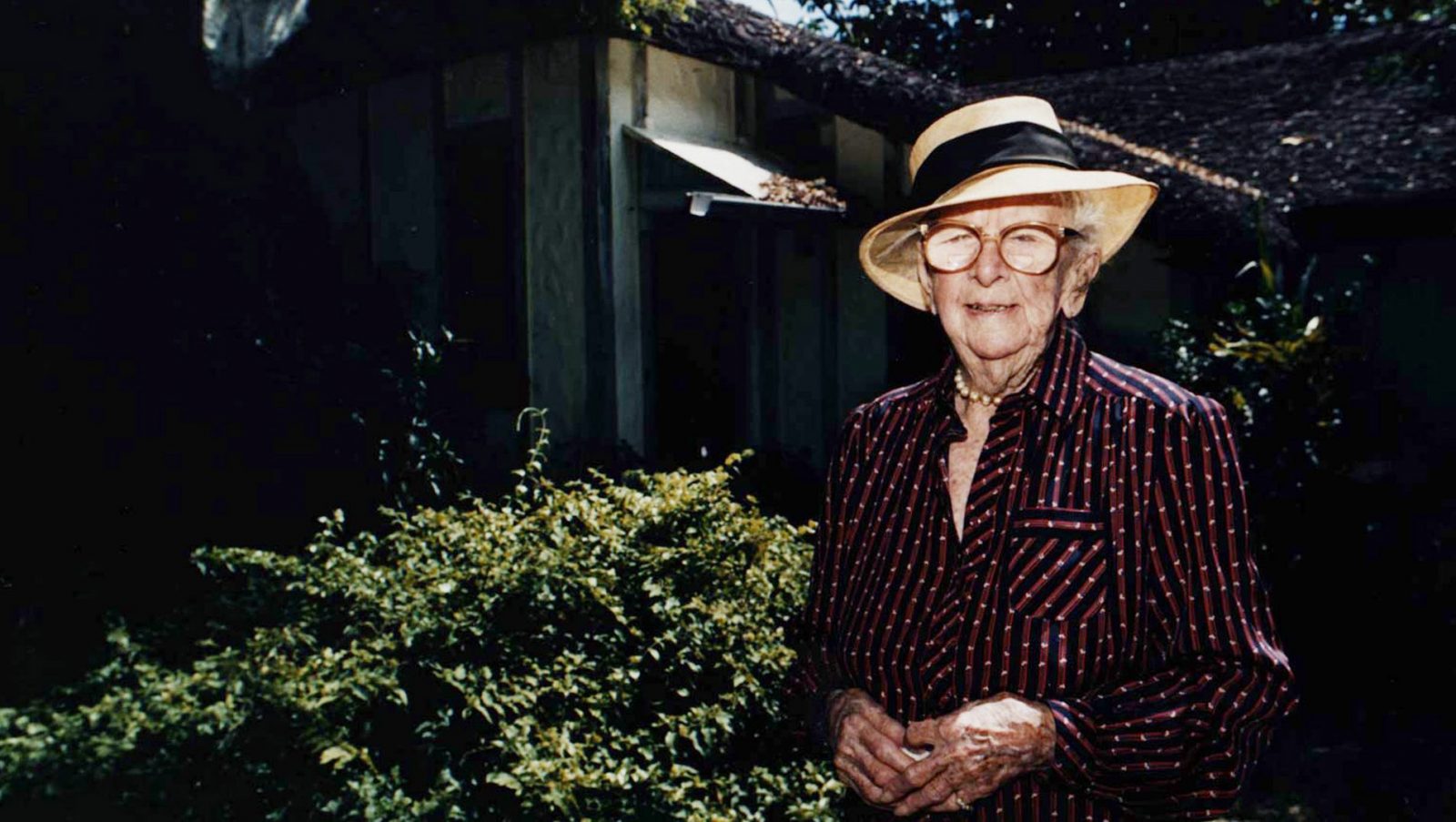

You’ve probably seen the name on a high school or a highway. Maybe you’ve heard the phrase "River of Grass." But if you think Marjory Stoneman Douglas was just some sweet old lady who liked birds and wore floppy hats, you’ve got it all wrong. She was a fighter. Honestly, she was a total powerhouse who didn't even start her most famous work until she was at an age when most people are picking out retirement homes.

Marjory Stoneman Douglas environmentalist legend wasn't born in the swamp. She was a Minneapolis girl who moved to Miami in 1915 to escape a bad marriage and find her father. What she found instead was a frontier town and a massive, misunderstood wilderness that everyone else wanted to destroy. Back then, the Everglades weren't seen as a treasure. People called them a "useless swamp." They wanted to drain every drop of water to plant sugar cane and build houses. Marjory saw something else.

📖 Related: Exactly how long ago was 3 30pm and why your brain keeps losing track

She saw a river.

The Book That Changed Everything

It’s hard to overstate how much The Everglades: River of Grass shifted the American mindset. Published in 1947, the same year Everglades National Park was dedicated, it basically told the world: "Hey, you're killing a masterpiece."

Before this book, the Everglades were just a place to get eaten by mosquitoes or lost in the sawgrass. Marjory spent five years researching the hydrology and the history. She worked with scientists like Garald Parker to prove that the Everglades weren't a stagnant pond. They were a slow-moving, shallow river, sixty miles wide and a hundred miles long.

The opening line is iconic: "There are no other Everglades in the world."

🔗 Read more: How Much Is One Centimeter? The Weird History and Real-World Scale of the Metric Standard

She wasn't just being poetic. She was being literal. If we lost this, it was gone forever. The book sold out its first printing in a month. People finally understood that the water they drank in Miami came from the very place they were trying to pave over. It’s kinda wild how one woman with a typewriter could take on the massive machinery of the Army Corps of Engineers and the sugar industry, but that’s exactly what happened.

Activism at Age 79? Seriously.

Most people start slowing down in their late 70s. Not Marjory. In 1969, when she was 79 years old, she founded Friends of the Everglades. Why? Because developers wanted to build a massive "Jetport"—a huge international airport—right in the middle of the Glades.

She was tiny, barely five feet tall, and her eyesight was failing. But she was a terror at public meetings. She once told a room full of hostile developers, "I can’t see you, but I know you’re there." She didn't care about being liked. She cared about being right.

The Jetport was eventually stopped, which is one of the biggest wins in environmental history. If that airport had been built, the entire ecosystem would have collapsed. No more wood storks. No more Florida panthers. Just the sound of jet engines and the smell of fuel.

Why She Was Different

- She was a journalist first. She knew how to use the media to embarrass politicians.

- She was a feminist and a civil rights advocate. She fought for women’s suffrage and better sanitation in Black neighborhoods long before it was popular.

- She was relentless. She lived to be 108. Let that sink in. She was still giving interviews and pushing for restoration in her second century of life.

What Most People Get Wrong

There’s a common myth that she was some kind of "nature girl" who spent all her time hiking through the muck. Truthfully? She wasn't a big fan of the outdoors in a physical sense. She once famously said, "To be a friend of the Everglades is not necessarily to spend time wandering around in them." She hated the heat and the bugs just as much as anyone else.

Her connection was intellectual and moral. She understood that humans need nature to survive, not just for "pretty views," but for the actual water supply. She was a skeptic and a dissenter. She didn't trust the government to do the right thing unless she was breathing down their necks.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton gave her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She was 103 then. She didn't use the moment to talk about her legacy; she used it to remind everyone that the work wasn't finished. She knew that the "Marjory Stoneman Douglas Everglades Protection Act" of 1991 was flawed. She called it out for being too weak on polluters. She was a "nuisance where it counts," which is exactly what she advised others to be.

The Legacy We’re Living With

The Everglades are still in trouble. We’ve diverted so much water and added so much phosphorus from fertilizer that the balance is precarious. But without the work of a dedicated marjory stoneman douglas environmentalist spirit, there wouldn't be an Everglades left to save.

Today, the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) is the largest environmental restoration project in history. It’s expensive. It’s slow. It’s frustratingly political. But it exists because Marjory made the "River of Grass" a household name.

👉 See also: Finding Miso Ramen Jersey City NJ: Why Most People Are Looking in the Wrong Spot

She died in 1998, and her ashes were scattered in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness Area. She didn't want a big monument. She wanted the water to keep flowing.

Actionable Ways to Honor Her Today

If you want to actually do something instead of just reading about history, here’s how you can channel your inner Marjory.

First, get educated on where your water comes from. In Florida, that’s the Biscayne Aquifer, which is recharged by—you guessed it—the Everglades. If you live elsewhere, find your local watershed.

Second, become a "nuisance." Write to your local representatives about land use. Marjory didn't save the Glades by being "nice"; she saved them by being informed and loud.

Third, support grassroots organizations. Friends of the Everglades is still around. They don't have the billion-dollar budgets of the sugar lobbies, but they have the same grit Marjory had.

Finally, read her book. It’s not a dry textbook. It’s a love letter to a landscape that most people tried to ignore. It’ll change how you look at a "swamp" forever.

To make an impact, start by visiting the Friends of the Everglades website to see their current legislative priorities. You can also look up the Everglades Foundation for data-driven reports on water quality that you can cite when talking to your local officials. The best way to keep her legacy alive is to refuse to let the "River of Grass" become a footnote in history.