keeps you tied to the people who abandoned you.

The reality is that social tides ebb and flow. People are fickle. But the core of who you are doesn't change based on your bank account or your job title. The song has lasted a hundred years because that truth is universal. If you're down right now, just remember: the silence isn't a reflection of your value; it's a reflection of the limitations of the people around you.