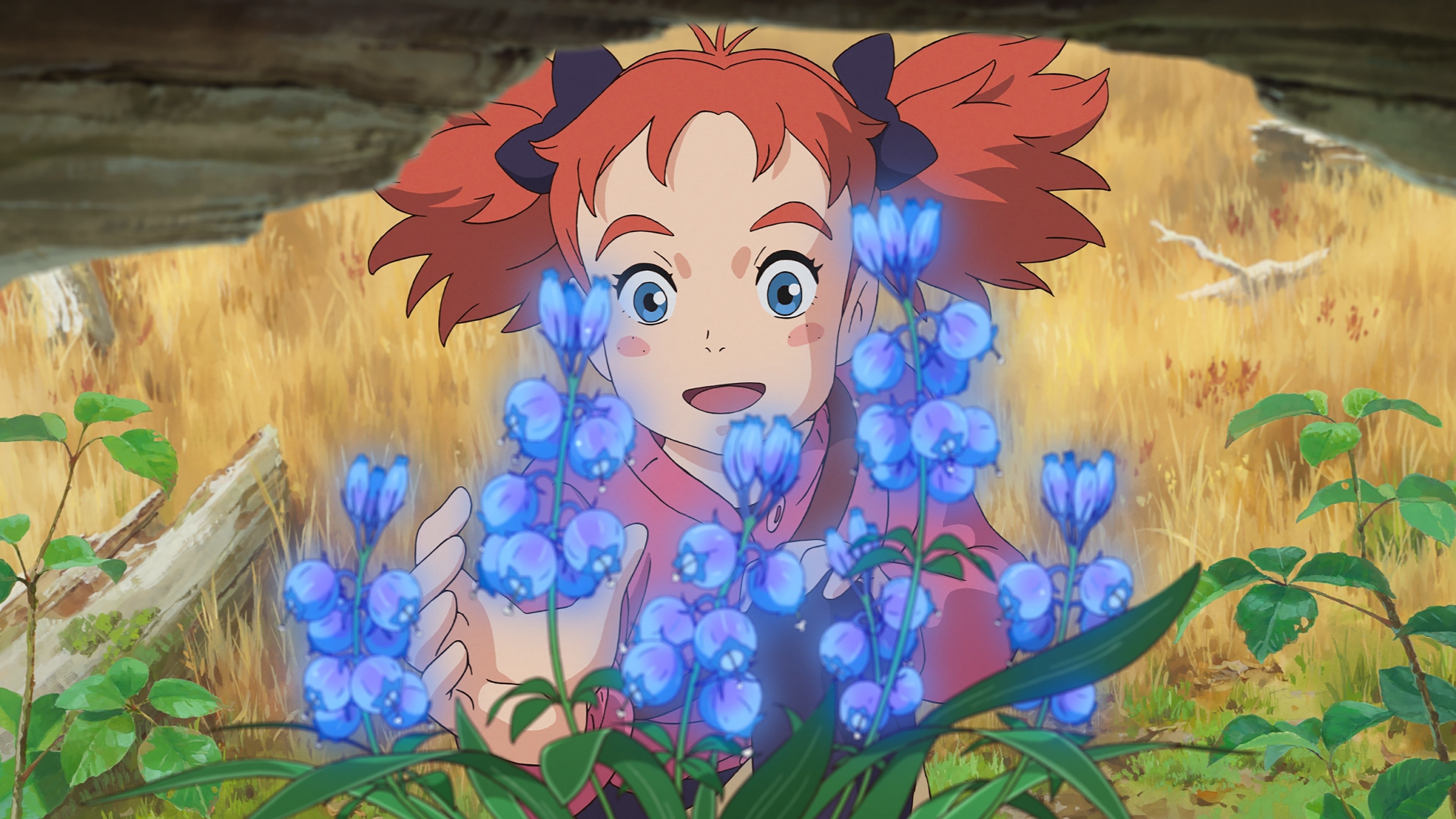

It’s that specific blue. You know the one—a glowing, deep electric indigo that looks like it was squeezed directly out of a dream and onto an animation cell. When Mary and the Witch's Flower first hit theaters, people didn't just see a movie; they saw a ghost. Or maybe a rebirth. Honestly, it’s hard to tell the difference when you’re looking at the first feature film from Studio Ponoc, the house built by the survivors of Studio Ghibli’s temporary shuttering in 2014.

Mary Smith is a mess. She’s got frizzy red hair that she hates, she’s clumsy as all get-out, and she’s stuck in the British countryside with her Great-Aunt Charlotte. It’s boring. Then she follows a cat into the woods, finds a "Fly-by-Night" flower, and suddenly she's whisked away to Endor College, a school for magic hidden in the clouds. If this sounds like Harry Potter, you're not wrong, but it’s Harry Potter filtered through a lens of lush, hand-drawn environmentalism and a very specific Japanese obsession with English children’s literature.

The Ghibli DNA is everywhere

You can’t talk about this film without talking about the elephant in the room: Studio Ghibli. When Hayao Miyazaki announced his (first) retirement and Ghibli paused production, producer Yoshiaki Nishimura and director Hiromasa Yonebayashi didn't just quit. They founded Studio Ponoc. Yonebayashi brought the same sensibilities he used for The Secret World of Arrietty and When Marnie Was There to this project.

The result?

It feels familiar. Maybe too familiar for some critics, but for fans who were mourning the end of an era, it was a lifeline. The way the clouds move, the hyper-detailed kitchen scenes, the tactile nature of every broomstick and potion bottle—it’s all there. But there’s a frantic energy here that Miyazaki usually avoids. It’s more kinetic.

What actually happens in Mary and the Witch's Flower

Based on Mary Stewart’s 1971 book The Little Broomstick, the plot is pretty straightforward. Mary finds the flower, which grants her temporary magical powers. She ends up at Endor College, where the headmistress Madam Mumblechook and the resident scientist Doctor Dee (who looks like a steampunk nightmare) realize she’s found the rare Fly-by-Night. They want it. They want it bad. They’re obsessed with a "transformation" experiment that went horribly wrong years ago, and they need the flower’s power to try again.

The stakes get high fast. It’s not just a school story; it’s a story about the ethics of power and the danger of trying to bypass hard work with a "shortcut" like a magical flower.

🔗 Read more: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

Mary isn't a chosen one. She's just a kid who happens to be in the right place at the wrong time with the right plant. That makes her relatable. She’s not special because of destiny; she’s special because she decides to fix the mess she accidentally helped create.

Why the animation matters in 2026

In an era where AI-generated images are cluttering up our feeds and 3D CGI has become the default for big-budget animation, Mary and the Witch's Flower stands out as a testament to the "handmade." The background art, led by the late, great Kazuo Oga’s influence, is breathtaking. These aren't just settings; they are paintings you want to step into.

The film uses roughly 1,200 cuts. That is a massive amount of manual labor. Each frame of the "transformation" sequence, where animals are fused together in a shimmering, terrifying blob of magic, required insane levels of coordination between the animators. It’s messy. It’s fluid. It’s something a computer struggle to replicate because it relies on "intentional imperfections" that give hand-drawn art its soul.

The "Shortcut" Metaphor

Think about the flower. The Fly-by-Night gives Mary instant, god-like power, but it’s temporary and dangerous. It’s a metaphor for pretty much anything in life where we try to skip the struggle. Doctor Dee and Madam Mumblechook represent the dark side of that—science and magic without a moral compass.

Honestly, it’s kinda ironic. Studio Ponoc was trying to prove they could do it on their own, without the "magic" of Miyazaki’s direct involvement. They were under immense pressure to live up to a legacy that felt impossible to match. In a way, the movie is about the studio itself: can you make magic without the old masters?

The answer they found was a resounding "sorta." It’s a beautiful film, even if the script feels a little thin in the second act. The pacing at Endor College moves so fast you barely have time to breathe, which is a stark contrast to the slow, meditative "Ma" (the vacuum or space between action) that Ghibli is famous for.

💡 You might also like: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

Real-world impact and the legacy of Mary Stewart

Mary Stewart’s estate was reportedly very happy with the adaptation, which is rare for British authors whose work gets the anime treatment. Usually, things get lost in translation. But Yonebayashi kept the "Britishness" of the source material intact—the tea, the damp gardens, the specific way Aunt Charlotte speaks.

It’s worth noting that the film didn't just do well in Japan. It had a massive international rollout, proving that there is a global hunger for this specific style of storytelling. It grossed over $42 million worldwide, which for an indie studio’s first outing, is nothing short of a miracle.

Common misconceptions about the film

Some people think this is a sequel to Kiki's Delivery Service. It's not. I get why you'd think that—girl on a broom, black cat, magical mishap. But Mary is a different beast entirely. Kiki is about the struggle of growing up and finding your place; Mary is about the responsibility of power and the bravery of being "ordinary."

Another weird myth is that Miyazaki secretly directed some of it. He didn't. In fact, he famously refused to watch it while it was in production because he didn't want to influence them. When he finally did see it, he reportedly just said, "You worked hard," which is basically the highest praise you’ll ever get from that man.

How to actually watch it and what to look for

If you’re sitting down to watch it for the first time, or maybe the fifth, pay attention to the lighting. The way the light changes when Mary enters the misty forest versus the sterile, bright laboratory of Doctor Dee tells the whole story without a single word of dialogue.

- Watch the subbed version first. The Japanese voice acting (especially Hana Sugisaki as Mary) captures the frantic, high-pitched energy of the character better than the dub, though the English cast (Ruby Barnhill and Kate Winslet) is genuinely great too.

- Look at the edges of the frame. Studio Ponoc fills the corners with tiny details—strange creatures, moving plants, and peculiar magical artifacts—that you’ll miss if you only look at the center.

- Don't compare it to Spirited Away. That's a trap. Compare it to a Saturday morning adventure. It’s meant to be fun and visually stimulating, not a deep philosophical treatise on the human condition.

Actionable steps for the true fan

If you've already seen the movie and want to go deeper, there are a few things you should actually do rather than just scrolling for more trivia.

📖 Related: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

Read "The Little Broomstick" by Mary Stewart. It’s a quick read, but seeing where the animators diverted from the text is fascinating. The book is much more grounded in traditional English folklore, whereas the movie turns the climax into a high-stakes action set piece.

Check out the "Art of Mary and the Witch's Flower" book. If you’re into illustration or just want to see the sheer scale of the background paintings, this book is essential. It breaks down the color palettes used for different emotional beats.

Follow Studio Ponoc’s newer work. They followed up Mary with Modest Heroes, a collection of three short films, and more recently The Imaginary. Watching their progression shows how they are slowly stepping out of Ghibli’s shadow and finding their own, slightly weirder voice.

Visit the Ghibli Museum (if you can). While it’s technically Ghibli, the crossover in staff means the exhibits on hand-drawn animation techniques apply directly to how Mary was made. Seeing the physical layers of a background painting in person changes how you view the screen.

Ultimately, the film is a bridge. It bridges the gap between the golden age of 20th-century anime and whatever the future of hand-drawn features looks like. It’s a bit messy, extremely beautiful, and filled with a kind of earnestness that feels increasingly rare. You don't need a magical flower to see why it matters; you just need to look at the screen and appreciate the work of several hundred artists who refused to let a medium die.