It was a simple lunch, or so the story goes. Barbara Ehrenreich, a journalist with a Ph.D. in cell biology and a knack for sharp-witted social critique, was sitting in an upscale French restaurant with Lewis Lapham, the editor of Harper’s. They were talking about welfare reform. This was the late nineties. The prevailing wisdom back then—pushed by politicians and pundits alike—was that anyone could make it if they just "got a job."

Ehrenreich wondered aloud how anyone actually survived on $6 or $7 an hour. Lapham’s response was basically a dare: "Why don’t you go out there and try it?"

She did. And the result, Nickel and Dimed, became a cornerstone of American literature. It wasn’t just a book; it was a wake-up call that still rings true in 2026. Honestly, if you haven’t read it lately, or at all, you’re missing the blueprint for understanding why the "help wanted" signs you see today don't tell the whole story.

The Experiment: Can You Actually Get By?

Ehrenreich set some ground rules for herself before she vanished into the world of the working poor. She wouldn't use her "real life" skills. She wouldn't fall back on her bank account unless things got truly dangerous. She’d take the best-paying job she could find and the cheapest housing available.

She started in Key West, Florida. Then she moved to Portland, Maine. Finally, she landed in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The goal? Simple. Match income to expenses.

But as she quickly found out, the math is a nightmare. In Key West, she worked as a waitress at "Hearthside" (a pseudonym for a Big Boy-style chain). She earned $2.43 an hour plus tips. That’s not a typo. $2.43. She had to take a second job as a hotel maid just to keep her head above water.

You’ve probably heard the phrase "nickel and dimed" used to describe small charges that add up. For Ehrenreich, it was literal. Every dollar was a battle. If she spent too much on gas, she couldn't afford a decent meal. If she stayed in a motel because she couldn't afford the first-and-last month’s rent for an apartment, the daily rate ate her whole paycheck.

It’s a cycle. A trap.

What Most People Get Wrong About "Unskilled" Labor

One of the biggest takeaways from Nickel and Dimed—and something people still argue about today—is the myth of "unskilled labor."

💡 You might also like: Trader Joe's Chinese Food: What Most People Get Wrong

Ehrenreich discovered that there is no such thing.

Cleaning a hotel room isn't just "cleaning." It’s a high-speed, physically grueling performance. You have to remember a dozen different chemicals, manage a heavy cart, and scrub floors on your hands and knees for hours. It requires stamina that would break a marathon runner.

At Walmart in Minnesota, she realized that even "just" folding clothes and directing customers is an exercise in mental endurance. You’re on your feet for eight hours. You’re being watched by managers who treat any moment of rest as "time theft."

It’s exhausting. It’s degrading.

And the pay? It’s a joke. She found that the wages she earned rarely covered the basic biological needs of a human being. We’re talking about food, shelter, and maybe—if you’re lucky—a bottle of aspirin for the back pain that never goes away.

The Hidden Costs of Being Poor

You might think being poor is just about having less money. It’s actually more expensive to be poor.

- Housing: If you can't save $2,000 for a security deposit, you end up paying $300 a week for a moldy motel room. That’s $1,200 a month. More than the apartment would have cost.

- Food: Without a kitchen or a refrigerator (common in cheap motels), you can't buy in bulk. You eat fast food or convenience store snacks. It’s expensive and it kills your health.

- Time: When you don't have a reliable car, you spend three hours on the bus. That’s three hours you can't spend working a second job or sleeping.

Ehrenreich pointed out that the "working poor" are actually the greatest philanthropists in our society. They work for less than it costs to live. In doing so, they subsidize the cheap services and goods the rest of us enjoy. They give their health, their time, and their children's future so we can have a $10 burger or a clean hotel room for $80 a night.

The Critics and the Controversy

Not everyone loved the book. Some critics argued that Ehrenreich’s experiment was flawed because she had a "safety net." She knew she could leave at any time. She wasn't really poor.

Others claimed she was too cynical. They pointed to people who "made it" on minimum wage as proof that she just didn't try hard enough.

But Ehrenreich was the first to admit she was "only visiting." She knew she brought her education, her health, and her "middle-class" confidence with her. If she couldn't make the math work with all those advantages, how is a single mother with a high school diploma and a chronic illness supposed to do it?

The book doesn't offer easy answers. It doesn't say "raise the minimum wage to $20 and everything will be fine." It highlights a systemic rot. It shows that the "American Dream" is often just a carrot on a very long, very broken stick.

Why We Are Still Talking About It

Since the book's release in 2001, the world has changed, but the struggle hasn't. Inflation has skyrocketed. Housing prices in cities like Austin, Seattle, or even smaller towns have made the "efficiency" apartments Ehrenreich stayed in look like a bargain.

In 2026, the "gig economy" has added another layer of precariousness. Instead of one bad boss at a restaurant, you have an algorithm at Uber or DoorDash that can "deactivate" your livelihood in a second.

Nickel and Dimed remains relevant because it forced us to look at the people we usually ignore. The woman cleaning your office at 2 AM. The guy stocking the shelves at the grocery store. The person who serves your coffee.

They aren't "unskilled." They aren't "lazy." They are often working harder than anyone else in the building for a fraction of the reward.

Real-World Takeaways for Today

If you want to apply Ehrenreich’s insights to your own life or community, here’s how to start:

- Check the Math: Look at the local "living wage" for your city. Compare it to the starting pay at nearby retail or service jobs. See if the gap has grown since you last checked.

- Support Housing Reform: The biggest hurdle Ehrenreich faced wasn't food; it was rent. Supporting "missing middle" housing or density in your neighborhood is a direct way to help the working poor.

- Humanize the Service: Next time you’re at a store or restaurant, remember that the person helping you is likely balancing a budget that doesn't quite add up. A little patience goes a long way.

- Read the Follow-up: If you liked this, check out Ehrenreich’s Bait and Switch. She tried the same experiment with white-collar jobs and found a different, but equally frustrating, set of traps.

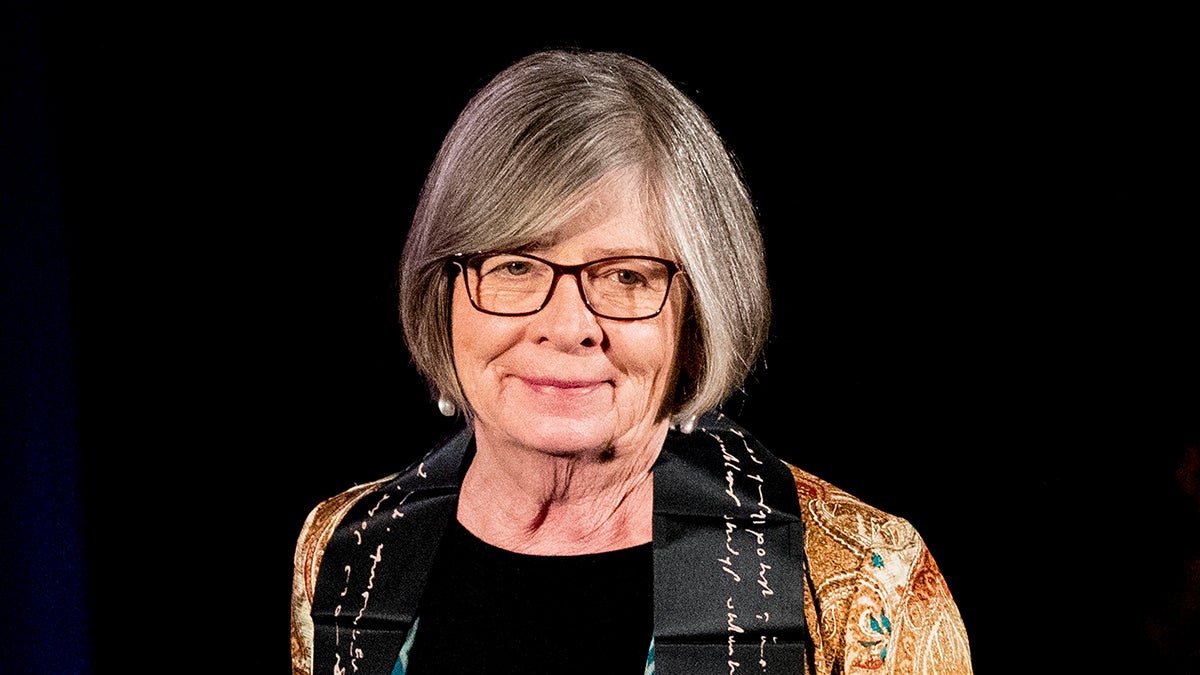

Barbara Ehrenreich passed away in 2022, but her work didn't. She didn't write to make us feel guilty. She wrote to make us see. She wanted us to realize that the "invisible" people around us are the ones holding the whole thing together. And right now, the floor they're standing on is getting thinner every day.

Practical Next Steps

To truly understand the modern landscape of labor, start by researching the "Living Wage Calculator" provided by MIT for your specific zip code. Compare that figure to the actual job postings in your area on sites like Indeed or LinkedIn. You’ll likely find that in most American cities, even a $15 or $18 hourly wage falls short of what’s needed for a single adult to cover basic housing, healthcare, and transportation without significant sacrifice. Understanding this gap is the first step toward advocating for policy changes that move beyond the surface-level rhetoric of "hard work equals success."