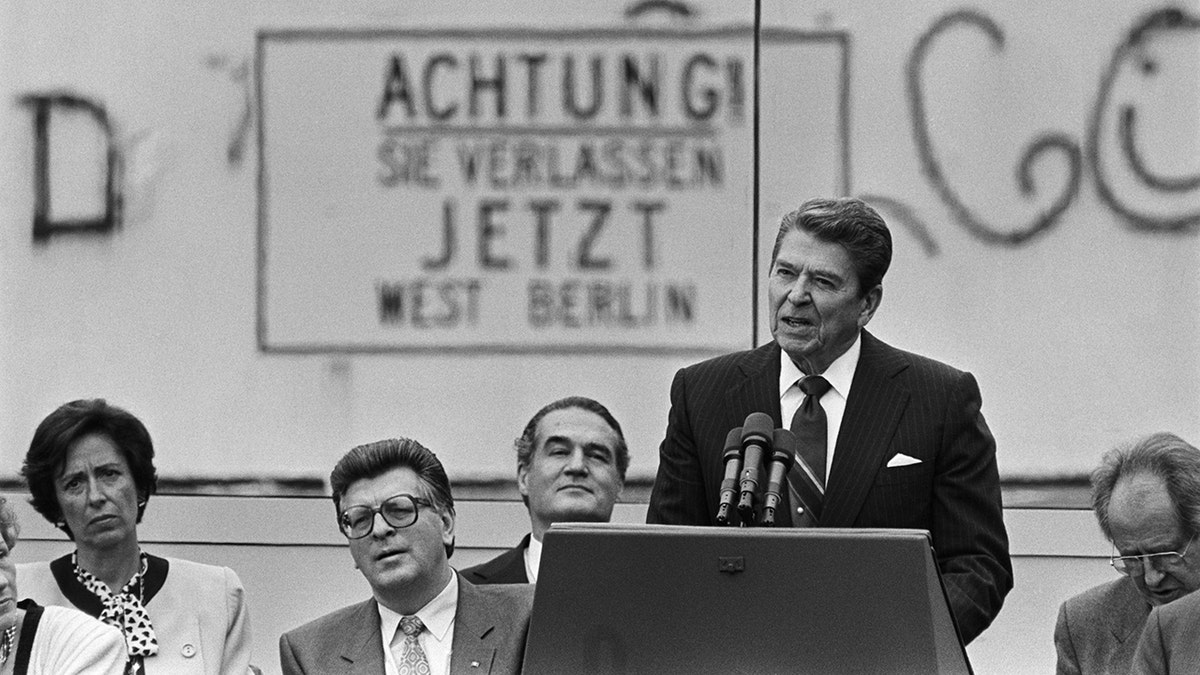

June 12, 1987. It was sweltering. Ronald Reagan stood behind two panes of bulletproof glass, staring at a massive concrete scar that divided a city and a world. He wasn't even supposed to say the line. His State Department advisors hated it. They thought it was too provocative, too aggressive, or just plain "un-presidential" for a time when relations with the Soviet Union were finally starting to thaw. But Reagan insisted. He leaned into the microphones, his voice echoing across the Brandenburg Gate, and uttered the words that would define the end of the Cold War: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!"

It’s one of those moments that feels inevitable in hindsight. We look at the grainy footage and think, "Of course he said that." But at the time? It was a massive gamble.

The Berlin Wall wasn't just some fence. It was a 96-mile psychological and physical barrier that had stood for twenty-six years. By 1987, most people had just accepted it as a permanent fixture of the European landscape. Reagan’s demand wasn't just a request for a construction crew; it was a direct challenge to the very legitimacy of the Soviet system.

The Battle Behind the Speech

Honestly, the internal drama at the White House was almost as intense as the standoff with the Soviets. Peter Robinson, the speechwriter who actually penned those famous words, has spoken extensively about how much pushback he got. The "experts" in the State Department and the National Security Council tried to cut that line at least seven times. Seven.

They thought it was "crude." They thought it would insult Mikhail Gorbachev, the reform-minded Soviet leader who was trying to implement glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring). The diplomats wanted something soft. Something subtle. They wanted Reagan to talk about "international cooperation" and "mutual understanding."

Reagan wasn't having it.

During the limousine ride to the Brandenburg Gate, Reagan told his deputy chief of staff, Ken Duberstein, that he felt he had to leave the line in. He knew the people of West Berlin needed to hear it. He knew the people of East Berlin, who were listening via smuggled radio signals, needed to hear it.

Why the Speech Didn't Work—At First

Here is the thing most history books gloss over: the speech was kind of a flop initially.

📖 Related: Latest Presidential Election Polls: What Most People Get Wrong About the 2028 Race

The Soviet news agency, TASS, called it "openly provocative" and "war-mongering." The American press didn't give it much play either. The New York Times buried the story. It wasn't until 1989, when the wall actually started coming down, that the "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall" line was resurrected as a prophetic masterpiece.

We love a good hero story. We love the idea that a single man shouted at a wall and it crumbled. But the reality is way more complicated. Gorbachev didn't just hear the speech and go, "You know what, Ron? You’re right. Let's get the sledgehammers."

The Soviet Union was broke. They couldn't afford to keep the Eastern Bloc under their thumb anymore. There were massive protests in Poland with the Solidarity movement. People in Hungary were already cutting holes in the barbed wire fences. East Germans were fleeing through Czechoslovakia. The wall didn't fall because of one speech; it fell because the entire Soviet structure was suffering from systemic rot and a massive surge of "people power."

The Man on the Other Side: Mikhail Gorbachev

You can't talk about Reagan's demand without talking about the guy he was actually talking to. Mikhail Gorbachev was a different kind of Soviet leader. He was younger, more energetic, and he realized that if the USSR didn't change, it would collapse.

When Reagan yelled "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall," he was essentially calling Gorbachev's bluff. He was saying, "If you're serious about reform, if you're serious about peace, prove it."

Gorbachev’s restraint is actually the unsung part of this story. In 1956 in Hungary and 1968 in Czechoslovakia, the Soviets sent in tanks to crush protesters. In 1989, when the wall finally came down, Gorbachev kept the tanks in the sheds. That’s a huge deal. Without Gorbachev’s willingness to let go, that speech might have just been a footnote in a much bloodier history.

The Brandenburg Gate as a Stage

The geography of the speech mattered. Reagan stood at the Brandenburg Gate, which was technically in the British sector of West Berlin, but the gate itself was just inside East Berlin. He was literally speaking across the border.

The wall there was actually two walls with a "death strip" in between—landmines, guard towers, and dogs. Reagan's back was to the wall. He was facing the West, but his voice was aimed East.

✨ Don't miss: Dwight D Eisenhower Born: The Truth About Ike's Texas Roots

There's a specific nuance people miss about the text of the speech. Reagan didn't just talk about the wall. He talked about the "Marshall Plan." He talked about the economic success of West Germany compared to the stagnation of the East. He was making an argument for capitalism and freedom as much as he was asking for a physical barrier to be removed.

What Most People Get Wrong About 1989

There's this misconception that Reagan said the words and then, boom, the wall fell.

It took two more years.

And when it happened, it happened because of a bureaucratic mistake. An East German official named Günter Schabowski accidentally announced during a press conference that travel restrictions were being lifted "immediately, without delay." He hadn't been fully briefed. He messed up the timing. Thousands of people rushed the checkpoints, and the guards—lacking clear orders and unwilling to shoot—just opened the gates.

Reagan’s speech provided the moral framework, but a bungled press conference provided the spark.

Modern Echoes and Lessons

Why do we still talk about this? Because it’s the ultimate example of "conviction politics."

📖 Related: Why 8647 is Everywhere: What 8647 Means on Protest Signs and Why It Matters

Reagan was told by everyone in his inner circle that the line was a mistake. He did it anyway. It reminds us that words, when backed by a clear moral stance, have a long tail. They might not change the world on Tuesday, but they might be the foundation for what happens two years later.

If you go to Berlin today, you can see the line where the wall stood. It's marked by double rows of cobblestones. It’s a tourist attraction now. You can buy "original" pieces of the wall in gift shops (though, honestly, most of them are just painted concrete from construction sites).

But the "tear down this wall" sentiment remains the benchmark for how leaders talk about freedom.

Actionable Takeaways from This Moment in History

To truly understand the impact and apply its lessons today, consider these perspectives:

- Look past the "official" narrative. When researching historical events, look for the internal memos. The fact that Reagan's advisors tried to kill the "tear down this wall" line tells you more about the political climate of 1987 than the speech itself.

- Acknowledge the role of the "other side." History isn't a monologue. Reagan's speech worked because he had a counterpart in Gorbachev who was—willingly or not—prepared to let the change happen.

- Understand the power of the "unfiltered" message. Reagan’s insistence on keeping the line despite professional advice is a masterclass in knowing your own brand and message. Sometimes the experts are too close to the problem to see the solution.

- Visit the Berlin Wall Memorial (Gedenkstätte Berliner Mauer). If you really want to feel the weight of Reagan's words, don't just go to the Brandenburg Gate. Go to the Bernauer Strasse memorial. It’s the only place where you can see the wall, the death strip, and the guard towers as they actually were. It’s haunting.

The speech wasn't just about Berlin. It was about the end of an era. When Reagan said "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall," he wasn't just talking to a Soviet leader; he was talking to history. And eventually, history listened.

To see the physical legacy of this moment, you can track the fragments of the wall that were sent to various presidential libraries across the United States. Each piece serves as a reminder that even the most "permanent" barriers are actually quite fragile when enough people decide they've had enough.