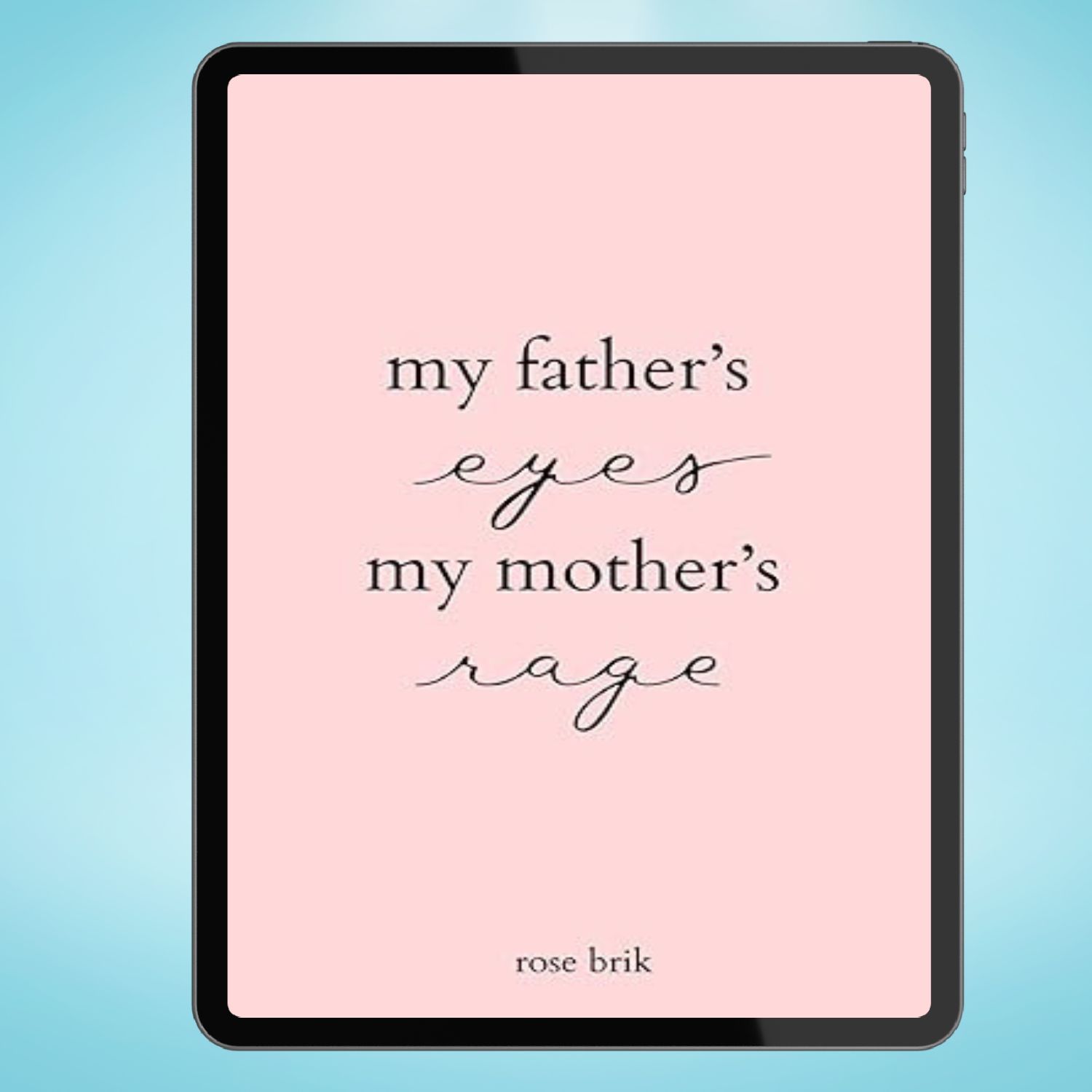

It starts with a line that feels like a gut punch. You’ve probably seen it scrolling through your feed, sandwiched between a recipe for sourdough and a video of someone’s cat. My father's eyes my mother's rage isn’t just a catchy phrase or a random string of words. It’s the opening of a poem that has basically become the unofficial anthem for anyone who grew up in a house where silence was loud and the air felt heavy before a storm.

People are obsessed with it.

Honestly, it’s rare for a piece of contemporary poetry to break through the digital noise like this. Usually, stuff that goes viral is short, punchy, and—let's be real—kind of shallow. But this is different. It hits on intergenerational trauma without using the clinical, boring language of a therapy textbook. It’s raw. It’s uncomfortable. It’s also frequently misattributed, misquoted, and misunderstood by the very people sharing it.

The Viral Origin of My Father's Eyes My Mother's Rage

So, where did this actually come from?

The poem is titled "Family Tree," and it was written by Warsan Shire. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because she’s the Somali-British poet who collaborated with Beyoncé on Lemonade. Shire has this incredible knack for taking the most painful parts of the human experience—refugee stories, domestic tension, body image—and turning them into something that feels both ancient and brand new.

When she wrote about having her father's eyes and her mother's rage, she wasn't just making a cool observation about genetics. She was talking about a "terrible inheritance." It’s that moment of looking in the mirror and realizing you’ve become a composite of the two people who maybe didn't know how to love each other, or you, quite right.

The poem doesn't celebrate the lineage. It interrogates it.

You see it on TikTok a lot now. People use the audio to talk about their own "almond moms" or their distant dads. But there’s a nuance in Shire’s work that gets lost in a fifteen-second clip. She’s talking about the weight of history. In the original context, the "rage" isn't just a bad mood. It’s a survival mechanism passed down through displaced families. It’s heavy.

Why the "Rage" Hits Different in 2026

We live in an era where everyone is hyper-aware of their "inner child."

💡 You might also like: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

Everyone is talking about breaking cycles. Because of that, my father's eyes my mother's rage has become a shorthand for the specific brand of baggage Gen Z and Millennials are trying to unpack. We’ve moved past the "my parents did their best" phase and into the "my parents' unaddressed trauma is currently sitting in my kitchen" phase.

It's about the physical manifestation of ghosts.

Think about it. You look in the mirror. You see your dad’s eye shape—maybe a bit downturned, maybe hazel. It’s a gift, right? But then you lose your temper at a red light or a dropped glass, and suddenly, your mother’s voice comes out of your throat. That’s the "rage." It’s the realization that you are a vessel for traits you never asked for.

The Science of Inherited Temperament

Is this all just poetic angst? Not really.

There’s actual science behind why this poem resonates so deeply. Behavioral genetics suggests that while we don't literally "inherit" a specific outburst, we do inherit a nervous system's baseline. Dr. Gabor Maté, a leading expert on addiction and trauma, often talks about how stressed parents pass down a physiological blueprint to their kids.

If your mother lived in a constant state of "rage" or high cortisol, your developing brain likely wired itself to be hyper-vigilant. You didn't just inherit her eyes; you inherited her fight-or-flight response.

- Epigenetics: This is the study of how your behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way your genes work.

- The Cortisol Link: Research from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine on Holocaust survivors showed that trauma can leave a chemical mark on a person’s genes, which is then passed down.

- Mirror Neurons: We learn how to react to the world by watching our primary caregivers. If rage was the primary language of your household, you’re likely fluent in it, even if you hate the dialect.

It’s a biological loop.

Shire’s poetry acts as a bridge between the clinical reality of trauma and the lived experience of it. When she writes about these inherited traits, she’s describing the epigenetic "ghosts" that scientists are only just starting to fully map out.

📖 Related: Bondage and Being Tied Up: A Realistic Look at Safety, Psychology, and Why People Do It

Misconceptions About the "Family Tree" Poem

One of the biggest mistakes people make when quoting my father's eyes my mother's rage is treating it like a "vibe."

It’s not an aesthetic.

I’ve seen Pinterest boards and Instagram carousels that pair these lines with soft-focus photography of wildflowers. That is... definitely a choice. It misses the point. The poem is actually quite dark. It mentions "a mouth full of blood" and "a body full of secrets." It’s about the violence of identity.

Another huge misconception? That the poem is an indictment of the parents.

If you read Shire’s full body of work, like Teaching My Mother How to Give Birth, you realize she has an immense amount of empathy for the "mother" in this equation. The rage isn't usually born from malice; it’s born from exhaustion, from being a woman in a world that doesn't hold space for your grief. By carrying that rage, the narrator isn't just suffering—they are remembering.

How to Handle the "Terrible Inheritance"

So, what do you do if you actually do have your father's eyes and your mother's rage?

You can't exactly swap out your DNA. And you can't go back in time and give your parents the therapy or the peace they probably needed.

Most people try to suppress it. They think if they’re "nice" enough or "calm" enough, the rage will just evaporate. Spoiler: It doesn't. It just turns into migraines or passive-aggression or a weirdly intense obsession with organizing your closet.

👉 See also: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

The real work is in the integration.

Acknowledge the Source

First off, name it. When you feel that heat rising in your chest—that specific, sharp anger that feels familiar—stop. Ask yourself: "Is this my anger, or is this the anger I learned?"

It sounds "woo-woo," but it’s actually a cognitive-behavioral technique. By labeling the emotion as a learned behavior rather than an inherent part of your soul, you create a tiny bit of distance. That distance is where your freedom lives.

Redefine the Traits

Your father's eyes are just eyes. They see the world.

Your mother's rage? At its core, rage is often just a boundary that’s been crossed too many times.

What if you took that "rage" and turned it into "fierce protection" or "uncompromising standards"? It’s the same energy, just directed differently. You can keep the intensity without keeping the toxicity.

Break the Loop

The poem ends—conceptually, at least—with the person standing there, holding all these pieces.

To break the cycle, you have to be willing to be the "boring" one in the family tree. The one who goes to therapy. The one who says, "I’m not going to scream back." The one who decides that the "eyes" will see something different than the generations before them.

Actionable Steps for Generational Healing

If you find yourself stuck in the cycle described in my father's eyes my mother's rage, there are concrete ways to start shifting the narrative. This isn't about "fixing" your parents; it's about reclaiming your own biology.

- Audit your triggers. Keep a note on your phone for one week. Every time you feel that "inherited" rage, write down what happened right before. Is it a lack of control? Is it feeling unheard? Usually, our parents' rage was triggered by very specific things. You might be surprised to find you’re reacting to their ghosts, not your reality.

- Practice "Somatic Experiencing." Since this kind of trauma is often stored in the body (the eyes, the jaw, the gut), talk therapy isn't always enough. Try movements that discharge nervous energy—shaking, dancing, or even just heavy lifting. Get the rage out of your muscles.

- Read the full poem. Don't just rely on the quote. Read Warsan Shire’s Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head. Context matters. Seeing the full arc of her struggle can help you map out your own.

- Set "Ancestral Boundaries." This doesn't mean you have to cut off your family (unless they are toxic). It means deciding that you will not participate in the family "language" of anger. If the conversation turns into that familiar heat, walk away. You don't owe the past your presence in its fire.

- Reclaim your reflection. Look in the mirror. Intentionally look at your eyes. Acknowledge who gave them to you, but then look at what you are doing with them today. You are the one behind them now. You’re in the driver’s seat.

The viral nature of these words proves one thing: you aren't alone in feeling like a walking museum of your parents' mistakes. But a museum is a place you visit; it’s not a place you have to live. You can carry the eyes and the history without letting the rage burn down everything you’ve worked to build.