It’s the snare drum. That crisp, gated reverb sound that screams 1988, yet the moment Paul Carrack’s soulful voice hits that first line, the decade doesn't matter anymore. You’ve felt it. I’ve felt it. Most of us have spent at least one late night staring at a wall thinking about a conversation we should have had with someone who isn't around to hear it now. Mike and the Mechanics The Living Years isn't just a synth-pop ballad; it’s a universal gut punch disguised as an Easy Listening radio staple.

Most people think this was a Mike Rutherford solo project, but it was really a supergroup of sorts. Rutherford was already a legend from Genesis, but he needed a different outlet. He found it in 1985, but it wasn't until early 1989 that this specific track hit Number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed there because it tapped into a specific kind of grief. Not the loud, screaming kind. The quiet, "I wish I hadn't said that" kind.

The devastating truth behind the lyrics

The song is famously about a father-son relationship, but there’s a layer of irony here that most fans miss. It wasn't written by just one person. It was a collaboration between Mike Rutherford and B.A. Robertson. Here is the kicker: both men had recently lost their fathers, but the lyrics are almost entirely Robertson’s perspective.

He was grappling with the fact that he never truly reconciled with his dad before the end came. It’s brutal. Lines like "I wasn't there that morning when my father passed away" aren't just poetic filler. They are autobiographical facts. Robertson has spoken about the sheer guilt of being "a thousand miles away" when the phone call came. It’s that distance—both physical and emotional—that gives the track its legs.

You see, Rutherford’s father had passed away during the Genesis Invisible Touch tour. He was a conservative, military man—a Captain in the Royal Navy. While they weren't constantly at odds, there was a generational gap that felt like a canyon. That’s the "different languages" the song talks about. It's the struggle of a post-war father trying to understand a rockstar son.

Why the production works (even the choir)

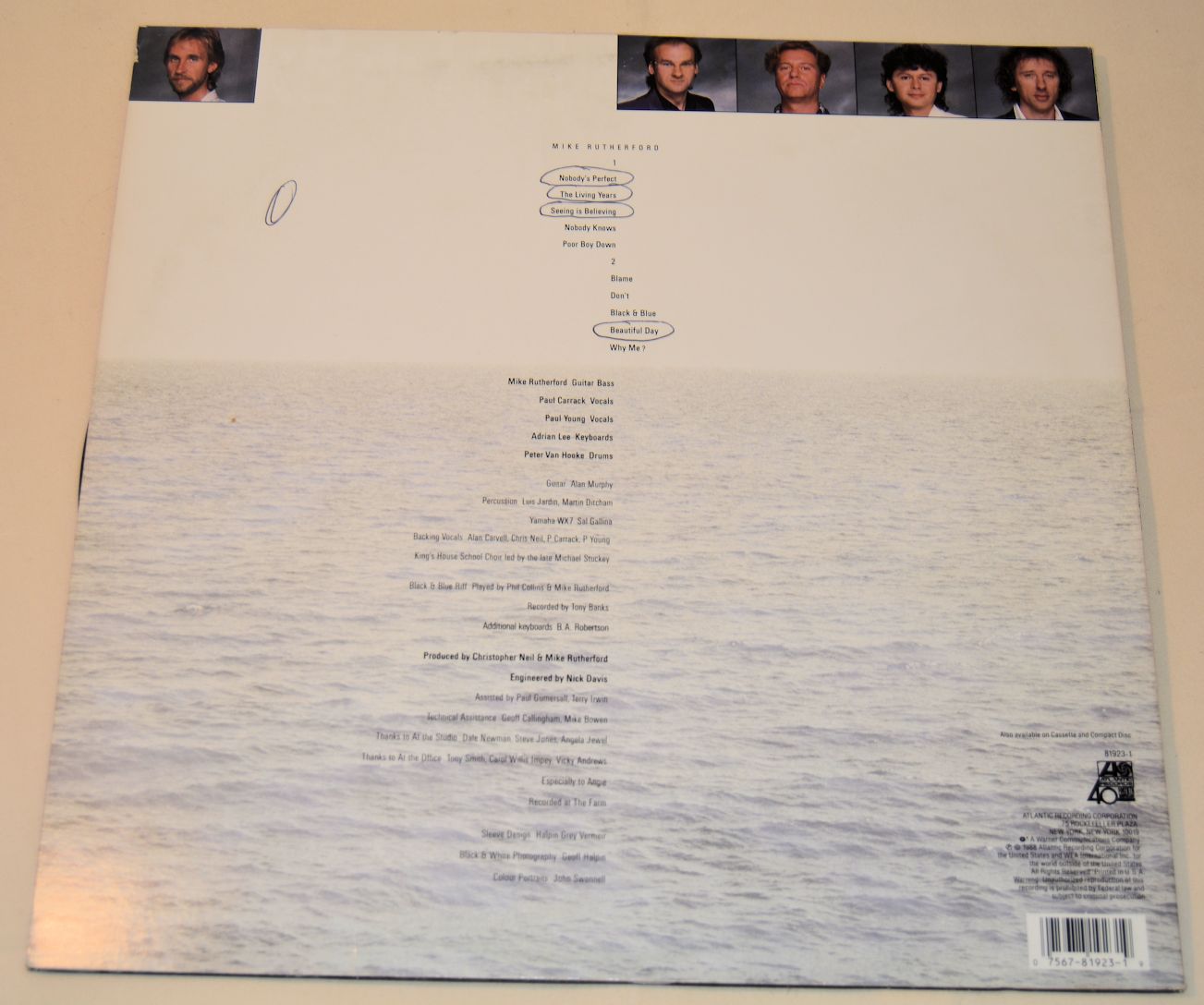

Back in the late 80s, you couldn't throw a rock without hitting a song that used a boy's choir. It was a trope. Usually, it felt cheesy. But on Mike and the Mechanics The Living Years, the inclusion of the choir from King's College School serves a real purpose. It represents the "next generation" mentioned in the lyrics.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

- The song starts with that moody, atmospheric synth.

- Paul Carrack delivers what is arguably the best vocal performance of his career.

- The bridge shifts the tone, moving from personal regret to a broader cycle of life.

Christopher Neil, the producer, made a gutsy call. He kept the arrangement relatively sparse for the first half. He let Carrack’s voice do the heavy lifting. Carrack wasn't even the primary songwriter, yet he sang it with such conviction that people still show up to his solo shows today just to hear him belt out that one high note on "say it loud." Honestly, if anyone else had sung it, the song might have drifted into "Hallmark card" territory. Instead, it feels like a confession.

Common misconceptions about the "Mechanics"

A lot of casual listeners think Mike and the Mechanics was just Mike Rutherford and whoever was available. Not true. The "Mechanics" were a tight unit. You had Paul Carrack (the voice of Ace’s "How Long") and Paul Young (the one from Sad Café, not the "Every Time You Go Away" guy).

Having two world-class vocalists was their secret weapon. While Paul Young handled the rockier, uptempo stuff like "All I Need is a Miracle," Carrack was the surgeon for the emotional ballads. The band wasn't a side project meant to be "Genesis Lite." It was an exploration of blue-eyed soul and sophisticated pop.

Some critics at the time called it "Calculated." They thought the emotion was manufactured for radio play. But you can't fake the reaction this song gets. When it played, people called into radio stations just to talk about their dads. It triggered a mass therapy session across the FM dial. That's not calculation. That's resonance.

The 1989 cultural shift

To understand why this song exploded, you have to look at what else was happening in 1989. We were at the tail end of the "greed is good" decade. Pop music was largely shiny, plastic, and loud. Then comes this somber, mid-tempo track about death and the failure of communication.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

It stood out because it was vulnerable. It gave men, specifically, permission to feel something other than "tough." The lyrics talk about "the spirit left blindly," which is a pretty heavy concept for a song sandwiched between Paula Abdul and Bobby Brown on the charts.

The irony of the "New Born Baby"

The final verse of Mike and the Mechanics The Living Years mentions a newborn baby reaching out for the "old man's hand." This isn't just a metaphor for the circle of life. In a strange twist of timing, B.A. Robertson’s son was born just months after his father died.

That duality—the arrival of new life while mourning the old—is why the song doesn't leave you feeling completely depressed. It’s bittersweet. It suggests that while we can't fix the past, we have a second chance with the people who are still here.

People often ask if Mike Rutherford regrets not being closer to his father. In interviews, he’s been pretty candid. He says they were "getting there." They were starting to find common ground. But the song serves as a warning for everyone else: don't wait for "getting there." Get there now.

What we get wrong about the message

Is it a song about death? Sorta. But more accurately, it’s a song about communication.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

We live in an age where we are constantly "connected." We have DMs, texts, emails, and comments. Yet, how much of it is actually "saying it loud and saying it clear"? We hide behind screens and emojis. The "living years" refers to the window of opportunity we have to be honest with each other. Once that window closes, the silence is deafening.

The song argues that "we all agree that we've agreed" as a way to avoid the hard conversations. We pretend everything is fine to keep the peace, but that peace is hollow. It's a "bitter leaf" that we swallow.

How to apply the "Living Years" philosophy today

If you’re listening to this track in 2026, the tech has changed but the ego hasn't. We still hold grudges over things that won't matter in ten years. We still let pride get in the way of an apology.

- Identify the "Unsaid": Who is that one person you have a "strained" relationship with? Is it actually strained, or are you both just waiting for the other to blink first?

- Strip the jargon: Don't send a long, "therapeutic" text. Just talk. Like the song says, use "the living years" to actually speak.

- Acknowledge the gap: You don't have to agree with your parents or your kids on everything. You just have to acknowledge that you're both looking at the same world through different lenses.

The legacy of Mike and the Mechanics isn't just a collection of gold records. It’s the fact that three decades later, someone is going to hear that song on a classic hits station, pull their car over, and finally make the phone call they’ve been putting off for five years. That is the power of a song that stays in the living years.

Actionable Insight: Next time you hear those opening synths, don't just hum along. Take it as a cue. If there is a conversation you have been avoiding because it feels "awkward" or "too late," remember that "too late" only happens when the breathing stops. Use the time you have to bridge the gap, even if it's just to say you're listening.