Geography is destiny. You’ve probably heard that before, but nowhere is it more brutally true than in the Korean Peninsula between 1950 and 1953. When you look at maps of the Korean War, you aren't just looking at ink on paper or pixels on a screen. You’re looking at a three-year-long accordion of human suffering that squeezed up and down a rugged, mountainous spine.

It's messy.

Honestly, if you look at a map from July 1950 and compare it to one from July 1953, they look eerily similar. Both show a line cutting the peninsula roughly in half. But the story of how we got from one "middle line" to the other is a chaotic mess of retreat, surprise landings, and some of the coldest battles in military history.

The Pusan Perimeter: Backs to the Sea

By August 1950, the map was terrifying for the UN forces. After the North Korean People's Army (NKPA) crossed the 38th Parallel in June, they basically steamrolled south. They had Soviet T-34 tanks; the South had almost nothing that could stop them.

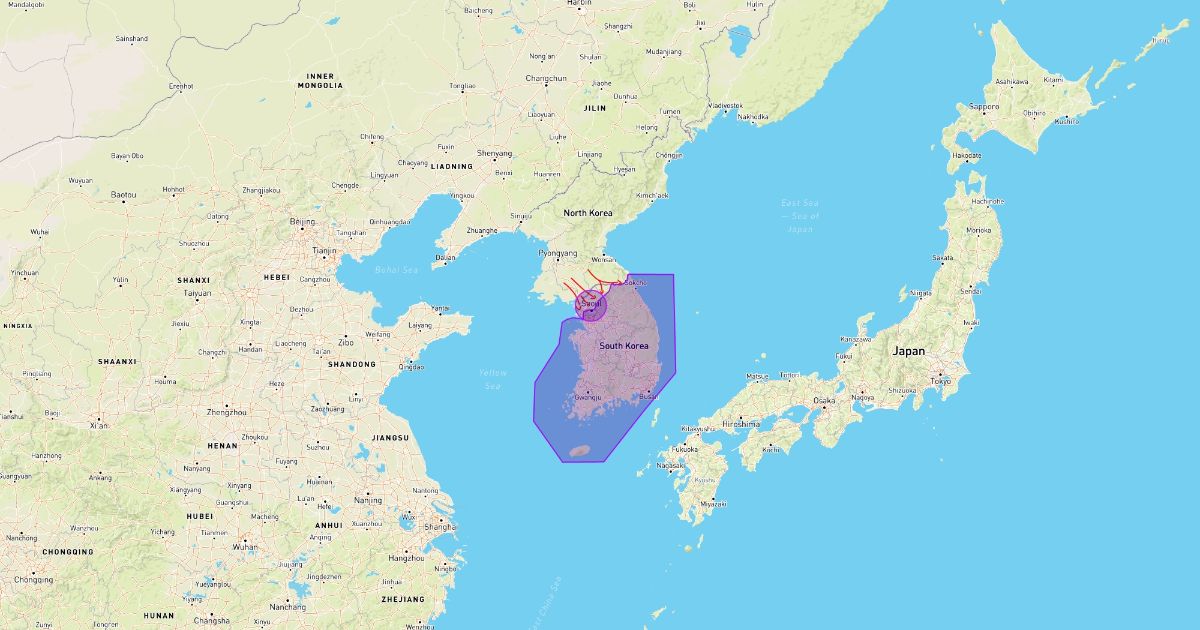

Look at a map of this period and you'll see a tiny, cramped pocket in the southeast corner of Korea. This was the Pusan Perimeter. It was a 140-mile line that was the literal last stand. If that line snapped, the war was over. General Walton Walker famously told his troops there was "no more retreating."

The geography here was a double-edged sword. The rugged mountains made it hard for the NKPA to coordinate large-scale attacks, but the UN forces were pinned against the Sea of Japan and the Korea Strait. Logistics were a nightmare. Every bullet, every C-ration, and every drop of fuel had to come through the port of Pusan. It's one of the few times in modern warfare where a map shows a major power essentially pushed into a corner with nowhere left to run.

The Inchon Masterstroke and the Race North

Then everything flipped. General Douglas MacArthur pulled off what many thought was a suicidal gamble: the Inchon landing.

If you check out a topographic map of the Inchon area, you’ll see why it was a nightmare. The tides there are some of the most extreme in the world, fluctuating up to 30 feet. There are narrow channels and massive mudflats.

But MacArthur saw a shortcut. By landing at Inchon, near Seoul, he cut the North Korean supply lines right in the middle. Suddenly, the maps of the Korean War changed overnight. The NKPA forces around Pusan were suddenly the ones in danger of being cut off.

The momentum shifted so fast it’s hard to track. UN forces didn't just retake Seoul; they surged past the 38th Parallel. By October 1950, the maps showed UN troops reaching the Yalu River—the border with China.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

This is where the maps get deceptive. On paper, it looked like total victory. In reality, the UN forces were overextended. They were spread thin across frozen, jagged mountains where the roads were barely more than goat paths. General Ned Almond’s X Corps and the 8th Army were separated by the Taebaek Mountains, a gap in the map that the Chinese People's Volunteer Army (PVA) was about to exploit.

The Frozen Map: Chosin Reservoir

November 1950. The map changes again, but this time it's not about lines moving; it's about survival.

When China entered the war, they didn't use tanks or heavy trucks that showed up on aerial reconnaissance. They moved at night, on foot, through the mountains. The map of the Chosin Reservoir campaign is a chilling visual of encirclement. You have the 1st Marine Division stretched out along a single, treacherous mountain road.

The "Frozen Chosin" is a testament to how terrain dictates battle. The Chinese held the high ground on both sides of the road. On a map, the UN positions looked like a long, thin string being snipped into pieces. The subsequent retreat to the port of Hungnam is one of the greatest sealifts in history.

The Meatgrinder and the 38th Parallel

After the Chinese intervention pushed the UN back south—even losing Seoul again—the war entered its most grueling phase. By mid-1951, the massive swings across the map stopped.

The maps of the Korean War from 1951 to 1953 are frustratingly static. This was the "War of the Hills." Names like Pork Chop Hill, Heartbreak Ridge, and Old Baldy became famous. If you look at a tactical map of these areas, it looks like World War I. Trenches, bunkers, and barbed wire.

The 38th Parallel wasn't a wall. It was a concept. The actual fighting happened along the "Main Line of Resistance" (MLR). This line moved by inches and yards, not miles. Thousands of men died for a single ridge that might move the map border by a few hundred meters.

Why? Because both sides were negotiating in Panmunjom. The map at the time of the ceasefire would become the new border. Every hill mattered because it provided "line of sight." If you held the hill, you controlled the valley below.

Decoding the Cartography: What Most People Get Wrong

People often think the 38th Parallel and the DMZ are the same thing. They aren't.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

- The 38th Parallel is a circle of latitude. It’s a straight line on a map. It was chosen somewhat arbitrarily by two American colonels (Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel) in August 1945 using a National Geographic map. They just needed a quick way to divide Soviet and American zones.

- The Military Demarcation Line (MDL), which sits inside the DMZ, is a jagged line. It follows the actual positions of the troops when the shooting stopped in 1953.

If you look at a side-by-side map, you'll see the DMZ actually gives South Korea a bit more territory on the eastern side (which is mountainous and defensible) while North Korea gained a bit on the western side.

Why the Mountains Mattered More than the Cities

In European war maps, you follow the roads and the cities. In Korea, you follow the ridges.

The Korean Peninsula is about 70% mountains. This meant that armor—the tanks that dominated WWII—was often restricted to narrow valleys. If you look at a map of North Korean tank movements in 1950, they are stuck to the corridors. Once the UN forces established "blocking positions" at the ends of these valleys, the tanks became sitting ducks.

This forced the war into a light-infantry struggle. It’s why the maps show so many "pockets" and "envelopments." It wasn't about sweeping across a plain; it was about climbing a 3,000-foot peak, carrying a mortar on your back, and trying to stay warm while the enemy tried to flank you through a ravine the map didn't even show properly.

Real Sources and Geographical Evidence

To really understand these maps, you have to look at the work of the Army Map Service (AMS). During the war, they were frantically trying to update maps that were often based on old Japanese surveys from the colonial era.

Military historians like Allan R. Millett have pointed out that the lack of accurate topographical data in 1950 led to several "lost" battalions. Units thought they were on one ridge when they were actually on another, separated by an impassable gorge.

The most accurate visual record we have today comes from the Korean War Project and the National Archives (NARA). These archives hold the original "After Action Report" maps. They are messy, hand-drawn with grease pencils, and often stained with sweat or rain. They show the reality: war isn't a clean line on a screen; it's a series of panicked circles and arrows in the mud.

The Modern Legacy of These Maps

Today, the maps of the Korean War serve as the blueprint for the most heavily fortified border on Earth.

The DMZ is 2.5 miles wide and 155 miles long. When you look at satellite imagery now, the map shows a strange green ribbon. Because humans haven't been allowed in that strip for over 70 years, it’s become an accidental nature preserve. Rare cranes and even tigers are rumored to live in a space defined by a map drawn during a ceasefire.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

But there's a tension there.

South Korean maps often show the entire peninsula as one country, with provinces in the North still having appointed "governors" who can't actually go there. North Korean maps do the same. The maps are a political statement of intent. They represent a "frozen" conflict where the lines drawn in 1953 were never meant to be permanent, yet they have become some of the most enduring borders in modern history.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're looking to dive deeper into the cartography of this conflict, don't just look at a general overview. You need to get specific.

1. Use the West Point Atlas

The United States Military Academy has a digital collection of Korean War maps that are the gold standard. They show movement in "phases," which helps you see the accordion effect I mentioned earlier. You can see the flow of the front lines from June 1950 to July 1953 in clear, chronological steps.

2. Look for "Situation Maps"

Standard history books give you the "big picture." If you want the truth, search for "SITMAPS." These were produced daily (sometimes twice daily) at the divisional level. They show where individual regiments were. This is where you see the "holes" in the line that led to disasters like the Kunu-ri Gauntlet.

3. Overlay Topography with Battle Lines

If you use a tool like Google Earth and overlay a map of the Battle of the Punchbowl, you'll see why it was so hard to take. The "Punchbowl" is a literal bowl-shaped valley surrounded by high peaks. Seeing the 3D terrain explains why the casualty rates were so high much better than a 2D map ever could.

4. Check the "Iron Triangle"

Look at the area between Cheorwon, Kumhwa, and Pyonggang. This was a vital transportation hub in the center of the peninsula. If you control that triangle on the map, you control the ability to move troops between the east and west coasts. This explains why the fighting there in 1952 was so relentless.

The maps tell us that while the war is often called "The Forgotten War," its scars are still visible in the earth. The lines drawn in 1953 didn't just end a battle; they created a geopolitical reality that we are still dealing with every single day. Understanding the map is the only way to understand why the peace is so fragile.

Next time you see a map of Korea, don't look at the border. Look at the mountains. That's where the real story is.