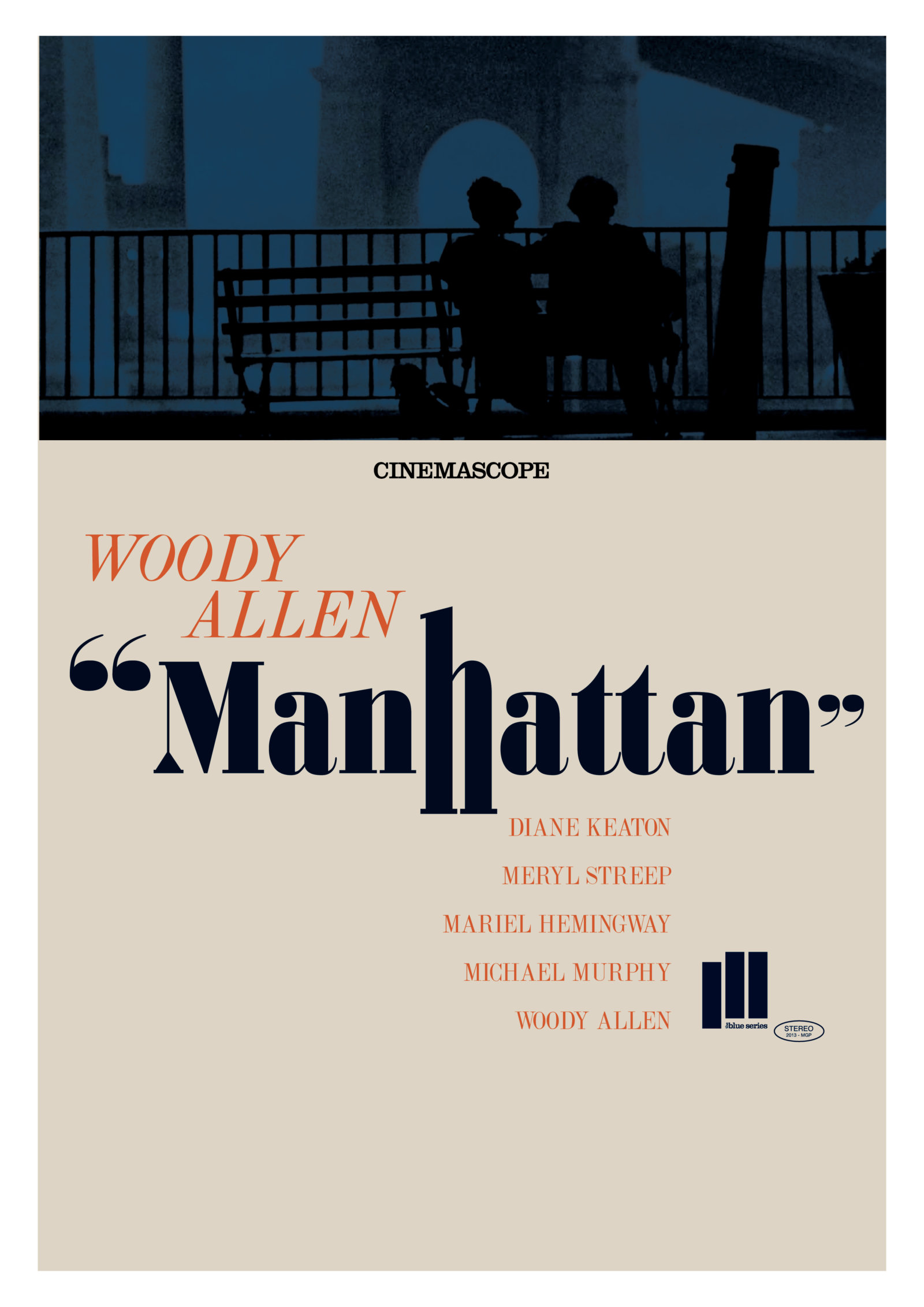

It starts with the drums. That Gershwin swell. Then, the black-and-white skyline of a New York that probably never actually existed outside of a viewfinder. When people talk about the Manhattan movie Woody Allen released in 1979, they usually start with the visuals. Gordon Willis, the cinematographer who also shot The Godfather, turned the Upper East Side into a charcoal-and-silver dreamscape. It looks expensive. It looks intellectual. It looks like a place where everyone has a therapist and a subscription to The New York Review of Books.

But honestly? The movie is a mess of contradictions. It’s a masterpiece that some people now find completely unwatchable. It’s a love letter to a city that simultaneously mocks the people living in it.

The Plot We Tend to Forget

Isaac Davis is 42. He’s quit his job writing for a TV show he hates. He’s miserable. But the kicker, the thing that drives the entire narrative engine of the Manhattan movie Woody Allen created, is Tracy. She’s 17. Mariel Hemingway plays her with this heartbreakingly sincere innocence that makes Isaac’s neurotic rambling feel even more predatory than it already is.

💡 You might also like: Mickey Mouse and Daisy Duck: The Surprising Truth About Their Disney Dynamic

He’s dating a high schooler. He knows it’s weird. He tells her she’s a "godsend," but he also treats her like a temporary placeholder until a "grown-up" woman comes along. That woman is Mary Wilkie, played by Diane Keaton. Mary is high-strung, pseudo-intellectual, and currently having an affair with Isaac’s best friend, Yale.

The movie isn't really about a plot. It's about a vibe. It’s about people sitting in Zabar's or the Guggenheim and trying to talk their way out of being lonely. They use big words to hide small feelings. It's funny. It's also deeply cringey.

The 17-Year-Old Elephant in the Room

We have to talk about Tracy.

In 1979, critics mostly gave it a pass. They called it "sophisticated." Today? It’s the primary reason the film sits in a weird cultural purgatory. Knowing what we know now about Allen’s personal life—the allegations, the marriage to Soon-Yi Previn—watching Isaac Davis tell Tracy she’s too young for him while simultaneously kissing her in a carriage in Central Park feels... heavy.

There is no escaping the autobiography here.

Mariel Hemingway was actually 16 when they filmed. She has since spoken out in her memoir, Out Came the Sun, about how Allen allegedly flew to her family’s home in Idaho and suggested a trip to Paris. She stayed in her room. She didn't go.

When you watch the movie now, you aren't just watching a fictional character. You’re watching a blueprint. Isaac keeps telling Tracy to go to London, to grow up, to leave him. He wants to be the "moral" one by pushing her away, yet he’s the one who invited her into his bed in the first place. It’s a brilliant performance of a man performing morality while practicing the opposite.

Gordon Willis and the "Look" of 1970s New York

Forget the plot for a second. Look at the frame.

The Manhattan movie Woody Allen made is arguably the best-looking film of the 1970s. This wasn't an accident. Willis used Panavision cameras and anamorphic lenses to capture the horizontal sprawl of the city. He famously hated "TV lighting." He wanted shadows. He wanted deep blacks.

There’s a scene at the Hayden Planetarium. Isaac and Mary are walking through the exhibits. They are silhouettes against the glowing orbs of planets and stars. You can’t see their faces. You only hear their voices. It’s one of the most romantic sequences in cinema history, which is ironic because they are both being incredibly pretentious and dishonest in that moment.

That’s the magic trick of this film. It uses the most beautiful aesthetics imaginable to house some of the most unattractive human behaviors.

- The opening montage took weeks to edit.

- The bridge shot (Queensboro Bridge) involved a bench the crew brought themselves because the "real" ones didn't face the right way.

- The film was shot in 2.35:1 aspect ratio, which was rare for a comedy-drama.

Why the Gershwin Soundtrack Matters

"Rhapsody in Blue" is the heartbeat of the film. Allen originally wanted a more contemporary score, but he pivoted to George Gershwin to lean into the nostalgia.

It makes the movie feel like a memory. It’s not "New York in 1979." It’s "New York as Isaac Davis wants to remember it." The music swells during the fireworks, masking the sounds of the dirty, grimy city below. It provides a layer of class to a story that is essentially about people cheating on each other and lying to themselves.

The Script: Why It Still Bites

The dialogue is fast. It’s jagged.

"I think people should mate for life, like pigeons or Catholics."

It’s easy to see why people fell in love with this writing. It’s snappy. It feels like the way you wish you could talk at a party. But if you listen closely, no one is actually listening to anyone else. Mary dismisses entire artistic movements as "overrated." Isaac complains about his ex-wife (played by Meryl Streep) writing a tell-all book about their marriage.

Ironically, the Streep character, Jill, is the only one who seems to have her life together. She’s moved on. She’s happy. She’s honest. In the world of Isaac Davis, that makes her the villain.

Isaac is obsessed with "integrity." He quits his job because he doesn't want to write "garbage." Yet, he has zero emotional integrity. He dumps Tracy the second Mary becomes available, then tries to crawl back to Tracy the second Mary dumps him. He’s a child in a corduroy blazer.

Impact on Modern Filmmaking

You can see the DNA of this movie everywhere.

Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha. Greta Gerwig’s early work. Every "mumblecore" movie where people in Brooklyn sit around and talk about their feelings for 90 minutes. They all owe a debt to the Manhattan movie Woody Allen put out.

He pioneered the idea that you could make a "big" movie about "small" things. You didn't need a ticking bomb or a car chase. You just needed a bench, a bridge, and two people who are remarkably bad at being alone.

But there’s a darker legacy too. The film is often cited in discussions about "The Male Gaze" and the way Hollywood has historically fetishized the "man-child" who is "saved" by the purity of a younger woman. Tracy is the only character in the movie with actual wisdom. When she tells Isaac, "You have to have a little faith in people," it’s supposed to be the emotional climax.

In 1979, that was seen as a beautiful lesson. In 2026, it looks like a middle-aged man putting the burden of his emotional growth on a child.

Fact-Checking the Production

There are a few myths about the movie that always pop up in film school circles.

- Woody Allen hated it. This is true. He reportedly offered to direct a movie for United Artists for free if they promised not to release Manhattan. He thought it was too indulgent.

- The black and white was a gimmick. False. It was a choice to make the city look "timeless." Willis and Allen wanted it to look like the old photographs they grew up with.

- The ending was improvised. Not quite. The final look Tracy gives Isaac was meticulously timed. It’s arguably the most famous "final frame" in 70s cinema.

How to Watch It Today

If you’re going to sit down and watch it now, you have to do it with a dual lens.

You have to be able to appreciate the technical mastery. The way the light hits the pavement after a rainstorm. The way the dialogue overlaps like a jazz session. It is, undeniably, a work of high art.

But you also have to acknowledge the discomfort. You can't just ignore the age gap or the way the female characters are often filtered through Isaac’s neuroses. Being an "expert" viewer in 2026 means holding both of those truths at the same time.

Actionable Insights for Cinephiles

- Compare it to Annie Hall: Watch them back-to-back. Annie Hall is about the end of a relationship; Manhattan is about the inability to start one. Note the difference in how the city is filmed. Annie Hall is warmer; Manhattan is colder, more distant.

- Study the Silhouette: If you’re a photographer or filmmaker, look at the Planetarium scene. Notice how much information is conveyed without seeing a single facial expression.

- Read the Memoir: To get the full picture, read Mariel Hemingway’s Out Came the Sun. It provides the context that the screen skips over.

- Listen to the Gershwin: Don't just watch. Listen. The score is doing 50% of the emotional heavy lifting. Without that music, Isaac Davis is just a jerk in a suit. With it, he’s a "tragic figure."

The Manhattan movie Woody Allen gave the world is a fossil of a specific time in New York history. It’s beautiful, it’s problematic, it’s funny, and it’s deeply lonely. Whether you love it or hate it, you can't really understand American independent cinema without reckoning with it.

Just don't expect to feel good when the credits roll. You'll probably just feel like taking a long walk and wondering why we all make things so complicated.

Next, check out the restoration of Stardust Memories if you want to see where this "meta-narrative" style went next. Or better yet, go watch a movie by a filmmaker who actually likes the people they're filming.