If you watch a lot of old movies, you've probably noticed they usually feel... polite. Even the "scary" ones from the early thirties often have this stagey, stiff quality that makes them feel like a museum piece. But then there is Mystery of the Wax Museum 1933. It’s different. It’s meaner. It’s weirder. It’s filmed in a color palette that looks like a bruised sunset, and honestly, it contains some of the most genuinely unsettling practical effects in the history of cinema.

Most people today know the story because of the 1953 remake House of Wax starring Vincent Price. That one is a classic, sure. But the original 1933 version? It was actually considered "lost" for decades. People thought it was gone forever until a print was found in Jack Warner’s personal vault in the late 1960s. Thank god they found it. Without this film, the "mad artist" trope in horror wouldn't be nearly as dark as it is.

The Two-Color Technicolor Nightmare

Let's talk about how it looks. This isn't your standard black-and-white flick. It was shot in Two-Color Technicolor. This was an early, expensive process that could only capture reds and greens. No blues. No yellows. Because of this limitation, everything on screen has this sickly, ethereal glow. The skin tones look slightly waxen even when the characters are alive. It’s accidental genius. It creates an atmosphere where you can’t tell where the human ends and the sculpture begins.

Michael Curtiz directed this. Yes, the same guy who did Casablanca. He was a notorious perfectionist—kinda a jerk on set, to be honest—but he knew how to move a camera. In an era where cameras were usually heavy and stationary, Curtiz had them gliding through the wax gallery, making the statues seem like they were watching you.

Mystery of the Wax Museum 1933: The Plot That Set the Standard

The story kicks off in London. Ivan Igor (played by the legendary Lionel Atwill) is a sculptor who loves his wax figures more than people. They’re his "children." When his greedy business partner burns down the museum for the insurance money, Igor is trapped in the fire. He’s presumed dead.

🔗 Read more: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

Fast forward twelve years to New York City. A new wax museum opens. Igor is back, but he's in a wheelchair, his hands supposedly burned and useless. He's "mentally" directing new assistants to recreate his lost masterpieces. At the same time, bodies are disappearing from the city morgue. You see where this is going.

What makes Mystery of the Wax Museum 1933 stand out is the character of Florence Dempsey. Played by Glenda Farrell, she is a fast-talking, cynical, wise-cracking reporter. She isn't a "damsel." She’s the one driving the plot. She’s the one who figures out that the statues look a little too much like the missing people. Her performance is so modern it almost feels like she stepped out of a 1970s newsroom and into 1933.

That Unmasking Scene (No Spoilers, But Wow)

If you haven't seen it, the climax features an unmasking that still holds up. Fay Wray—who became an icon the same year in King Kong—plays the lead girl, Charlotte. When she strikes the face of Ivan Igor and his "skin" literally shatters like a ceramic shell to reveal the burnt horror beneath... well, it’s a moment.

The makeup artist was Perc Westmore. He didn't have the fancy silicone or prosthetics they have now. He used layers of greasepaint, cotton, and spirit gum. It looked so gruesome that the censors at the time were losing their minds. This was just before the Hays Code (the strict Hollywood censorship rules) was fully enforced in 1934. Because of that, the movie gets away with stuff that would be banned just a year later. It’s got drug use, suggestions of necrophilia, and a level of cynicism that vanished from Hollywood for a long time afterward.

💡 You might also like: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Why the 1953 Remake Didn't Kill the Original

- Tone: The 1953 version is a gothic melodrama. The 1933 version is a gritty, urban crime thriller.

- The Heroine: Glenda Farrell’s reporter is way more interesting than the bland protagonists in the remake.

- The Color: Two-color Technicolor is simply creepier than the bright, vivid 3D color of the 50s.

- The Ending: It’s abrupt. It’s jarring. It doesn't give you a warm fuzzy feeling.

The Cultural Impact of the Wax Horror Genre

We take it for granted now. The "wax museum" is a horror staple. But Mystery of the Wax Museum 1933 was the blueprint. It tapped into a very specific fear called the Uncanny Valley. This is that psychological discomfort we feel when something looks almost human, but not quite.

The film deals with the obsession with physical perfection. Igor can't handle the "imperfections" of his burned body, so he tries to preserve beauty in a permanent, dead state. It’s a metaphor for the dark side of art. It asks: how much of yourself do you give to your work? In Igor’s case, everything. Literally.

Realism Over CGI

They used real people as statues. Curtiz forced the actors to stand perfectly still for long takes. If you look closely in some shots, you can see a "statue" blink or their chest move slightly from breathing. Strangely, this actually makes the movie scarier. It adds to the paranoid feeling that the statues are alive—or that the "live" people are already dead.

During the fire scene at the beginning, the wax figures were actually melting. The heat on set was so intense because of the massive lights required for the early Technicolor process that the actors were constantly on the verge of fainting. Fay Wray later recalled that the fear on her face wasn't always acting; she was genuinely terrified of the melting sets and the volatile chemicals being used.

📖 Related: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Finding and Watching It Today

For years, this movie was the "Holy Grail" for horror fans. When a restored version finally hit Blu-ray and streaming (thanks to the UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation), it was a revelation. The colors were stabilized. The hiss was taken out of the audio.

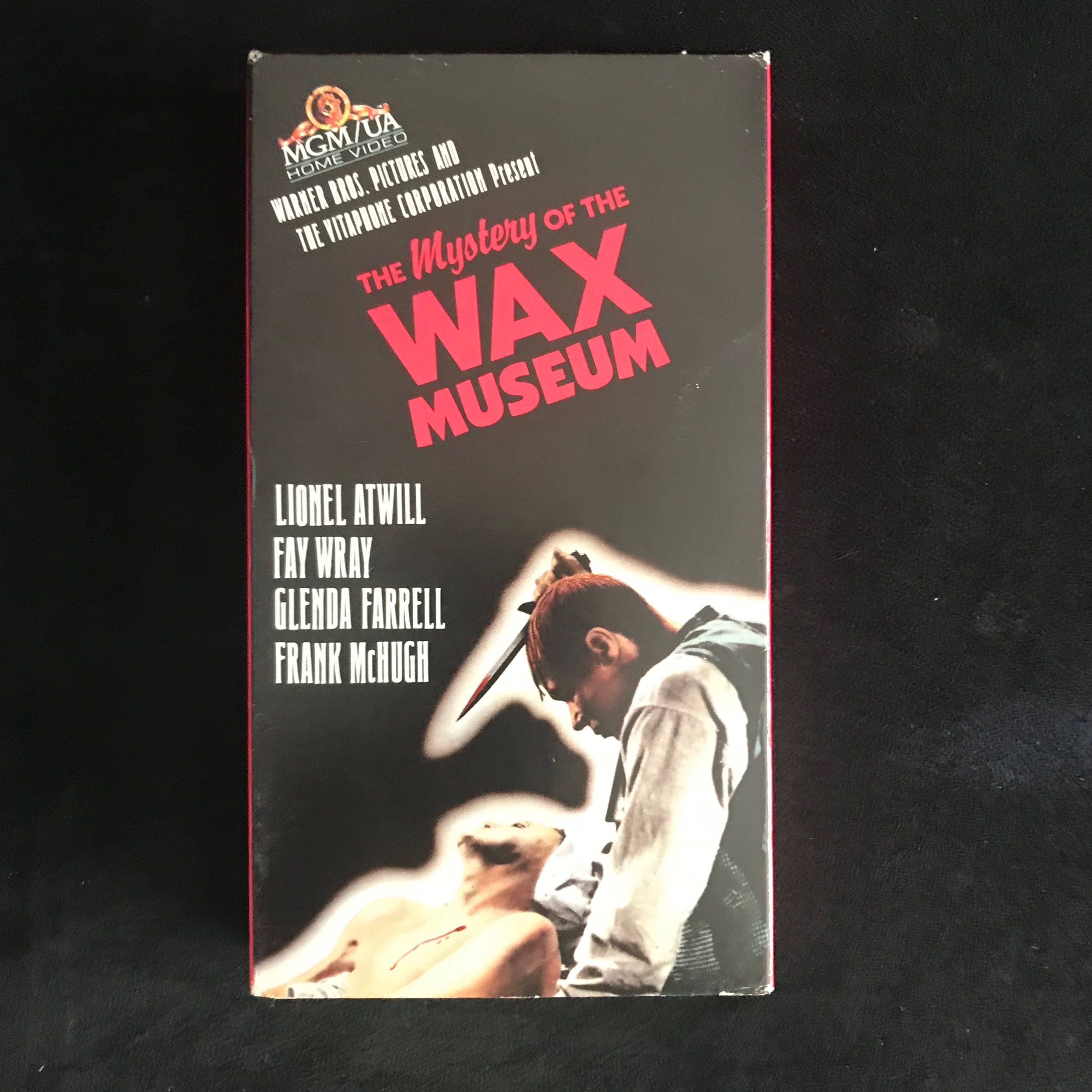

If you want to experience the real Mystery of the Wax Museum 1933, you have to watch the restored version. The old, bootleg VHS copies don't do justice to the green-and-red nightmare world Curtiz created. It’s a snapshot of a time when Hollywood was experimenting with how far they could push an audience's gag reflex.

Actionable Steps for Horror History Fans

If this movie sounds like your brand of weird, don't just stop at watching it. To really get the context of why this film was so radical, you should look into the "Pre-Code" era of cinema (1930–1934).

- Compare it to Doctor X (1932): This was Curtiz’s other "Two-Color Technicolor" horror film. It uses many of the same cast members and an even weirder "synthetic flesh" plot point.

- Look for the Restoration: Specifically, seek out the Warner Archive Blu-ray. It includes a featurette on the restoration process that shows exactly how they saved those decaying green and red frames.

- Analyze the Dialogue: Listen to Glenda Farrell's lines. She talks at a speed that modern actors struggle to match. It’s a masterclass in the "Fast-Talking Dame" archetype of the thirties.

- Visit a Wax Museum: Go to a Madame Tussauds. Stand in the corner. Look at the eyes of the figures. Then remember what Ivan Igor was hiding under that wax. It changes the vibe of the room pretty quickly.

The legacy of this film isn't just in the remakes. It's in every movie where a villain tries to "immortalize" beauty through violence. It’s a grim, beautiful, and slightly nauseating piece of history that proves horror didn't start with jump scares and CGI—it started with a flickering green light and a man who loved his art a little too much.

Next Steps for Discovery: Research the career of Lionel Atwill, who became the go-to villain for this kind of "mad doctor" role, and explore the filmography of Michael Curtiz beyond his famous dramas to see how he pioneered the visual language of the psychological thriller.