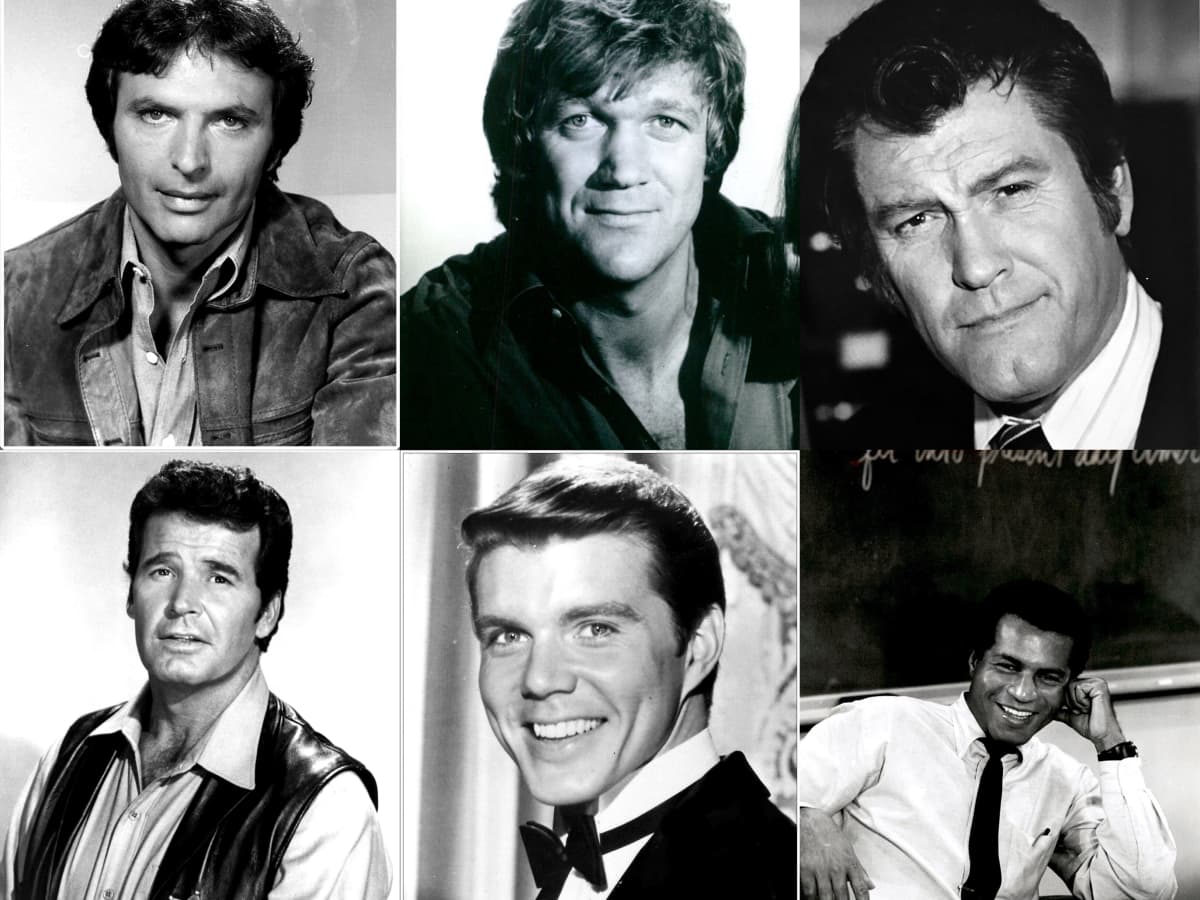

Walk into any acting class in Los Angeles or London right now. You’ll hear names like Chalamet, Elordi, or Butler. But if you watch those guys closely—the way they hold a cigarette in a scene, the way they lean against a doorframe, or that specific brand of "quiet" they project—you aren't seeing something new. You’re seeing the DNA of male actors of the 60s. It was the decade where the "Leading Man" archetype basically broke in half. Before 1960, you had the stiff upper lip of the studio system. Afterward? You had grit. You had sweat. You had guys who looked like they actually worked for a living.

The 1960s weren't just about the counterculture or the Beatles; they were about a fundamental shift in how men were allowed to exist on screen. Honestly, it was the first time "cool" became a measurable currency in cinema.

The Death of the Suit and the Rise of the Anti-Hero

For decades, if you were a male lead, you wore a suit. You spoke clearly. You were Clark Gable or Cary Grant. Then the 60s hit and suddenly, the biggest stars in the world were mumbling. Or they were covered in dirt. Or they were playing characters who were, frankly, kind of jerks.

Take Steve McQueen. People call him the "King of Cool," and it’s almost a cliché at this point. But watch Bullitt (1968) again. He barely talks. Like, seriously, he has maybe a few pages of dialogue in the whole film. He realized that the camera captures thought, not just speech. That was a revolutionary concept for male actors of the 60s. They stopped performing for the back row of the theater and started living for the lens. McQueen didn't need a monologue to tell you he was frustrated; he just shifted gears in that Mustang.

Then you have the "Brando Effect." While Marlon Brando peaked in the 50s with On the Waterfront, his influence in the 60s created a vacuum that guys like Paul Newman filled. Newman is a weird case study because he was devastatingly handsome—the kind of face the old studios would have used for generic romances—but he had this internal rebellion. In Hud (1963), he plays a man who is genuinely unredeemable. No "heart of gold" moment. Just a cold, selfish guy. Audiences loved it. It was the birth of the protagonist you didn't necessarily want to grab a beer with, but you couldn't look away from.

💡 You might also like: Anne Hathaway in The Dark Knight Rises: What Most People Get Wrong

The British Invasion (But for Movies)

While Hollywood was getting gritty, the UK was exporting a very different kind of masculinity. It wasn't just James Bond, though Sean Connery obviously redefined the global standard for "rugged suave."

- Michael Caine: He brought the working-class Cockney accent to the forefront. Before Alfie (1966) or The Italian Job (1969), leading men in Britain were expected to sound like they went to Oxford. Caine basically told the establishment to shove it.

- Richard Harris and Richard Burton: These were the "hellraisers." They brought a theatrical, booze-soaked intensity to the screen that felt dangerous.

- Peter O'Toole: Lawrence of Arabia (1962). That’s it. That’s the tweet. He showed that a male lead could be ethereal, vulnerable, and almost feminine in his beauty while still carrying an epic four-hour war movie on his back.

Sidney Poitier and the Weight of the World

You can't talk about male actors of the 60s without talking about the sheer bravery of Sidney Poitier. While other actors were choosing between playing a cowboy or a spy, Poitier was literally carrying the moral conscience of a segregated America on his shoulders.

In 1967 alone, he released To Sir, with Love, In the Heat of the Night, and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner. Think about that. That's a legendary career's worth of impact in twelve months. In In the Heat of the Night, when he slaps a wealthy white plantation owner back after being slapped himself—the "slap heard round the world"—it wasn't just a scripted moment. It was a cultural earthquake. Poitier had a clause in his contract that he wouldn't be struck without striking back. That is power. That is how you change an industry.

The Method Men and the New York Shift

By the late 60s, the "Studio System" was basically a corpse. The kids had taken over the playground. This gave rise to the New York-trained actors who cared more about "The Method" than their lighting.

📖 Related: America's Got Talent Transformation: Why the Show Looks So Different in 2026

Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate (1967) changed everything. He wasn't tall. He wasn't conventionally "hunky." He was awkward. He was nervous. He looked like a regular guy who had no idea what he was doing with his life. That resonated with the youth more than any John Wayne movie ever could.

Then came the 1969 explosion of Midnight Cowboy. Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman playing a gigolo and a con man in a decaying New York City. It was the first (and only) X-rated movie to win Best Picture. It showed that male actors could explore friendship, failure, and desperation without needing a heroic payoff.

Why the "Cool" of the 60s Was Actually Hard Work

People think these guys were just born with that effortless vibe. They weren't. It was a craft.

Lee Marvin is a great example. If you see him in The Dirty Dozen (1967) or Point Blank (1967), he moves with this predatory stillness. Marvin was a decorated Marine in WWII, and he brought that genuine lethality to the screen. He didn't have to "act" tough; he just was. This authenticity is something modern CGI-heavy movies often lack. You can't fake the mileage on a face like Lee Marvin’s or Charles Bronson’s.

👉 See also: All I Watch for Christmas: What You’re Missing About the TBS Holiday Tradition

The Actors Who Bridged the Gap

- Robert Redford: He started the decade in TV and ended it as the biggest star on the planet with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). He was the bridge between the old-school golden boy and the new-school rebel.

- Clint Eastwood: He went to Italy because Hollywood didn't know what to do with him. He filmed the "Dollars Trilogy" with Sergio Leone and brought back a style of "Man with No Name" minimalism that still defines the Western genre today.

- Warren Beatty: He wasn't just an actor; he was a producer who understood that the "New Hollywood" needed to be provocative. Bonnie and Clyde (1967) changed how violence was depicted forever.

What We Get Wrong About 1960s Stardom

We tend to look back through a nostalgic filter and think everyone was a legend. Honestly? There was a lot of junk too. For every Cool Hand Luke, there were ten forgettable beach party movies. But the reason the male actors of the 60s endure is that they were the first generation to be "real" on camera. They allowed themselves to be ugly, sweating, and wrong.

They also worked within a system that was dying, which gave them a unique kind of desperation. They were trying to prove that movies still mattered in the age of television.

How to Apply the 60s Method to Modern Viewing (or Acting)

If you're a film buff or someone looking to understand why certain performances "work" today, look for these three things that the 60s greats mastered:

- Economy of Motion: Watch Paul Newman. He never does three gestures when one will do. Modern acting is often too "busy."

- The Power of the Silence: Notice how often Steve McQueen or Clint Eastwood lets the other person talk while they just observe. The power in a scene usually belongs to the person listening, not the person talking.

- Physicality over Dialogue: Before you watch a movie, ask if you could understand the character's motivation with the sound turned off. The best 60s leads could tell a whole story just by the way they walked down a street.

To truly appreciate this era, start with a "Triple Threat" watchlist: The Apartment (Jack Lemmon showing the Everyman side), The Manchurian Candidate (Frank Sinatra showing his underrated acting chops), and Hud (the peak of the anti-hero). You’ll see that these guys weren't just "stars"—they were architects of the modern masculine identity.

If you want to dive deeper into this, the next logical step is to look at the "New Hollywood" directors of the early 70s—Scorsese, Coppola, Spielberg—who took these 60s archetypes and pushed them even further into the edge of realism. The 60s laid the tracks; the 70s just drove the train off the cliff. Explore the transition from the polished 1960 leading man to the gritty 1969 rebel to see the most dramatic shift in cinematic history.