Elizabeth Prentiss wasn't trying to write a hit. She was actually just trying to survive a nightmare.

You’ve probably heard the hymn More Love to Thee in a dusty church or maybe a movie soundtrack. It sounds sweet. It sounds peaceful. But the backstory is anything but peaceful. It’s actually kind of metal when you realize it was written by a woman who had lost almost everything and was sitting in the wreckage of her life.

The Brutal Reality Behind the Lyrics

It was 1856. Elizabeth Prentiss was living in New York City, and things were going south fast. A massive plague of ship fever—what we now call typhus—was ripping through the city. In a terrifyingly short window of time, she lost two of her children.

Imagine that. Just total, crushing silence in a house that used to be loud.

Elizabeth was already a chronic invalid. She spent most of her life in physical pain, battling insomnia and what we’d now call clinical depression. After the kids died, she basically hit a wall. She told her husband, George, that she couldn't see how God could be good anymore. She was done.

But then, she grabbed a pen.

She didn't write a manifesto about how happy she was. She wrote a prayer that was basically a desperate ask for more capacity to love, even when life felt like a dumpster fire. That’s where More Love to Thee came from. It wasn't written for a choir; it was written for her own sanity. She actually tucked the poem away in a drawer and didn't show it to anyone—not even her husband—for thirteen years.

Why We Still Care About More Love to Thee in 2026

Honestly, the reason this song still pops up on Spotify playlists and in modern worship settings isn't just tradition. It’s the honesty.

👉 See also: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The lyrics talk about "earthly joy" being something the author used to seek. She admits she was chasing things that didn't last. There’s a specific line: “Once earthly joy I sought, sought peace and rest; now thee alone I seek, give what is best.” That’s a huge shift in perspective. It’s moving from "make my life easy" to "make my heart better."

Most of us are constantly seeking "peace and rest" in the form of a vacation, a better job, or just a quiet weekend. Prentiss is arguing that when those things get stripped away, you're left with a choice: get bitter or find a deeper kind of love.

Breaking Down the Hook

The melody we know today wasn't actually the original. Howard Doane composed the tune "More Love to Thee" in 1870. He’s the same guy who wrote the music for "Pass Me Not, O Gentle Savior." He had this knack for taking heavy, soulful lyrics and giving them a melody that felt like a deep breath.

It’s a simple tune. It doesn't have complex modulations or weird time signatures. It’s repetitive on purpose. The phrase "More love to Thee, more love to Thee" acts like a mantra.

The Psychological Impact of Lament

Modern psychologists often talk about the "lament." It's the idea that you have to acknowledge the pain before you can move past it. Elizabeth Prentiss was a master of the lament.

She wrote a famous book called Stepping Heavenward. If you haven't read it, it’s basically a fictionalized diary of a woman growing up and dealing with the mundane, annoying, and heartbreaking parts of life. It was a massive bestseller in the 19th century because it didn't pretend life was easy.

When you look at More Love to Thee through that lens, it’s not just a religious artifact. It’s a tool for emotional regulation. It’s about leaning into the pain.

✨ Don't miss: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

The Verse That Hits Different

The third verse is usually the one that makes people stop and think:

“Let sorrow do its work, send grief and pain; sweet are thy messengers, sweet their refrain.”

That is a wild thing to say. Who calls grief a "sweet messenger"?

Most people spend their entire lives running away from sorrow. We distract ourselves with phones, work, and noise. Prentiss is saying, "Let it do its work." She believed that suffering was a furnace that burned away the junk and left something purer behind. You don't have to be religious to appreciate the grit required to look at your own pain and say, "Okay, teach me something."

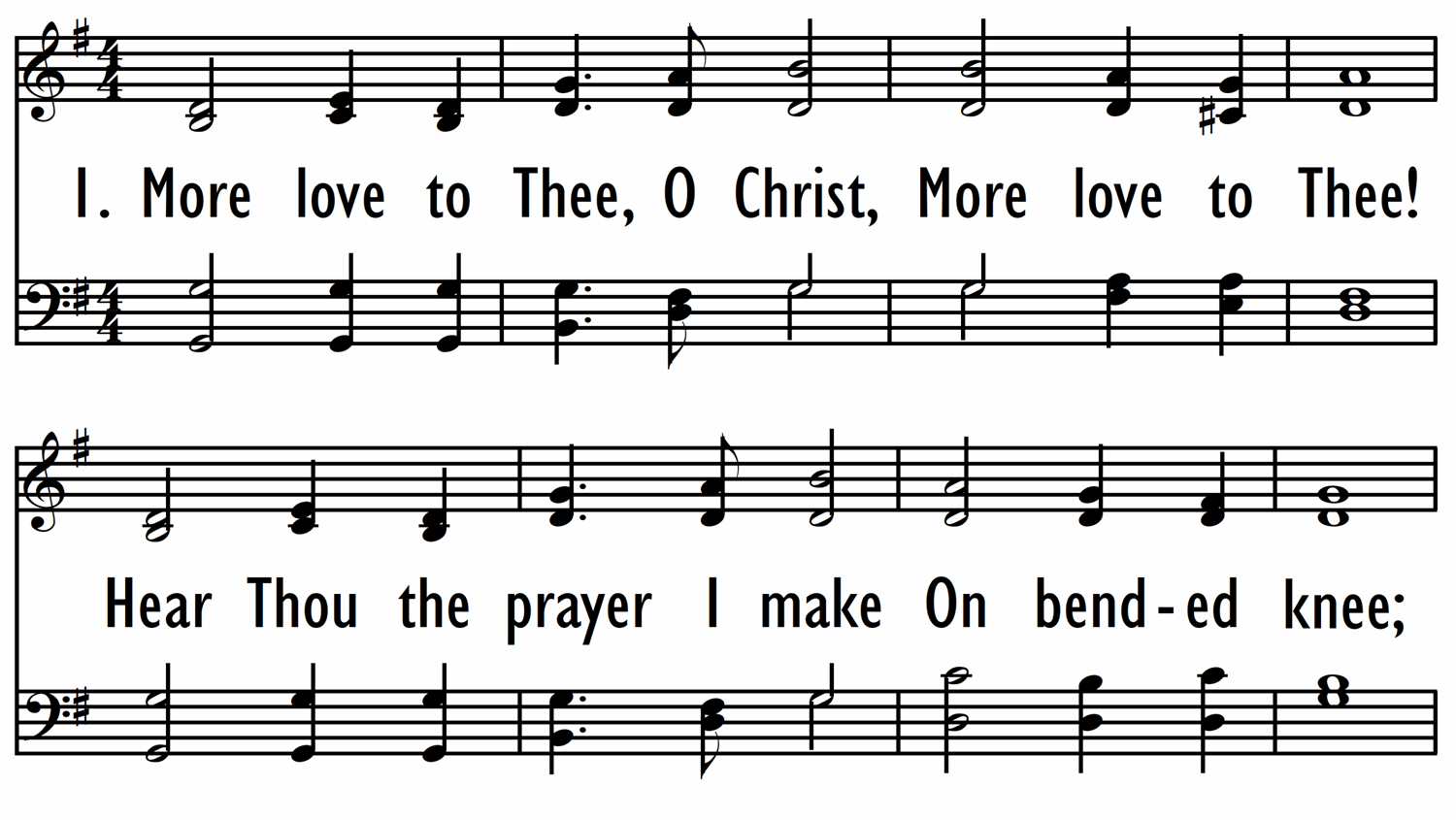

Technical Bits for the Musicians

If you’re trying to play this, it’s usually set in the key of G or A-flat. It’s a 4/4 time signature, but it often feels like it’s swaying.

- Structure: It follows a standard hymn structure—verse, then a refrain that repeats the title.

- Chords: It mostly sticks to the I, IV, and V chords (G, C, and D in the key of G).

- Vibe: If you’re arranging this for a modern setting, less is more. A simple acoustic guitar or a felt piano works way better than a full band because the lyrics are so intimate.

Misconceptions About the Song

People often think this is a song about being a "perfect" person. It’s actually the opposite. It’s a song for people who feel like they aren't loving enough.

It’s an admission of lack.

🔗 Read more: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Another misconception is that it was written by some stoic monk. Elizabeth was a mother who liked flowers and had a sharp wit. She was human. She struggled with her temper. She struggled with her health. When you realize a real, breathing, hurting person wrote these words, they carry way more weight.

How to Actually Apply This Today

You don't have to be a 19th-century poet to get something out of this. The core idea—choosing love over bitterness during a crisis—is a universal skill.

- Acknowledge the "Earthly Joys": Take a second to realize what things you're relying on for happiness. Is it your status? Your comfort? What happens if they disappear tomorrow?

- Practice the Lean-In: Next time something goes wrong, instead of immediately trying to fix it or escape it, ask what that "messenger" is trying to tell you. It sounds cheesy, but it’s literally what kept Prentiss from losing her mind.

- Simplify the Goal: Sometimes we try to solve 50 problems at once. The song suggests one goal: more love. If you focus on that, the other 49 problems usually feel a lot smaller.

Elizabeth Prentiss died in 1878. Her last words were reportedly part of the hymn she wrote in that dark room years earlier. She lived what she wrote. That’s why we’re still talking about it.

Practical Next Steps

If you want to dive deeper into this specific type of resilience, start by reading the letters of Elizabeth Prentiss. They aren't polished for publication; they're raw and often funny.

For musicians, try stripping the song down. Take the melody and play it as slowly as possible. Focus on the space between the notes. If you're using this for personal reflection, try writing your own "verse four." What are the specific "messengers" in your life right now? Naming them changes how much power they have over you.

Finally, check out different versions. From the classic Mormon Tabernacle Choir arrangements to the indie-folk covers by bands like Page CXVI, each version brings out a different shade of the emotion Elizabeth felt in 1856.