When Marilyn Monroe died in August 1962, the world stopped. But for a silver-haired artist in a cluttered New York studio, the tragedy was a starting gun. Andy Warhol didn't know Marilyn. He never met her. He didn't even use a fresh photograph of her to create what would become the most expensive piece of 20th-century American art. He just bought a publicity still from her 1953 film Niagara, cropped it, and changed the world.

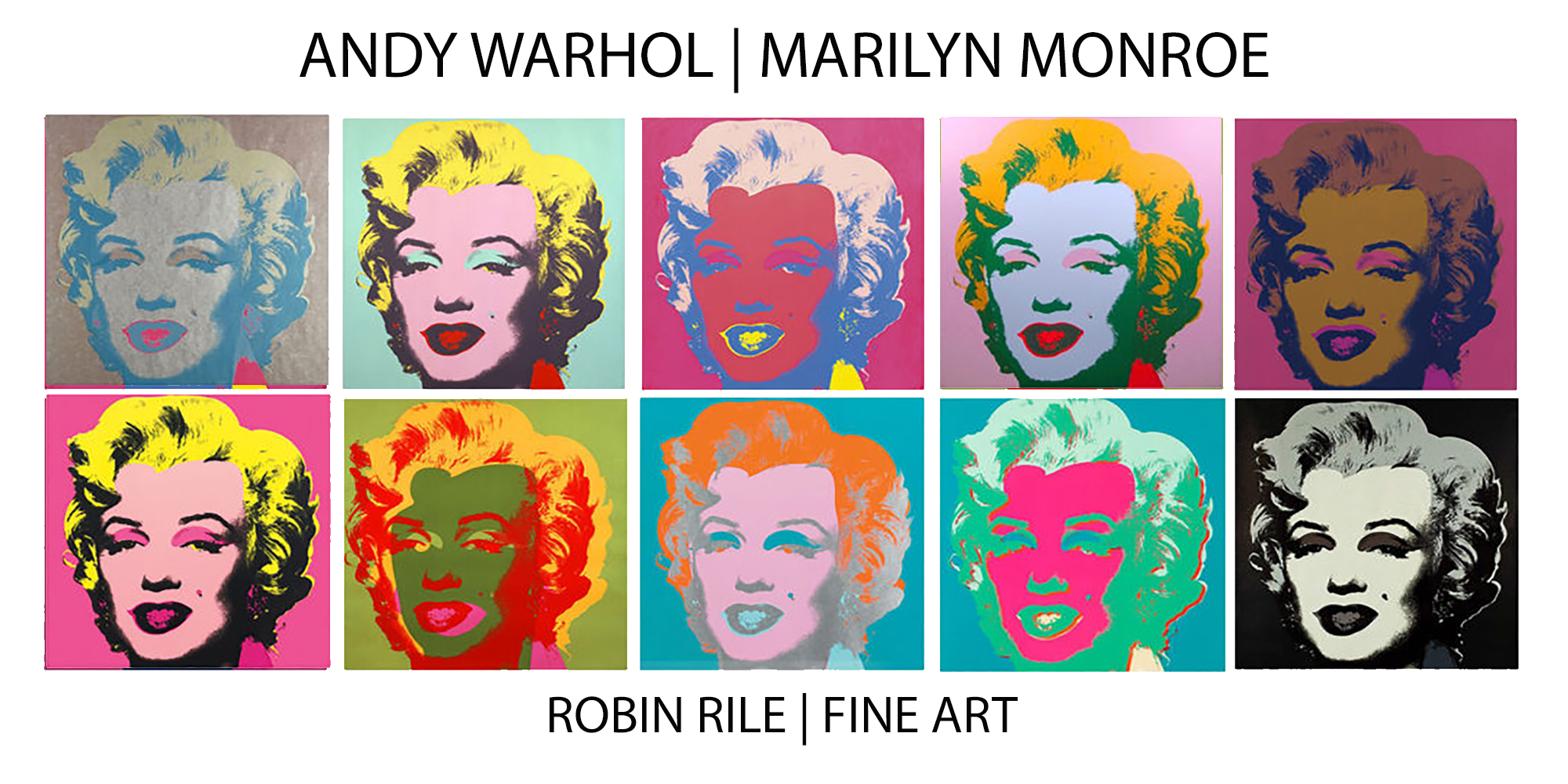

It's weird, right? We think of Marilyn Monroe Andy Warhol as this inseparable duo, a marriage of pop culture and high art that feels like it was always meant to be. Honestly, it was a fluke of timing and obsession. Warhol was obsessed with the idea of the "machine." He wanted to be one. He wanted to make art that looked like it came off an assembly line, which is exactly why he turned to silkscreening. It’s a messy, industrial process. If you’ve ever looked closely at a Marilyn Diptych, you’ll see the ink is blotchy. Some faces are ghostly; others are caked in neon pink. That wasn't an accident. Or maybe it was, and he just leaned into the "error" of it all.

The Shot Blue Marilyn and the $195 Million Scandal

Let's talk about the money. People lose their minds over the prices. In 2022, Shot Sage Blue Marilyn sold at Christie’s for roughly $195 million. That is a staggering amount of cash for a piece of linen covered in acrylic and silkscreen ink. But why?

It’s about the story. In 1964, a performance artist named Dorothy Podber walked into Warhol’s "Factory" and asked if she could shoot his new paintings. Warhol, thinking she meant "photograph," said sure. Podber pulled out a revolver and fired a bullet right through the stack of Marilyn foreheads. Warhol didn't throw them away. He just renamed them the "Shot" series. That kind of grit and weirdness is why Marilyn Monroe Andy Warhol remains a titan in the auction world. You aren't just buying a face; you're buying a piece of 1960s New York chaos.

The image itself—that cropped smile, the heavy eyelids—was originally a black-and-white promotional photo. Warhol stripped away the humanity. He gave her yellow hair that looks like a cheap wig and turquoise eyeshadow that screams "department store sale." By doing this, he turned a woman into a brand. He recognized that by 1962, Marilyn Monroe wasn't a person to the public anymore. She was a product.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Why We Can't Look Away

Warhol’s genius was his cynicism. He knew we consume celebrities the same way we consume soup. His Campbell’s Soup Cans and his Marilyns are basically the same thing. They represent mass production.

Think about the Marilyn Diptych at the Tate Modern. On the left side, it’s all bright, garish colors. It’s the "Marilyn" of the silver screen—the blonde bombshell, the icon, the mask. On the right side, the images are black and white, and they start to fade. They blur. They disappear into a grainy mess of ink. It’s a literal representation of a human being being erased by their own fame. It’s haunting. It’s also incredibly simple. Warhol wasn't a guy for deep, philosophical monologues. He once said, "If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it."

I think he was lying. There’s a lot behind it. He was a shy, gay, Catholic man from Pittsburgh who was terrified of death. By painting Marilyn over and over again, he was trying to make her immortal. And it worked. We don't remember the real Norma Jeane Mortenson half as well as we remember the neon-pink Warhol version.

The Silk Screen Process: Art or Copying?

Critics at the time hated him. They said he was a "business artist." They weren't wrong, but they missed the point. Warhol used a commercial technique to comment on a commercial world.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

The process went like this:

- Take a photo.

- Transfer it to a fine mesh screen.

- Force ink through the screen onto a canvas.

Because he did it by hand, every "copy" was slightly different. One might have a smudge on the lip. Another might have the registration slightly off, so her hair doesn't line up with her head. This is the "human" part of Marilyn Monroe Andy Warhol. It’s the imperfection of the machine. It’s the crack in the celebrity veneer.

The Cultural Aftermath

You see this everywhere now. Every time you see a stylized portrait on Instagram or a filtered photo that pops with saturated color, you're seeing Warhol's ghost. He predicted the "15 minutes of fame" thing, but more importantly, he predicted that we would eventually care more about the image of a thing than the thing itself.

Marilyn was his greatest subject because she was already a construction. She had spent a decade crafting a persona—the voice, the walk, the look. Warhol just took that construction and flattened it onto a canvas. He made it permanent.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Some people find it exploitative. They argue that Warhol used a woman’s tragic death to make a buck. He started the series just weeks after her overdose. It was "news-cycle art" before the internet existed. But art has always been a bit parasitic, hasn't it? He captured the collective mourning of a nation and turned it into an icon.

How to Appreciate a Warhol Marilyn Today

If you ever get the chance to see one in person, don't just look at the colors. Step to the side. Look at the texture of the paint. Notice how thick the ink is in some places and how thin it is in others.

- Look for the registration errors. Check if the lips align with the color underneath. This tells you about the speed at which it was produced.

- Compare the palettes. The gold Marilyn (housed at MoMA) feels like a religious icon, like a Byzantine Madonna. The neon ones feel like a Times Square billboard.

- Consider the scale. Most of these are larger than life. They are meant to dominate the room, just like she dominated the screen.

There is a weird tension in his work. It’s cold but emotional. It’s cheap but worth millions. It’s Marilyn, but it’s not.

To really understand the impact, you have to realize that Warhol didn't just paint a celebrity. He painted a ghost. By the time the ink was dry, the woman was gone, but the image was everywhere. That is the lasting legacy of the Marilyn Monroe Andy Warhol connection. It’s the moment art stopped being about "truth" and started being about "fame."

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world or even start a collection of your own—even if you don't have $200 million—here is what you should actually do:

- Research the Sunday B. Morning prints. These are unauthorized but high-quality screens made using the original Warhol designs and colors. They offer a way to own the "look" of a Warhol without the museum-level price tag.

- Visit the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. It is the largest museum in North America dedicated to a single artist. Seeing the progression of his work from shoe advertisements to the Marilyns puts everything in perspective.

- Study the "Niagara" publicity still. Compare the original black-and-white photo by Gene Korman to Warhol’s crops. It’s a masterclass in how much power a simple crop can have over the viewer's focus.

- Read "The Philosophy of Andy Warhol." If you want to understand the man behind the screen, his own writing (though often ghostwritten or dictated) captures his unique, detached view of celebrity culture.

Understanding this work requires looking past the bright colors. It's about seeing the machinery of fame and how it consumes the people we claim to love. Warhol didn't just paint Marilyn; he archived her. And in doing so, he made sure we would never be able to forget her—or him.