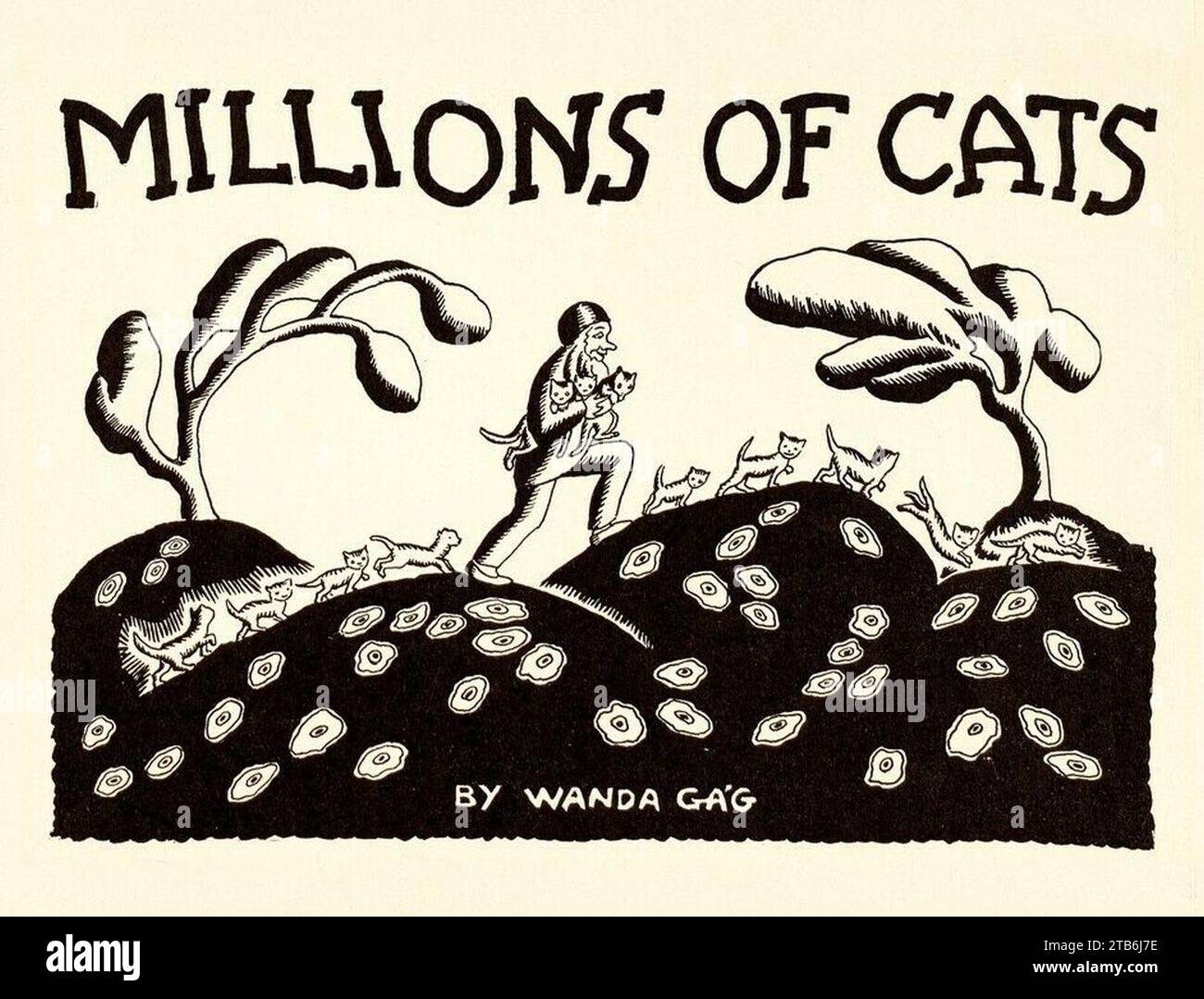

You’ve seen it. That distinctive, hand-lettered cover with the swirling hills and the sheer, overwhelming volume of felines. Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág isn't just an old book your grandmother kept in a dusty corner of the guest room. It’s a foundational pillar of American literature. Honestly, it's the reason the modern picture book even exists in the form we recognize today. Before 1928, children’s books were mostly stuffy, vertical affairs where the text stayed on one side and the pictures stayed on the other, like they were afraid of catching each other's germs.

Gág changed that. She broke the rules.

She grew up in New Ulm, Minnesota, the eldest of seven children in a household where art was basically the family religion. When her father died, his dying words were literally telling her to finish what he started. No pressure, right? She struggled through poverty, supported her six siblings, and eventually moved to New York, where she became a celebrated printmaker before ever touching a "children's story." That’s why Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág feels different. It isn’t "drawn" for kids in a condescending way; it is etched with the soul of a fine artist who understood that children can handle a little bit of darkness and a whole lot of visual complexity.

The Double-Page Spread That Changed Everything

Most people don't realize that before this book, the "double-page spread" wasn't really a thing. Gág was a pioneer. She used the gutter of the book—that middle crease—as a bridge rather than a wall. When the very old man walks through the rolling hills, the landscape flows across both pages. It creates a sense of cinematic movement. You’re not just looking at a stagnant image; you’re traveling with him.

It’s genius.

The rhythm of the text is just as intentional. "Cats here, cats there, cats and kittens everywhere, hundreds of cats, thousands of cats, millions and billions and trillions of cats." It’s a refrain. It’s a chant. It’s the kind of oral storytelling that feels like it’s been around for a thousand years, even though Gág actually wrote it herself based on the vibes of old European folktales she heard growing up in a German-speaking community.

Wait, Did the Cats Just Eat Each Other?

Let’s talk about the ending. It’s metal.

💡 You might also like: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

If you haven't read it recently, here’s the refresher: The very old man and the very old woman want one cat. He finds a hill covered in them. He can’t choose. He takes them all. When they get home, the cats get jealous. They start arguing about who is the prettiest. They have a massive, screeching blowout. Then... silence. The old couple peeks out, and all the cats are gone.

"I think they must have eaten each other up," the old man says.

Yeah. He actually says that.

Modern editors would probably lose their minds over that line today. They’d want a "teachable moment" or a "gentle resolution." But Gág knew better. Kids love a bit of the macabre. The only survivor is the "homely" little kitten who didn't join the vanity contest. It’s a survival-of-the-humblest story. It’s gritty. It’s weirdly honest about ego and greed.

Why Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág Still Ranks as a Must-Read

You might wonder why a black-and-white book from 1928 still sells copies in an era of iPad apps and neon-colored 3D animation. It's the E-E-A-T factor—Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness—not just for the author, but for the story itself. It has stood the test of nearly a century.

- The Lithographic Style: Gág used a specific type of greasy crayon on zinc plates. This gives the lines a thick, fuzzy, organic feel. It looks like it was grown out of the earth.

- The Newbery Honor: It won a Newbery Honor in 1929, which was incredibly rare for a picture book. Usually, those awards went to long novels for older kids.

- Hand-Lettering: Every word in the original was hand-lettered by Wanda’s brother, Howard Gág. This makes the text part of the art. The words follow the curves of the hills.

There’s also the historical context. Gág was a radical. She was a feminist who lived in a "free love" commune-style arrangement at her home, "Alligator Hill." She brought that rebellious spirit to her work. She didn't follow the Victorian standards of what a "nice" book should look like. She made something that felt alive and a little bit dangerous.

📖 Related: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

Common Misconceptions About the Story

Some people think it’s a folk tale from the "Old Country." It’s not. It’s a New Ulm, Minnesota original. Gág was so steeped in the folklore of her ancestors that she could synthesize the style perfectly, but the "Millions and Billions" refrain is her own invention.

Another mistake? Thinking the book is "too scary" for toddlers. Honestly, kids usually find the "eating each other up" part fascinating rather than traumatizing. It’s the adults who get squeamish. Children understand the logic of the story: if you are too full of yourself and you pick a fight with a million people, you’re probably going to have a bad time.

The Legacy of the Very Old Man and Woman

We shouldn't overlook the characters. The old man and woman are depicted with such a sweet, weary tenderness. They aren't caricatures. They are lonely people who just want a companion. The way they care for the "scrawny" kitten at the end—feeding it milk and brushing its fur until it grows sleek and beautiful—is a masterclass in showing, not telling, what love looks like.

It’s about transformation.

The kitten doesn't become beautiful because it's "better" than the others. It becomes beautiful because it is seen. Because it is cared for. In a world that currently feels like a loud, vanity-driven shouting match (not unlike the cats on the hill), that message feels more relevant in 2026 than it did in 1928.

How to Share This Book With the Next Generation

If you’re going to read Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág to a kid today, don't just rush through the words.

👉 See also: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Look at the movement. Trace the line of the hills with your finger. Point out how the cats are tucked into every corner of the page. Ask the kid why they think the little kitten stayed quiet while the others were boasting.

Actionable Steps for Collectors and Parents

- Seek out the 1920s/30s editions if you can: The printing quality in some of the older hardcovers captures the depth of the lithography much better than cheap modern paperbacks.

- Visit New Ulm: If you’re ever in Minnesota, Gág’s childhood home is a museum. You can see where the "swirling" hills in her mind actually came from.

- Compare it to "The Funny Thing": This was Gág’s follow-up book. It’s just as weird and involves an "amimal" (not a typo) that eats "gir-uplans."

- Embrace the B&W: Don't be afraid of the lack of color. Use it as a way to talk about how artists create "color" and "mood" using only light and shadow.

Millions of Cats by Wanda Gág remains the longest-running American picture book still in print. That doesn't happen by accident. It happens because Wanda Gág knew that a great story needs a bit of rhythm, a bit of heart, and a healthy dose of the unexpected. It’s a book that respects the intelligence of the child and the eye of the artist. If your home library is missing it, you’re missing a piece of history.

Go find a copy. Read the refrain out loud. Let the "trillions of cats" take over your living room for a few minutes. It’s worth it.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly appreciate Gág's work, examine her diary entries published as Growing Pains. They provide a raw look at her struggle to succeed in the New York art world. Additionally, researching the transition from woodblock printing to lithography in the early 20th century will clarify why the visual texture of this book was considered so revolutionary at its release. Finally, compare the pacing of Gág’s work to modern "calm" picture books to see how her use of white space influenced current minimalist trends in children’s publishing.