It was 1999. Kevin Costner was still arguably the king of the sweeping, slightly tragic American epic, and Robin Wright was transitioning from her Princess Bride innocence into something much more weathered and complex. Then there was the message in a bottle film, a movie that critics absolutely loved to hate but audiences couldn't stop talking about. If you grew up in the late nineties, you remember the posters. The blue hues. The crashing waves of the Outer Banks. The feeling that maybe, just maybe, a piece of paper in a glass jar could actually change your life.

People forget how much of a gamble this was. Warner Bros. put a lot of chips on an adaptation of a Nicholas Sparks novel back when Sparks wasn't even a "genre" yet. This was only his second published book. Before The Notebook made everyone sob in 2004, this movie had to prove that old-school, tear-jerker romantic dramas could still pull numbers at the box office. And it did. It pulled in nearly $120 million globally. Honestly, though, the legacy of the film isn't about the money. It’s about that specific, localized grief that Costner captures so well.

The plot is simpler than you remember (and weirder)

Theresa Osborne, played by Wright, is a researcher for the Chicago Tribune. She’s jogging on a beach in Cape Cod when she finds it. A corked bottle. Inside is a letter so poetic and gut-wrenching it feels like it was written in another century. "You are my true north," it says. It’s signed simply, "G."

She doesn't just read it and move on. She becomes obsessed. This is where the movie shifts from a romance into a sort of investigative drama. Through her job's resources, she tracks the typewriter ribbon and the paper stock. It leads her to North Carolina. To Garret Blake.

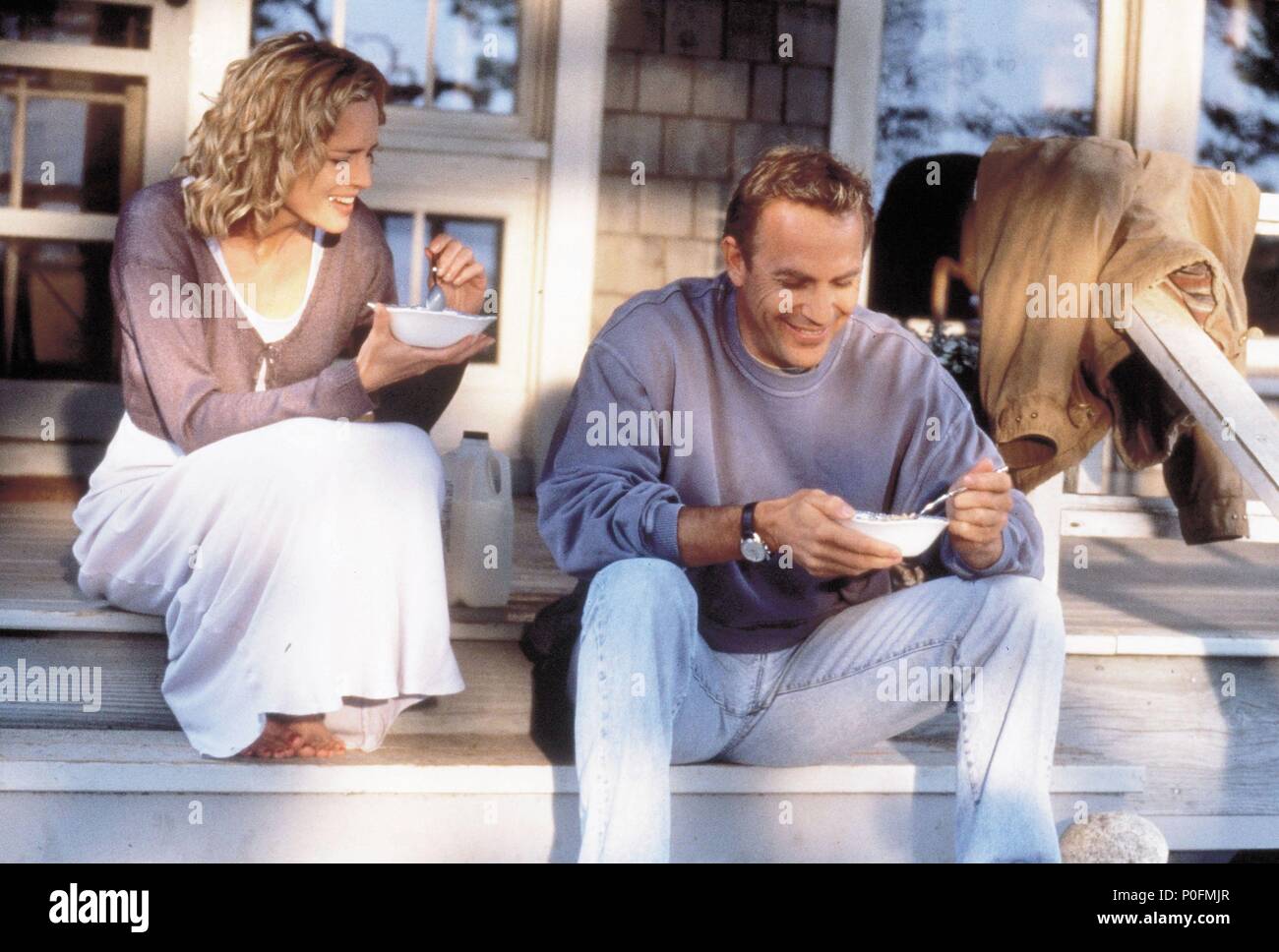

Garret is a shipbuilder. He’s grieving his late wife, Catherine, and he’s doing it in the most self-destructive way possible: by staying completely frozen in time. When Theresa shows up, she doesn't tell him she found the letters. She just hangs out. She embeds herself in his life. Looking back, it’s a little creepy, right? In 2026, we’d call that "catfishing Lite," but in the context of a 1999 romance, it was framed as destiny.

Paul Newman stole every single scene

We have to talk about Dodge Blake. Paul Newman played Garret’s father, and frankly, he’s the best part of the entire message in a bottle film. By the late nineties, Newman had reached this level of effortless cool where he didn't even seem to be acting. He was just being.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

Dodge is the voice of reason. He’s a former alcoholic who’s watched his son rot away in a house full of a dead woman's clothes. There’s a specific scene where Dodge tells Garret to choose between the past and the future. It’s not flashy. There are no soaring violins. It’s just two men in a kitchen, but it carries more weight than any of the scenes on the boats. Newman brought a grit to the film that saved it from becoming too "saccharine." He reminded us that grief isn't just crying; it's being grumpy, tired, and stuck.

Why the ending caused a literal uproar

If you haven't seen it, stop reading. Seriously.

The ending of this movie is notorious. In most romances, the couple overcomes the "big secret"—in this case, Theresa’s deception about the letters—and they live happily ever after. Nicholas Sparks doesn't play that way. Garret finally finishes the boat he was building for his late wife, names it after her, and sets sail. He gets caught in a storm. He dies trying to save someone else.

I remember people leaving the theater genuinely angry. You spend two hours watching two broken people find each other, only for one of them to get swallowed by the Atlantic Ocean? It felt cruel. But that’s actually why the movie stays in your head. It refuses to give you the easy out. It argues that the "message in the bottle" wasn't about a long life together; it was about the act of reaching out one last time before the end.

The Outer Banks as a character

The film was mostly shot in Maine (oddly enough, standing in for the Carolinas) and North Carolina. The cinematography by Caleb Deschanel—who is a legend, by the way—is breathtaking. He shot it with these long, anamorphic lenses that make the ocean look infinite and the people look tiny.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

- The house: Garret’s house wasn't a set. It was a real structure that felt lived-in.

- The boats: The Happenstance and the Catherine were actual wooden schooners.

- The weather: They used real storms and grey skies, avoiding the "sunny beach" trope.

This visual language created an atmosphere of isolation. You really felt like these characters were on an island, even when they weren't.

The critics were wrong about the "cheese" factor

Roger Ebert gave the movie two stars. He said it was "contrived." He wasn't wrong, technically. The chances of finding a bottle in the ocean and then finding the exact person who wrote it are astronomical. But the message in a bottle film wasn't trying to be a documentary. It was an exploration of how we use objects to tether ourselves to people who are gone.

Theresa used the letter to find a man. Garret used the boat to stay close to his wife. Dodge used his house to keep an eye on his son. It’s a movie about "relics."

Modern legacy and where to watch

Today, you can find the film on most major streaming platforms like Max or Amazon Prime. It’s often grouped with A Walk to Remember or The Lucky One, but it feels different from those. It’s more adult. It’s slower. It’s interested in the logistics of rebuilding a life after thirty, not just teenage angst.

There’s a specific texture to nineties filmmaking—the film grain, the lack of CGI, the reliance on two people just talking in a room—that makes this movie feel like a time capsule. It’s a reminder of a time when "adult dramas" could be blockbusters.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Actionable ways to engage with the film's themes

If you're revisitng this classic or watching it for the first time, don't just let the credits roll. There are ways to actually take the "vibe" of the movie and apply it to real life.

Start a physical correspondence.

We live in an era of "ghosting" and DMs. There is something profoundly different about handwriting a letter. You don't have to throw it in the ocean, but sending a physical note to someone you care about creates a permanent record of your thoughts. It’s a "message in a bottle" for the digital age.

Visit the filming locations.

If you're a fan of the aesthetic, head to Wilmington, North Carolina, or New Harbor, Maine. These spots still carry that misty, coastal atmosphere. The "Garret Blake" house in Maine is a private residence, but the surrounding coastline is public and looks exactly like it did in 1999.

Explore the Nicholas Sparks bibliography in order.

Most people jump straight to The Notebook. If you want to understand the evolution of this genre, read Message in a Bottle first, then watch the film, then move to A Walk to Remember. You’ll see how the themes of "divine intervention" and "tragic timing" developed over time.

Watch for the technical details.

On your next viewing, ignore the romance for a second. Look at the way Deschanel uses light. Notice how the color palette shifts from the cold, industrial blues of Chicago to the warm, sandy ochres of the coast. It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling that most modern romances ignore in favor of "bright and poppy" lighting.

The message in a bottle film isn't perfect. It’s long, it’s arguably too sad, and the central lie is hard to swallow. But in a world of 15-second TikToks, there’s something deeply satisfying about a movie that takes its time to let a character just sit on a porch and miss someone. It’s a movie that respects the weight of a letter. And sometimes, that’s all you really need on a Sunday afternoon.