If you could hop into a time machine and set the dial for New York in 1912, you’d probably want to pack a gas mask and some very sturdy boots. It wasn't the sepia-toned, romantic dreamland we see in old movies. It was loud. It was filthy. It was a city caught between the horse-drawn carriage and the subway, between extreme Victorian modesty and the roaring chaos of the industrial age. Honestly, 1912 was the year New York finally stopped pretending to be a small town and leaned into being a global monster.

The smell is what would hit you first. Over 100,000 horses were still working the streets. Think about that for a second. That is a staggering amount of manure being dropped daily on cobblestones, mixing with the soot from coal-burning furnaces and the salt spray from a harbor packed with steamships. It was the year of the Titanic disaster, the year a President got shot (and kept talking), and the year the skyline started looking like the Manhattan we recognize today.

The Ghost of the Titanic at Pier 54

You can’t talk about New York in 1912 without talking about the RMS Carpathia pulling into the Chelsea Piers on the night of April 18. It was raining. A cold, miserable drizzle. Thousands of people lined the West Side Highway, waiting for news that most of them already knew was going to be bad.

The Carpathia bypassed its own pier to drop off the Titanic’s empty lifeboats at Pier 59 first. A grim gesture. Then it swung back to Pier 54 to let off the 705 survivors. Imagine the scene: flashbulbs from newspaper cameras popping like tiny explosions, the sobbing of families, and the absolute silence of the wealthy elite from the Upper East Side standing shoulder-to-shoulder with immigrants from the Lower East Side.

This event fundamentally changed the city's mood. It broke the myth of "unsinkable" technology. For New Yorkers, the tragedy wasn't a distant news story; it was a local trauma. The names on the manifest—Astor, Straus, Guggenheim—were the names on the buildings they walked past every day. When Isidor Straus, the owner of Macy’s, went down with the ship, it felt like a pillar of the city’s economy had just evaporated.

A City Under Construction: The Rise of the Woolworth

While the harbor was mourning, the skyline was exploding. New York in 1912 was a massive construction site. If you looked toward Lower Manhattan, you would have seen the skeletal steel frame of the Woolworth Building rising toward the clouds.

Frank W. Woolworth, the king of the five-and-dime stores, was spending $13 million—all in cash, no loans—to build what would become the tallest building in the world. They called it the "Cathedral of Commerce." It was a transition point. The city was moving away from the squat, brownstone architecture of the 1800s and pushing into the Gothic skyscraper era.

💡 You might also like: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

Construction workers back then were basically acrobats. No harnesses. No hard hats. Just guys in flat caps walking across steel beams hundreds of feet in the air, eating sandwiches while dangling over Broadway. They were building a city that was growing faster than the infrastructure could handle. By 1912, the population was already over 5 million. People were squeezed into every available inch of space.

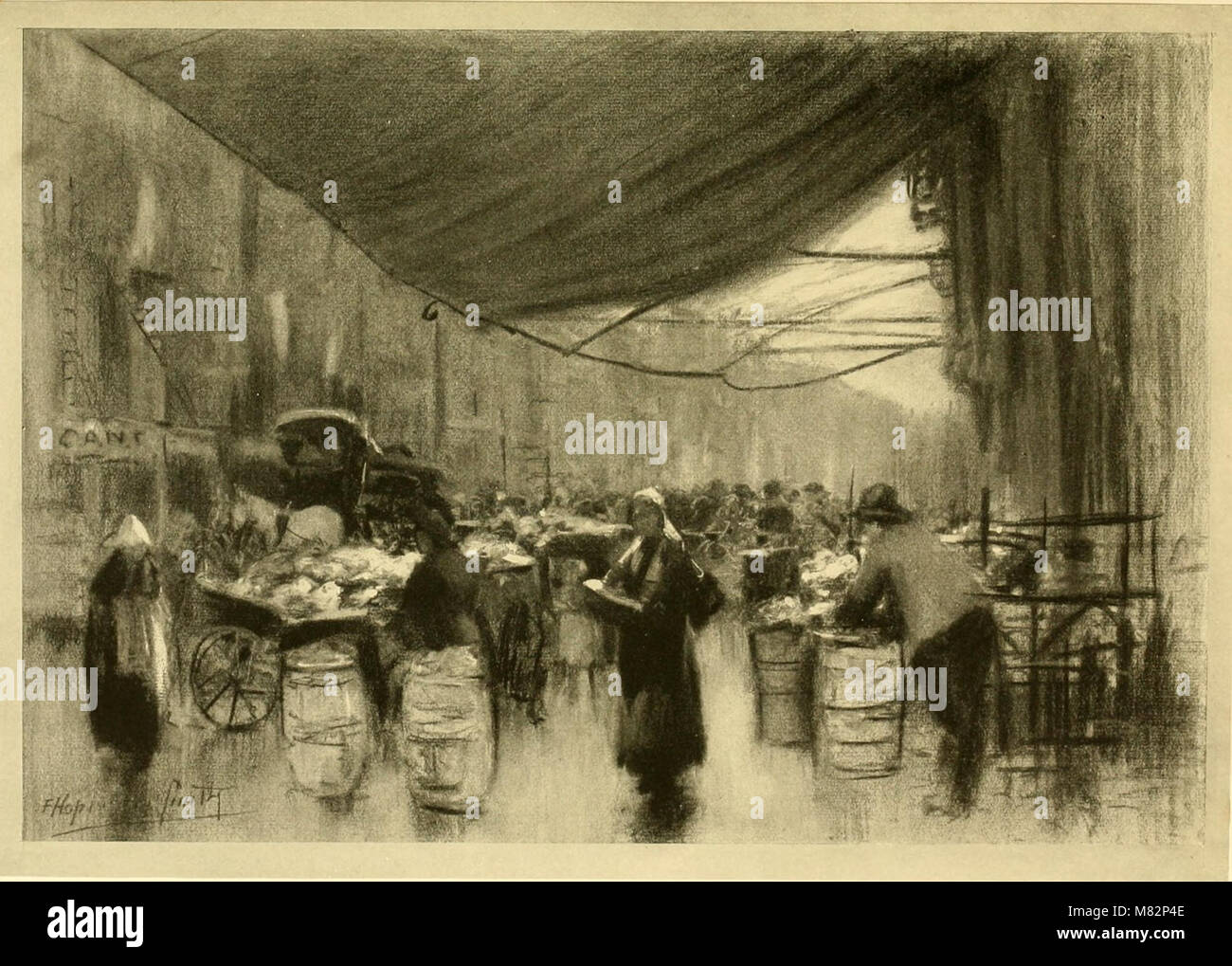

The Gritty Reality of the Lower East Side

Life was rough if you weren't an Astor or a Vanderbilt.

In the tenements of the Lower East Side, "density" wasn't just a word; it was a way of life. You’d have twelve people living in a three-room apartment. No indoor plumbing in many cases. The "air shafts" between buildings were usually filled with trash, and since 1912 saw several heatwaves, the stench was unbelievable.

Kids played in the streets because there were no parks. They’d play "stickball" or chase the ice wagons, trying to grab a chip of ice to suck on. It was a city of hustle. Everyone had a "side gig" before that was even a term. You’d see women doing "piecework"—sewing sleeves or buttons for the garment industry—by the light of a single kerosene lamp until 2:00 AM.

The shadow of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire still loomed large over New York in 1912. People were angry. They were starting to organize. This year saw a massive uptick in labor strikes. Waiters, garment workers, and even laundry workers were walking off the job, demanding things we take for granted now, like a 54-hour work week. Yeah, 54 hours was the "dream."

Corruption, Cops, and the Becker-Rosenthal Affair

If you think modern politics is messy, 1912 would make your head spin. This was the era of Tammany Hall, the political machine that basically ran New York like a private club.

📖 Related: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

The biggest scandal of the year—maybe the decade—was the murder of Herman Rosenthal. He was a bookmaker who was about to "squeal" to the District Attorney about police corruption. On July 16, 1912, he was gunned down outside the Hotel Metropole on 43rd Street.

The man who ordered the hit? Police Lieutenant Charles Becker.

It was the first time a New York City police officer was ever convicted of first-degree murder. The trial exposed the "System," a tangled web of cops, criminals, and politicians all taking their cut of the city’s gambling and prostitution money. It was a dark, gritty side of the city that showed New York wasn't just a place of progress; it was a place of deep-seated rot.

The Weird and the Wonderful

It wasn't all tragedy and corruption. New York in 1912 was also the birthplace of modern cool.

- The First Neon Sign: Well, technically, the first neon signs were popping up in Paris, but New York was starting to experiment with electric lighting that would eventually become the glowing heart of Times Square.

- The Subway Expansion: The "Dual Contracts" were being negotiated, which would eventually lead to the massive expansion of the subway system we use today.

- The Bull Moose Party: In August, Theodore Roosevelt—the ultimate New Yorker—was in the city for the Progressive Party convention. He’d been shot in the chest earlier that year and survived. His energy was the city's energy: loud, stubborn, and slightly dangerous.

- Vaudeville: If you wanted a night out, you went to the Palace Theatre or a nickelodeon. Silent films were starting to take off, but people still preferred the live chaos of acrobats, singers, and comedians.

The Great Transition

Basically, 1912 was the year New York grew up. It was the end of the "Gilded Age" and the start of the modern world. You had the opening of the new Main Library on 42nd Street (which had just happened in late 1911) providing free knowledge to the masses, while just blocks away, sweatshops were still grinding people down.

It was a city of massive inequality. You had the "Millionaire’s Row" on 5th Avenue with marble palaces, and then you had the "Hoovervilles" (though they weren't called that yet) of the homeless in the parks.

👉 See also: The Yogurt Shop Murders Location: What Actually Stands There Today

But there was an optimism there. You could feel that something big was happening. The city was vibrating with the sound of pneumatic drills and the shouting of newsies. "Extra! Extra! Read all about it!" wasn't just a movie trope; it was the soundtrack of the streets.

How to Explore 1912 New York Today

You can’t visit the 1912 version of the city, obviously, but the bones are still there if you know where to look. Most people walk right past history without realizing it.

- Visit the Tenement Museum: Located at 97 Orchard Street, this is the closest you will ever get to feeling the cramped, intense reality of 1912 immigrant life.

- Walk Pier 54: The rusted iron archway of the Cunard-White Star pier still stands on the West Side. It’s a haunting skeleton of the place where the Titanic survivors stepped onto dry land.

- The Woolworth Building: You can book small, private tours of the lobby. It is an explosion of mosaics and gargoyles (including one of Frank Woolworth himself counting nickels).

- Grand Central Construction: While the current terminal opened in 1913, in 1912 it was in its final stages of construction. Look at the surrounding buildings; many of them date exactly to this year.

The real takeaway from New York in 1912 is that the city has always been "collapsing" and "rising" at the same time. It’s never been a finished product. It was a mess then, and it’s a mess now—but that’s exactly why people keep coming.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs

If you want to dig deeper into this specific slice of time, don't just read a textbook. Look at the primary sources.

- Access the NYC Municipal Archives: They have digitized thousands of photos from 1912. Search for "Board of Estimate" photos—they took pictures of every building in the city for tax purposes. It’s like a low-resolution Google Street View from a century ago.

- Read "The Alienist" or "Ragtime": While fiction, these novels (especially Ragtime) capture the social friction and the physical atmosphere of the early 1910s better than most dry historical accounts.

- Check the Library of Congress Chronicling America: You can read the actual New York Times or New York Tribune from any day in 1912. Look at the ads. Seeing what a suit cost ($12) or what people ate for dinner (lots of oyster stew) makes the era feel human rather than historical.

New York in 1912 was a turning point. It was the moment the city decided to stop looking back at Europe and start looking up at the sky.