It is four in the morning. You are squinting at a screen, your eyes are burning, and you’re riding a digital horse through a digital desert. If you’ve played Rockstar Games’ masterpiece, you know exactly what I’m talking about. Missions in Red Dead Redemption aren't just checkboxes on a map. They’re basically a slow-burn western novel that you happen to be playing through.

Some games give you quests. Go here, kill ten rats, come back for a shiny hat. John Marston doesn’t do that. His life is a mess. He’s a guy caught between a dying era and a cold, industrial future. When you look at the design of these missions, they aren't always about being "fun" in the traditional sense. Sometimes they are lonely. Sometimes they are frustrating. But they always feel real. Honestly, that’s why we are still talking about them over a decade later.

The Weird Pacing of John Marston’s Life

Most open-world games try to keep you in a state of constant adrenaline. Red Dead Redemption (2010) didn’t care about that. It was bold enough to make you herd cattle.

Think about the mission "New Friends, Old Problems." You’re just... helping out on the MacFarlane ranch. It’s slow. It’s repetitive. You’re literally chasing cows. For some players, it was a slog. But for the story? It’s vital. It grounds John. It shows us what he wants: a quiet life. You can’t understand the tragedy of the ending without experiencing the boredom of the ranch first. Rockstar’s Dan Houser and the writing team knew that the "boring" parts of these missions were the emotional anchor.

💡 You might also like: Niky Wiki Genshin Impact: What Most People Get Wrong

Then, the game flips. Suddenly, you’re in "The Assault on Fort Mercer." This is the peak of the first act. It’s loud, violent, and chaotic. You’ve got a Gatling gun hidden in a wagon. It’s a classic western trope, but it works because the game earned it through those slower hours in New Austin.

Crossing the Border

If you ask any fan about the most memorable moment in the game, they won’t say a shootout. They’ll talk about "Far Away." You just crossed the river into Mexico. The music—Jose Gonzalez’s "Far Away"—kicks in. You’re just riding. No enemies. No objectives. Just the landscape.

Technically, this is part of a mission. But it’s a moment of pure atmosphere. It’s one of the few times a game has successfully used "dead air" to tell a story. It captures that feeling of being an outsider in a strange land. Mexico in the game feels different from New Austin. The missions there, like "The Gates of El Presidio," have a different weight. You’re caught between a revolution and a corrupt government. It’s messy. John doesn’t even want to be there, and you feel that exhaustion in the gameplay.

The Strange Folks You Meet

The "Strangers and Freaks" missions are where the game gets truly weird. These are side missions, sure, but they are just as important as the main path.

Take "I Know You." You meet a man in a top hat who seems to know everything about John’s past. He’s mysterious. He’s creepy. Is he God? Is he the Devil? Is he just a hallucination? The game never tells you. This mission breaks the "realism" of the world in a way that feels haunting. It forces the player to reckon with John’s morality. You realize that missions in Red Dead Redemption aren't just about the shooting; they are about the soul of the character.

- You help a man build a flying machine that inevitably fails.

- You track down a "cannibal" who turns out to be a pathetic, starving man.

- You find a man obsessed with a pile of rocks he thinks is a woman.

These missions provide a dark, comedic undercurrent to the main tragedy. They show a world filled with broken people who can't adapt to the changing times, just like John.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Pro Controller L Button Is Soft and How to Actually Fix the Mush

The Illusion of Choice and the Reality of Debt

One thing people get wrong about these missions is thinking they have a choice. You don't. John Marston is a man on a leash. The Pinkertons—Edgar Ross and Archer Fordham—are pulling the strings.

This is reflected in the mission design. Almost every mission starts with John being told what to do. He’s a servant to the law, a servant to revolutionaries, a servant to his own past. When you play "And the Truth Will Set You Free," and you finally corner Dutch van der Linde, it’s not a moment of triumph. It’s a moment of defeat. Dutch’s final speech about "gravity" isn't just dialogue; it’s the mission statement of the whole game. You can’t fight change. You can’t fight the law. You can't fight who you are.

The Contrast with RDR2

It’s impossible to talk about the first game’s missions without mentioning the sequel (or prequel). In Red Dead Redemption 2, the missions are much more scripted. They feel like a movie. They are beautiful, but they can feel restrictive. If you step two inches off the path, you get a "Mission Failed" screen.

The missions in the original Red Dead Redemption feel a bit more "wild." There’s a certain rawness to them. The gunplay is snappier, less weighted. The world feels emptier, which makes the missions feel more urgent. When you’re out in the Great Plains hunting bison for a stranger, the isolation is palpable.

The Ending That No One Expected

We have to talk about "The Last Enemy That Shall Be Destroyed."

This is arguably one of the most famous missions in gaming history. For a while, the game lets you think you’ve won. You’re back at the ranch. You’re doing chores. You’re teaching your son, Jack, how to hunt. It feels like the game is over, and you’re just playing an epilogue.

Then the army shows up.

The mission design here is brutal. You’re defending your home, but it’s a losing battle. You’re outnumbered. You’re outgunned. And then comes the barn. The use of "Dead Eye" in those final seconds is a genius bit of narrative gameplay. You think, just for a second, that maybe you can kill them all. Maybe you can win. But the meter runs out. The bullets hit.

The mission doesn't end with a "Game Over." It ends with a burial.

And then, the game does something even bolder. It gives you one more mission: "Remember My Family." It’s years later. You’re playing as Jack. You track down Edgar Ross. It’s a simple duel. It’s short. It’s quiet. And it’s the most unsatisfying, perfect ending possible. You’ve finished the cycle. You’ve become exactly what John didn’t want you to be.

Why We Keep Coming Back

Red Dead Redemption is a game about the end of things. The end of the frontier. The end of the outlaw. The end of a family.

The missions aren't just fun distractions; they are the bricks that build that house of cards. Even the "bad" missions—the ones where you're just riding for ten minutes listening to a crooked politician talk—serve a purpose. They build the world. They make the violence feel like it has consequences.

If you’re revisiting these missions today, especially with the newer ports on modern consoles, you’ll notice that they hold up surprisingly well. The lack of "hand-holding" compared to modern titles is refreshing. You’re often just given a gun and a general direction and told to figure it out. It feels like the Wild West should: dangerous and unpredictable.

Practical Ways to Experience the Best Missions

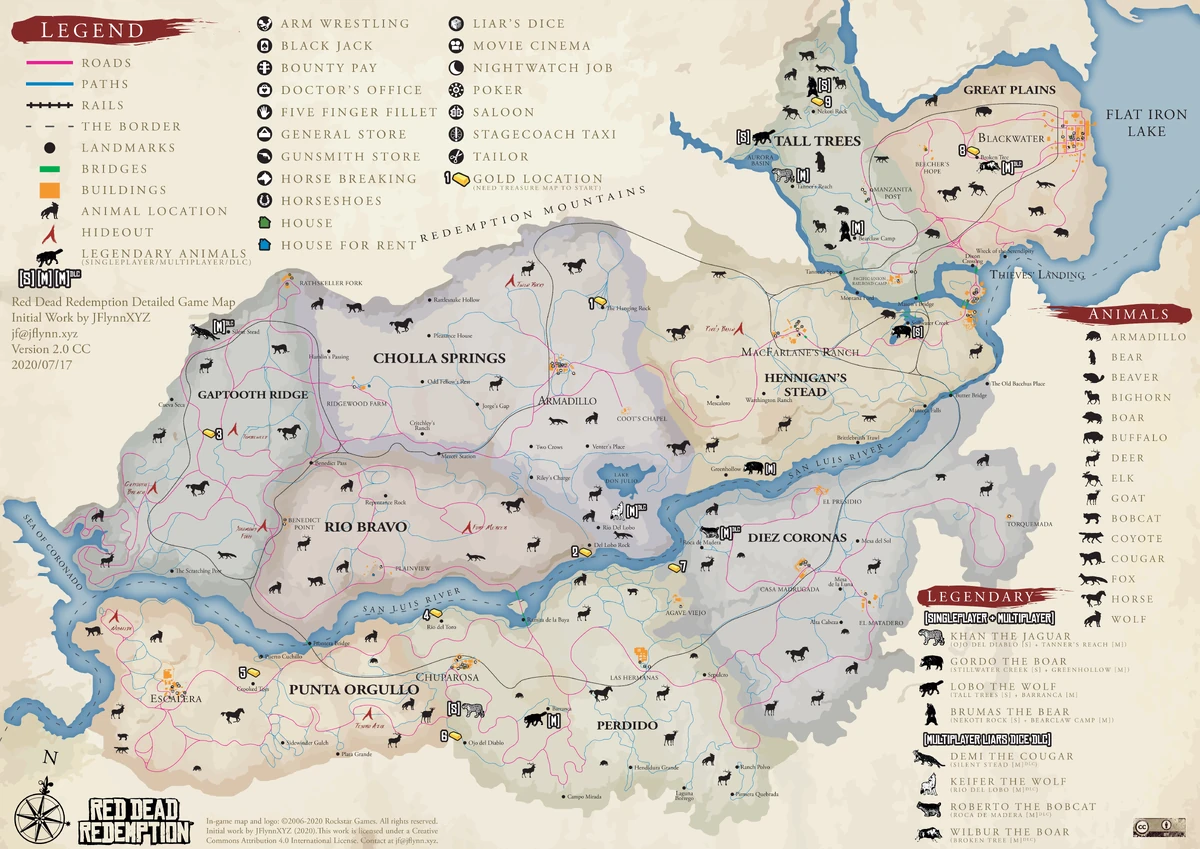

If you're jumping back in or playing for the first time, don't rush the "yellow" icons on the map. The gold is in the margins.

- Prioritize the Stranger Missions early. Some of them, like "I Know You," actually change or disappear depending on where you are in the main story. They provide context for John’s headspace that the main missions sometimes skip.

- Listen to the dialogue. Rockstar is famous for "travel dialogue." If you gallop ahead, you miss the character building. Keep your horse at a trot and let the voice actors do their work. Rob Wiethoff (John) puts so much gravel and regret into every line.

- Pay attention to the Honor System. How you complete certain missions—whether you kill a fleeing witness or let them go—affects how the world sees you. It changes the ambient dialogue in towns and even the horse you can buy. It makes the missions feel like your own personal story.

Moving Forward in the West

The legacy of missions in Red Dead Redemption is found in how they refuse to be "just a game." They demand your patience. They demand that you care about a man who has done terrible things.

When you finish that final duel as Jack Marston, and the title card splashes across the screen, it’s a heavy moment. You aren't just finished with a game; you’ve lived through an era. That’s the power of good mission design. It’s not about the mechanics; it’s about the memory.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Obsessed With New York Times Tiles Lately

To get the most out of your next playthrough, try a "No Fast Travel" run. It sounds tedious, but it forces you to engage with the world the way the developers intended. You'll stumble upon random encounters that feel like mini-missions, from stagecoach robberies to distressed damsels who are actually setting an ambush. It turns the entire map into one giant, seamless mission. This is where the game truly lives—in the unpredictable moments between the markers.

Stop looking at the mini-map and start looking at the horizon. The West is dying, and you’ve got a front-row seat. Enjoy the ride while it lasts.

Next Steps for the Ultimate Experience:

- Complete all 15 Stranger Missions before finishing the main story to see the full arc of John's moral journey.

- Track your progress in the "Social Club" or the in-game menu to ensure you don't miss the unique encounters in Mexico, which are easily skipped.

- Engage with the "Hunting and Trading" missions to unlock the Legend of the West outfit, which significantly boosts your Dead Eye abilities for the harder late-game shootouts.