You’ve probably seen one and felt that immediate gut reaction. Maybe you laughed. Maybe you closed your laptop in a huff. That is the power of a New York Times cartoon, a medium that has somehow remained one of the most volatile pieces of real estate in American journalism. It’s weird, honestly. We live in an era of 4K video and instant viral clips, yet a few ink lines on a page can still cause an international diplomatic incident or a massive internal newsroom revolt.

People think these drawings are just filler. They aren't.

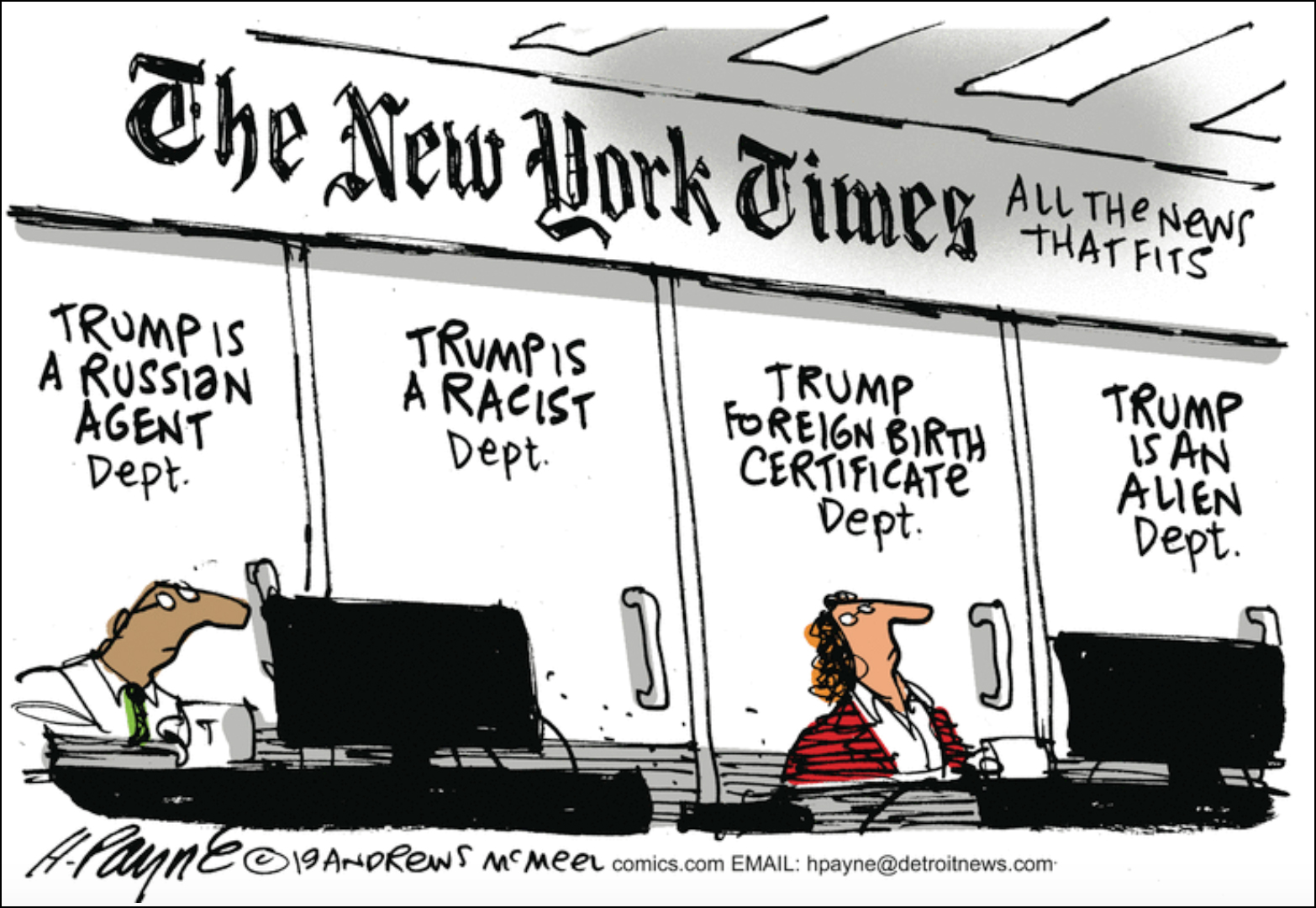

For decades, the "Grey Lady" has used visual satire to poke at the ribs of the powerful, but the path hasn't been smooth. It's been rocky. It's been messy. In 2019, the paper actually stopped running daily political cartoons in its international edition altogether after a massive outcry over a specific illustration. That decision sent shockwaves through the art world. Cartoonists like Patrick Chappatte, who had been a staple for years, suddenly found themselves without a platform. It raised a huge question: Can a legacy institution like the Times still handle the biting, often uncomfortable nature of caricature?

The 2019 Shift and Why It Changed Everything

To understand the New York Times cartoon landscape today, you have to go back to April 2019. An editorial cartoon featuring Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump was published in the international edition. It was widely condemned as anti-Semitic. The backlash was swift, global, and intense.

The Times apologized. They admitted the image was offensive. But then, they did something that caught everyone off guard. Instead of just tightening their oversight, they decided to axe in-house political cartoons from the international print edition entirely.

This wasn't just a policy tweak. It was a cultural earthquake.

Critics argued the paper was "cowardly." They said the Times was retreating from a vital form of expression because it was too scared of social media mobs. Editorial cartooning is supposed to be provocative. It’s supposed to live on the edge. When you remove the edge, what’s left?

Interestingly, the domestic edition of the New York Times has historically relied more on syndicated work or the famous "The Funny Pages" section in the Sunday Magazine, which leaned more toward long-form graphic journalism than the classic one-panel political jab. This distinction matters because it shows the paper's struggle to find a consistent voice in a visual medium.

Graphic Journalism: The New Frontier

While the traditional political "gag" cartoon took a hit, something else started to grow in its place. The New York Times cartoon evolved into what we now call graphic journalism. Think of it as a documentary, but drawn.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

It’s a different vibe. It’s more thoughtful.

Take the work of Sarah Akinterinwa or the late, great contributors who shifted from simple jokes to complex narratives. The "Op-Art" section frequently features illustrators who tackle massive topics—like climate change, mental health, or the housing crisis—using a sequence of panels rather than a single punchline. This isn't just "cartooning" in the 1950s sense. It’s high-level storytelling.

The paper found that while a single panel might get them in trouble, a three-page graphic essay allowed for nuance. Nuance is safer. It’s also, arguably, more impactful for a reader who is used to scrolling past memes all day. You have to slow down to read a graphic essay. You have to look at the details.

Why the Sunday Magazine is Different

If you want to see where the New York Times cartoon really lives now, you look at the Sunday Magazine. The "Talk" section often features quirky, stylized illustrations that accompany interviews. Then there’s the "New York Times for Kids" section, which is a masterclass in visual communication.

In the kids' section, the art isn't just a sidekick to the text. It is the text. They use comic strips to explain how the subway works or why the moon looks different every night. It’s brilliant because it respects the intelligence of the reader without being stuffy.

It’s kind of ironic. The main paper struggled so much with the "adult" political cartoons that it ended up finding its greatest visual success in sections meant for children and long-form intellectual deep dives.

The Viral Pressure Cooker

The internet changed the stakes for any New York Times cartoon. Back in the day, a cartoon lived for 24 hours on a piece of newsprint and then it was used to wrap fish. Now? A cartoon is clipped, shared on X (formerly Twitter), and analyzed by millions of people who don't even read the New York Times.

Context gets stripped away.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

That’s the danger zone. When a cartoonist draws for a specific audience—say, the highly educated, somewhat cynical NYT subscriber—they use a certain "visual shorthand." But when that shorthand hits the general public, it can be misinterpreted instantly. Caricature, by its very nature, exaggerates features. In a hypersensitive world, exaggeration often looks like bigotry or malice.

The editors are now in a position where they have to be "viral-proof." That’s a hard way to make art. It leads to cartoons that feel a bit "sandpapered"—all the rough edges have been smoothed down until the thing is safe, but maybe a little boring.

What People Get Wrong About the "Death" of NYT Cartoons

You'll hear people say the Times "killed" cartooning. That’s not quite right. They killed a specific type of cartooning.

If you look at the "Modern Love" column, you’ll see some of the most beautiful, evocative illustrations in modern media. Brian Rea’s work for that column, for example, is iconic. His thin-line drawings capture the loneliness and hope of New York City in a way a photo never could.

This is still cartooning. It’s just not "The Politician is a Pig" style of cartooning.

We are seeing a shift from satire to empathy. The modern New York Times cartoon is more likely to make you feel a quiet sense of recognition than a loud burst of anger. Whether that’s an improvement or a loss for democracy depends on who you ask. Most cartoonists would tell you it’s a loss. They believe the world needs people who can draw the uncomfortable truth in a way that words can't capture.

The Technical Artistry Behind the Scenes

Ever wonder how these pieces actually get made? It’s not just a guy with a pen anymore. Most of the illustrators working for the Times today are using a mix of traditional ink and high-end digital tools like Procreate or Adobe Fresco.

But the "Times style" is a real thing. It usually involves:

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

- A muted color palette (lots of greys, navy blues, and cream tones).

- Sophisticated use of negative space.

- A "hand-drawn" feel, even if it's digital.

- Concept-heavy imagery (e.g., a man walking a tightrope that is actually a DNA strand).

The goal is to look "smart." The New York Times cartoon doesn't want to look like a Sunday morning comic strip from the 90s. It wants to look like art that belongs in a gallery.

How to Follow New York Times Cartoons Today

Since the daily political cartoon is gone, you have to know where to look.

First, the Opinion section online is where most of the visual essays live. They often tuck these under the "Interactives" or "Opinion Video" tabs, which is a bit confusing, but the work is there.

Second, follow individual artists. The Times doesn't have a "staff cartoonist" in the traditional sense anymore, but they have a stable of regulars. Names like Liana Finck have brought a totally different, neurotic, and deeply relatable energy to the paper's visual identity. Finck’s work, which often appears in the New Yorker too, is the antithesis of the old-school political cartoon. It’s scribbly. It’s raw. It’s about the absurdity of being a human.

Third, check the "Daily" podcast art. Each episode of The Daily comes with a single square illustration. It’s a masterclass in editorial art—distilling a 30-minute complex news story into one compelling image.

Moving Forward: Why Visuals Still Matter

We are visual creatures. You can write a 4,000-word treatise on the collapse of the middle class, but a New York Times cartoon showing a family trying to stay afloat on a sinking dollar bill tells the story in three seconds.

The paper is still figuring out its relationship with the pen. It’s a nervous relationship. They want the prestige of great art, but they are terrified of the liability of a misunderstood joke.

If you’re a fan of the medium, the best thing you can do is support the artists directly. The era of the "all-powerful newspaper cartoonist" is mostly over. It’s been replaced by a gig economy of brilliant illustrators who hop from the Times to the New Yorker to their own Substack newsletters.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Visual Satire

- Look for the Subtext: When viewing a modern NYT illustration, ask yourself: "What is the metaphor?" It's rarely literal.

- Check the Credits: Most people ignore the tiny name in the corner. Start following those names on Instagram or Portfolio sites. That’s where the "uncensored" versions of their work often live.

- Compare the Versions: If you can find an International Edition and a Domestic Edition, look at the visual differences. The International version still tends to be slightly more "global" in its visual language.

- Support Graphic Memoirs: Many NYT cartoonists go on to write full-length graphic novels. If you like a particular style, check if they have a book. It’s the best way to see their vision without editorial "sandpapering."

The New York Times cartoon isn't dead. It’s just evolved into something more complex, more careful, and perhaps more artistic. It’s no longer just a punchline—it’s a conversation, even if that conversation is sometimes a bit tense.