Nina Simone didn't just sing songs; she performed exorcisms. When she sat at that piano, she wasn't looking to give you a "nice" evening. She wanted to wake you up. Honestly, if you listen to Nina Simone 4 Women—or just "Four Women," as the 1966 classic is actually titled—you can feel the room get colder. It’s heavy. It’s visceral.

The song is basically a six-minute masterclass in sociology. It tells the stories of four Black women, each representing a different archetype of the Black experience in America. But here’s the thing: when it first dropped on the album Wild Is the Wind, people lost their minds. Not in a good way. It was banned on several radio stations because critics thought it was "racist" or that it leaned too hard into stereotypes.

They completely missed the point.

The Raw Truth of the Four Archetypes

Simone wasn't celebrating these stereotypes; she was dragging them into the light to show how they were created by a system that never wanted these women to thrive. You’ve got to understand the historical weight here. She wrote this in a "rush of fury" after the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. That event, which killed four little girls, changed Nina. It turned her from a "supper club songstress" into a revolutionary.

Aunt Sarah

The first woman we meet is Aunt Sarah. Her skin is black, her back is strong, and she’s "taken the pain inflicted again and again." This isn't just a character; it’s the personification of the "Mammy" trope, the long-suffering woman whose only role was to serve. But Nina gives her a name. She gives her a voice that sounds like ancient earth.

Saffronia

Then comes Saffronia. Her skin is "yellow," and she lives "between two worlds." This is where Nina gets really uncomfortable for a 1960s audience. She explicitly mentions that Saffronia’s father was rich and white and "forced my mother late one night." It’s a direct indictment of the history of rape and colorism. Saffronia is the "tragic mulatto" archetype, caught in a limbo where she’s not white enough for privilege but often "too light" for total acceptance in her own community.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Sweet Thing

Next is Sweet Thing. She’s the prostitute. Her hips "invite you" and her "mouth is like wine." It would be easy to dismiss this as just another stereotype, but look closer. Nina asks the question: "Whose little girl am I?" It’s a heartbreaking reminder that this woman's body has been commodified because she had no other capital in a world that shut every other door.

Peaches

Finally, there’s Peaches. If the first three verses are a slow burn, Peaches is the explosion. Her manner is tough, she’s bitter, and she’s ready to kill. She represents the "Angry Black Woman," but Nina explains why she’s angry. "My parents were slaves," she shouts. The song ends with Nina literally screaming her name: "My name is PEA-CHES!" It’s a demand for recognition. It’s a refusal to be a nameless trope anymore.

Why the Song "Nina Simone 4 Women" Was Banned

It’s kinda wild to think about now, but radio stations in Philadelphia and New York pulled the track. Why? They claimed it insulted Black women. They thought by highlighting these archetypes—the servant, the light-skinned outcast, the prostitute, the embittered rebel—she was reinforcing them.

But Nina knew better. She once said that Black women didn't know what they wanted because they were defined by things they didn't control. By naming these women, she was handing them the keys to their own identities. She was saying, "I see you, and I know why you are the way you are."

In 2026, we look back and see it as a precursor to intersectional feminism. It wasn't just about race; it was about how race, gender, and class all pile on top of each other.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

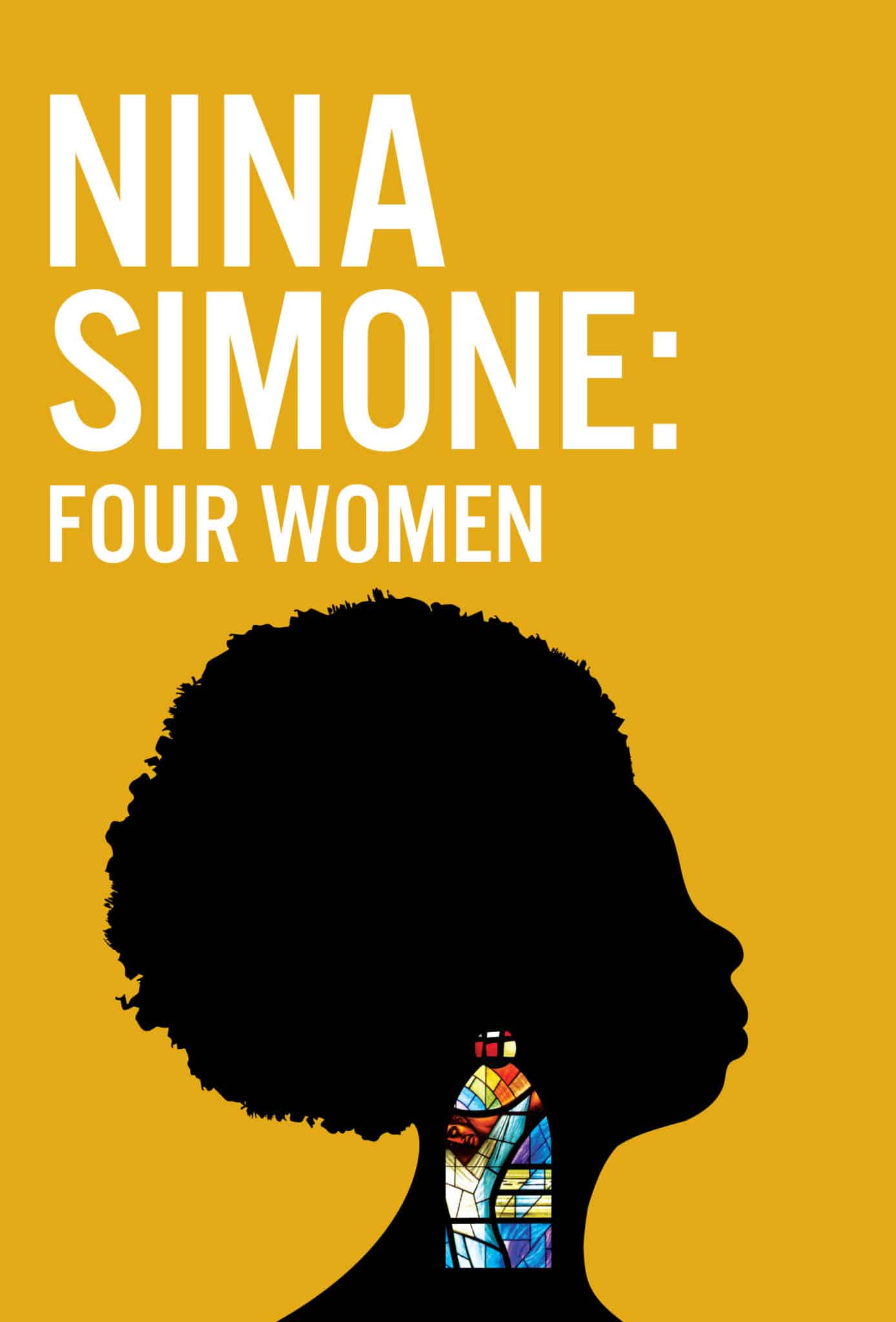

From Song to Stage: The Christina Ham Play

The song was so powerful it eventually inspired a play. In 2016, Christina Ham premiered Nina Simone: Four Women. It’s a brilliant piece of theater that imagines Nina meeting these three other women at the site of the Birmingham church bombing.

The play isn't a biopic. Don't go in expecting a "Greatest Hits" tour. It’s a psychological pressure cooker. It shows Nina—often played with "volcanic intensity"—struggling to turn her grief into the anthem that would become "Mississippi Goddam." The other women challenge her. They ask her why she’s singing for white folks in clubs while their world is burning.

It highlights the friction within the community. For example, the character of Sephronia (the Saffronia from the song) often represents the "Talented Tenth," the lighter-skinned elite who had a bit more protection. The play forces these women to argue, cry, and eventually harmonize. It’s that harmony that hits you like a tidal wave. When their voices merge, it’s a reminder that collective resistance is the only way out.

The Musical Genius You Might Miss

Musically, the song is fascinatingly simple but effective. It starts with that stately, repetitive piano figure. It feels like a funeral march. As each woman is introduced, the instrumentation shifts slightly.

- Aunt Sarah gets a steady, rhythmic pulse.

- Saffronia is joined by a "gently insistent" guitar.

- Sweet Thing has a bit more of a swing, almost like a jazz club vibe that hides the sadness.

- Peaches breaks the whole thing. The piano becomes dissonant. Nina’s voice cracks and turns into a growl.

By the time she reaches the final scream, the "perfect" structure of the song has completely disintegrated. It’s messy. It’s real. It’s exactly what protest music should be.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think Nina Simone was just "born" a civil rights icon. She wasn't. She wanted to be the first Black classical pianist. She studied at Juilliard. She applied to the Curtis Institute and was rejected—a rejection she felt was purely about the color of her skin.

That rejection is the ghost that haunts "Four Women." You can hear the classical training in the precision of the piano, but you can hear the pain of the rejection in the lyrics. She didn't want to be a protest singer; she had to be. She felt it was an artist's responsibility to reflect the times.

Actionable Insights: How to Engage with Nina's Legacy

If you really want to understand the depth of Nina Simone 4 Women, don't just stream it on a "Chill Jazz" playlist. That’s an insult to the work.

- Listen to the 1966 original and the 1970 live version back-to-back. You’ll notice how the live performance becomes much more militant and raw as the Civil Rights Movement shifted into Black Power.

- Read the lyrics as poetry first. Forget the music for a second. Look at the economy of the words. She says so much in just four lines for each character.

- Look into the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. To understand Peaches’ anger, you have to understand the smoke and the glass and the four little girls—Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Carol Denise McNair—who never got to be women.

- Watch the documentary 'What Happened, Miss Simone?' It gives context to her mental health struggles and how her activism cost her her career in the U.S.

The song is a mirror. If it makes you uncomfortable, good. It was meant to. It asks us to look at the roles we still force people into and the names we call them when they refuse to fit.

Ultimately, Nina Simone didn't just give us a song; she gave us a way to talk about things that are usually whispered. She took the "scab off the terrible sore" and made us look at it. That’s not just entertainment. That’s truth.