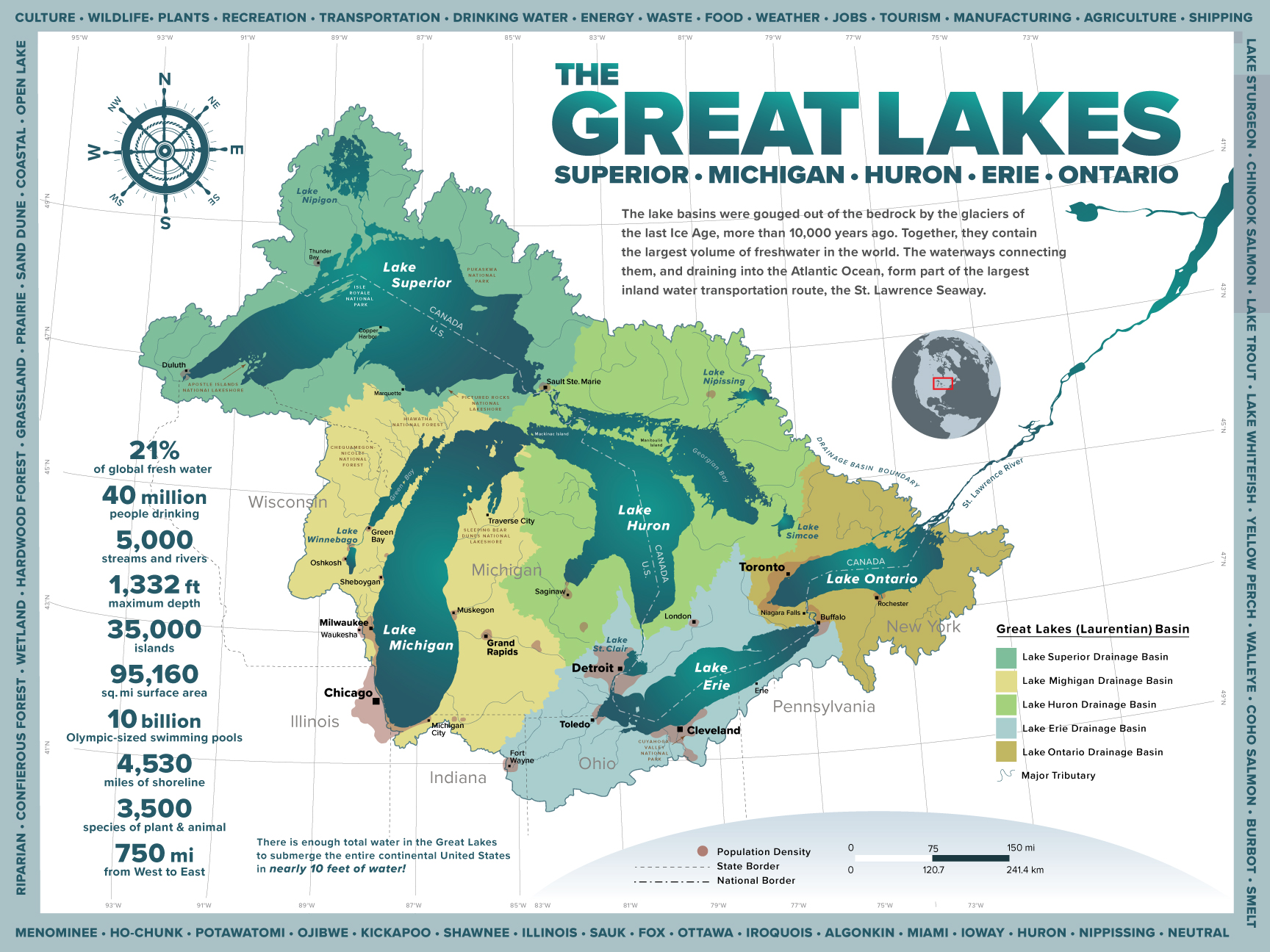

You look at a map of North America and those five blue fingers in the middle seem permanent. Solid. They're basically the anchors of the continent, right? Well, honestly, maps of the Great Lakes are way more of a "work in progress" than your middle school geography teacher probably let on.

If you grab a bathymetric map from the 1950s and compare it to a high-resolution NOAA digital elevation model from today, the differences aren't just about better pixels. The land is actually moving. It's called post-glacial rebound. Basically, the earth is still springing back up like a heavy mattress after the glaciers melted 10,000 years ago. This means the northern shores are rising faster than the southern ones, which literally tilts the lake basins.

When you're looking at maps of the Great Lakes, you aren't just looking at water; you’re looking at a shifting geological puzzle that affects everything from multi-billion dollar shipping lanes to where someone can legally build a summer cottage.

The Secret History of Mapping the Inland Seas

Early European cartography of this region was, frankly, a mess. Samuel de Champlain and other explorers were mostly guessing. They’d hear stories from Indigenous guides about "vast waters" and just sort of sketch a giant blob where Michigan should be. It wasn't until the 1800s that the U.S. Lake Survey—established by Congress in 1841—actually started taking the job seriously.

They used lead lines. Think about that for a second. To map the bottom of Lake Superior, which drops down over 1,300 feet, guys were literally dropping heavy weights on ropes over the side of wooden boats. It took decades. Thousands of soundings.

Today, we use multibeam sonar and LIDAR. It’s wild. We can see shipwrecks in crisp detail without ever getting wet. But those old paper maps? They’re still the foundation of how we understand the "bones" of the lakes.

Why Depths Matter More Than Outlines

Most people look for the coastline. Sailors look for the "blue."

🔗 Read more: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

Navigation charts are a specific breed of maps of the Great Lakes. They don't care about the trees or the cities; they care about the shoals that will rip the bottom out of a 1,000-foot freighter. Take the "Graveyard of the Great Lakes" near Whitefish Point. The maps there are littered with symbols for wrecks.

The depth isn't static, either. The "Low Water Datum" is the reference point cartographers use, but the actual water levels swing wildly based on precipitation and evaporation. In 2013, levels were at record lows. By 2020, they were hitting record highs. If you’re using an outdated map to navigate a rocky channel in the Georgian Bay, you’re basically asking for a very expensive insurance claim.

The Mystery of the Sixth Great Lake (On Old Maps)

Check out a map from the late 1700s. You might see "Lake Michigan" and "Lake Huron," but sometimes you’ll see islands that don't exist. The "Isles of Philippeaux" and "Pontchartrain" appeared on the Mitchell Map of 1755.

They were fakes.

Basically, a savvy explorer named Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix named them after his patrons to secure more funding. These phantom islands stayed on official maps for nearly a century because nobody bothered to go out there and check. They were even mentioned in the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War. Imagine defining a national border based on islands that were literally made up for a paycheck.

How to Read a Modern Great Lakes Map

You've got three main types of maps today.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

First, there’s the Topographic/Bathymetric map. These are the ones that show the "invisible" mountains underwater. If you want to find where the lake trout are hiding, you look for the steep drop-offs and "holes" like the Caribou Basin in Superior.

Second, there are Current and Thermal maps. These look like psychedelic weather reports. NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL) puts these out. They show how the water moves. Did you know Lake Michigan has a massive counter-clockwise swirl? Or that the water in Lake Superior takes nearly 200 years to fully "flush" out? These maps prove the lakes aren't just big ponds; they’re internal oceans with their own tides and weather systems.

Third, the Aeronautical and Nautical charts. These are the "utility" maps. They’re cluttered with lights, buoys, and magnetic anomalies. Some spots in Lake Superior have so much iron ore in the rocks that they actually make a traditional compass spin in circles. You won't find that on a Google Map, but it’s vital information if your GPS dies.

The Border That Isn't There

One of the weirdest things about maps of the Great Lakes is the international border. It’s an invisible line that zig-zags through the middle of four of the five lakes (Lake Michigan is entirely within the U.S.).

On paper, it’s a sharp line. In reality? It’s a nightmare for fishermen. You can be trolling for walleye and cross into Canadian waters without knowing it. That’s why modern digital maps for fishfinders have "boundary alerts." It's a weird tension between the physical reality of the water and the political reality of the map.

Environmental Mapping: The New Frontier

Lately, the maps are getting "greener." We’re seeing more "Benthic Habitat Maps."

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

What does that mean? It means we’re mapping the stuff living on the bottom. Why? Invasive species. The Quagga mussel has basically carpeted the bottom of Lake Michigan. They’ve changed the water clarity so much that NASA can see deeper into the lakes from space than ever before.

We also use maps to track "toxic plumes" or "dead zones," especially in the shallow Western Basin of Lake Erie. These maps are tools for survival. They tell us when the water is safe to drink and where the toxic algae blooms are heading.

Finding the Best Maps for Your Needs

If you’re just a fan of the aesthetics, look for vintage reproductions of the 1800s Lake Survey charts. The typography is beautiful, and they look great on a wall.

For the hikers and explorers, look for USGS 7.5-minute quadrangles. These give you the "real" detail of the shoreline—the dunes, the bluffs, and the hidden creek mouths that don't show up on a phone screen.

For the data nerds, the Great Lakes Observing System (GLOS) is the gold standard. It’s a live-data map. You can click on a buoy in the middle of Lake Huron and see exactly how high the waves are right now. It's the ultimate fusion of cartography and real-time tech.

Actionable Insights for Great Lakes Mapping

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Great Lakes cartography, skip the generic gas station maps and follow these steps for a more authentic experience:

- Download the NOAA BookletCharts: These are free, high-resolution PDF versions of official nautical charts. They are scaled for printing on home printers and provide incredible detail for boaters or history buffs.

- Use the GLOS Seagull Platform: This is a modern interface for real-time lake conditions. It’s the most advanced way to "map" what is happening on the water in terms of temperature, wind, and wave height.

- Check the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI): They host the "Great Lakes Bathymetry" datasets. If you have any GIS (Geographic Information System) skills, you can download the raw data and create your own custom 3D models of the lake floors.

- Look for "LIDAR Shoreline" imagery: If you are interested in coastal erosion, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regularly maps the shoreline with lasers to see how much of the beach is disappearing each year. It's a fascinating, if slightly depressing, look at the power of the water.

The Great Lakes are too big to see all at once, which is why we’ve spent 400 years trying to draw them. Whether it’s for a fishing trip or just to understand the scale of the world’s largest freshwater system, the right map changes how you see the "Third Coast."