You’re sitting in your living room, maybe scrolling through your phone, and suddenly there’s a pounding at the door. It’s the police. They say they’re looking for someone—a suspect in a bombing. You ask for a warrant. They don’t have one. You tell them to kick rocks.

Most of us take it for granted that the "blue wall" stops at our doorstep unless a judge signed a piece of paper. But for a long time in American history, that wasn't actually the reality at the state level. If a local cop broke down your door and found something illegal, they could usually use it to throw you in prison, even if they broke the law to get it.

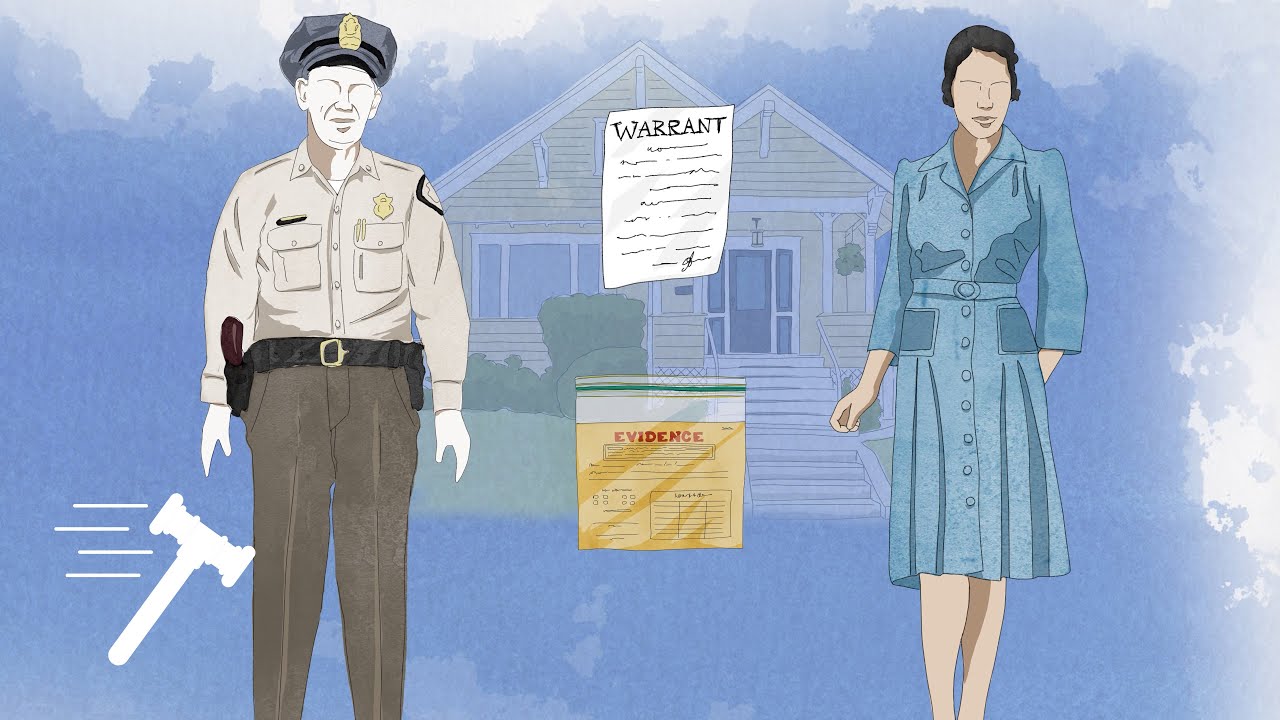

That changed because of a woman named Dollree Mapp. The Mapp v. Ohio summary isn't just a dry legal brief; it’s a gritty story about a bombing, a fake warrant, and a trunk full of "obscene" books in a Cleveland basement.

The Day the Cops Flubbed the Fourth Amendment

On May 23, 1957, Cleveland police got a tip. They heard a guy named Virgil Ogletree was hiding out in Dollree Mapp's house. Ogletree was a suspect in a bombing involving the future boxing promoter Don King. They also thought there might be some illegal gambling slips—"policy paraphernalia"—stashed there.

Mapp wasn't having it. She called her lawyer, who told her: "Don't let them in without a warrant."

She didn't.

The police waited. They watched the house. Three hours later, more officers showed up and basically laid siege to the place. When Mapp wouldn't open the door, they broke a window, reached in, and let themselves in.

🔗 Read more: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

Here's where it gets weirdly theatrical. Mapp demanded to see the warrant. One of the officers, Sergeant Carl Delau, held up a random piece of paper. Mapp, being no wallflower, grabbed the paper and shoved it down her shirt to keep it as evidence. The cops struggled with her, recovered the "warrant" (which was never seen again and definitely wasn't real), and handcuffed her for being "belligerent."

They tore the house apart. They didn't find the bomber in her apartment—though they found him in the downstairs unit. They didn't find the gambling slips. What they did find, in a trunk in the basement, were some "lewd and lascivious" books and photos.

Under Ohio law at the time, possessing that stuff was a crime. Mapp was convicted. She was sentenced to one to seven years in the Ohio Reformatory for Women.

Why the Supreme Court Cared (It Wasn't About the Books)

When the case reached the Supreme Court in 1961, Mapp’s lawyers were actually focused on the First Amendment. They were arguing that the Ohio obscenity law was way too broad.

But the Court had a different itch to scratch.

Since 1914, there had been a rule called the Exclusionary Rule. It came from a case called Weeks v. United States. Basically, it said if federal agents find evidence through an illegal search, they can't use it in court. It’s the "fruit of the poisonous tree" logic. If the source is tainted, the evidence is out.

💡 You might also like: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

The problem? That rule only applied to the feds.

If you were a local or state cop, you could basically ignore the Fourth Amendment’s ban on "unreasonable searches and seizures." You might get sued, or your boss might yell at you, but the evidence stayed in. In a 1949 case called Wolf v. Colorado, the Court had basically said, "Yeah, the states should follow the Fourth Amendment, but we aren't going to force them to throw out illegal evidence."

By 1961, the Warren Court was tired of that double standard. Justice Tom C. Clark, writing for the majority, basically said that without the Exclusionary Rule, the Fourth Amendment was a "form of words"—it had no teeth.

The Fallout: "The Criminal Is to Go Free Because the Constable Has Blundered"

Not everyone was happy. Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote a stinging dissent. He thought the Court was overreaching and that states should be allowed to figure out their own ways to police the police.

Critics of the Mapp v. Ohio summary and its legacy often quote Judge Benjamin Cardozo, who famously complained that under this rule, "The criminal is to go free because the constable has blundered."

It’s a fair point to debate. Does it make sense to let a murderer go because a cop forgot to get a signature? But the majority in Mapp argued that if the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for the law.

📖 Related: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

What Most People Get Wrong About Mapp

Honestly, a lot of people think Mapp means any mistake by police gets a case tossed. It's not that simple anymore. Over the last 60 years, the Court has chipped away at this:

- Good Faith Exception: If the cops thought they had a valid warrant (but the judge made a clerical error), the evidence usually stays in.

- Inevitable Discovery: If the police can prove they would have found the stuff anyway through legal means, it’s not excluded.

- Independent Source: If they find the evidence again later using a totally separate, legal lead, it counts.

How This Hits Your Life Today

If you’re ever in a situation where you feel your privacy has been invaded, the Mapp decision is your primary shield. It forced every police department in America to professionalize. It’s the reason why "Search and Seizure" is a massive part of every police academy's curriculum.

Without Dollree Mapp's defiance, your Fourth Amendment rights would essentially be a suggestion rather than a requirement at the local level.

What to do if you think your rights were violated:

- Don't Resist Physically: Dollree got handcuffed for being "belligerent." Let the lawyers handle the fight in court.

- Ask "Am I Free to Go?": If the answer is yes, walk away.

- Explicitly State "I Do Not Consent to a Search": Even if they do it anyway, you need this on the record for your lawyer to use the Mapp precedent later.

- Document Everything: Write down badge numbers and the exact timeline of when they entered.

You’ve got to remember that the Exclusionary Rule isn’t about protecting "criminals"; it’s about protecting the sanctity of everyone's home. If the police can enter Dollree Mapp’s house without a warrant, they can enter yours too.

To dig deeper into how your privacy is protected in the digital age, you should look into how the Fourth Amendment applies to your cell phone data—a modern battleground that started with a trunk of books in a 1950s basement. Check out the 2014 case Riley v. California to see the next chapter of this story.