Walk through the doors of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and you'll eventually find yourself staring into the eyes of a woman who looks like she knows exactly what you’re thinking. She’s leaning back, one hand resting against her cheek, wearing a black dress that seems to swallow the light. This is Madeleine Brohan by Paul Baudry. Honestly, it’s one of those paintings that stops you mid-stride, even if you aren’t an art history nerd. There’s a specific kind of magnetism here. It isn't just about the brushwork or the way the silk looks—though Baudry was a master of that—it’s about the personality radiating off the canvas.

Most portraits from 1860 feel stiff. They feel like people posing for an Instagram photo where they’re trying way too hard to look "aesthetic." But Madeleine? She looks bored. Or maybe she’s just amused. She was a star of the Comédie-Française, a woman who lived her life in the spotlight, and Baudry captured her not as a performer, but as a person who was tired of the performance.

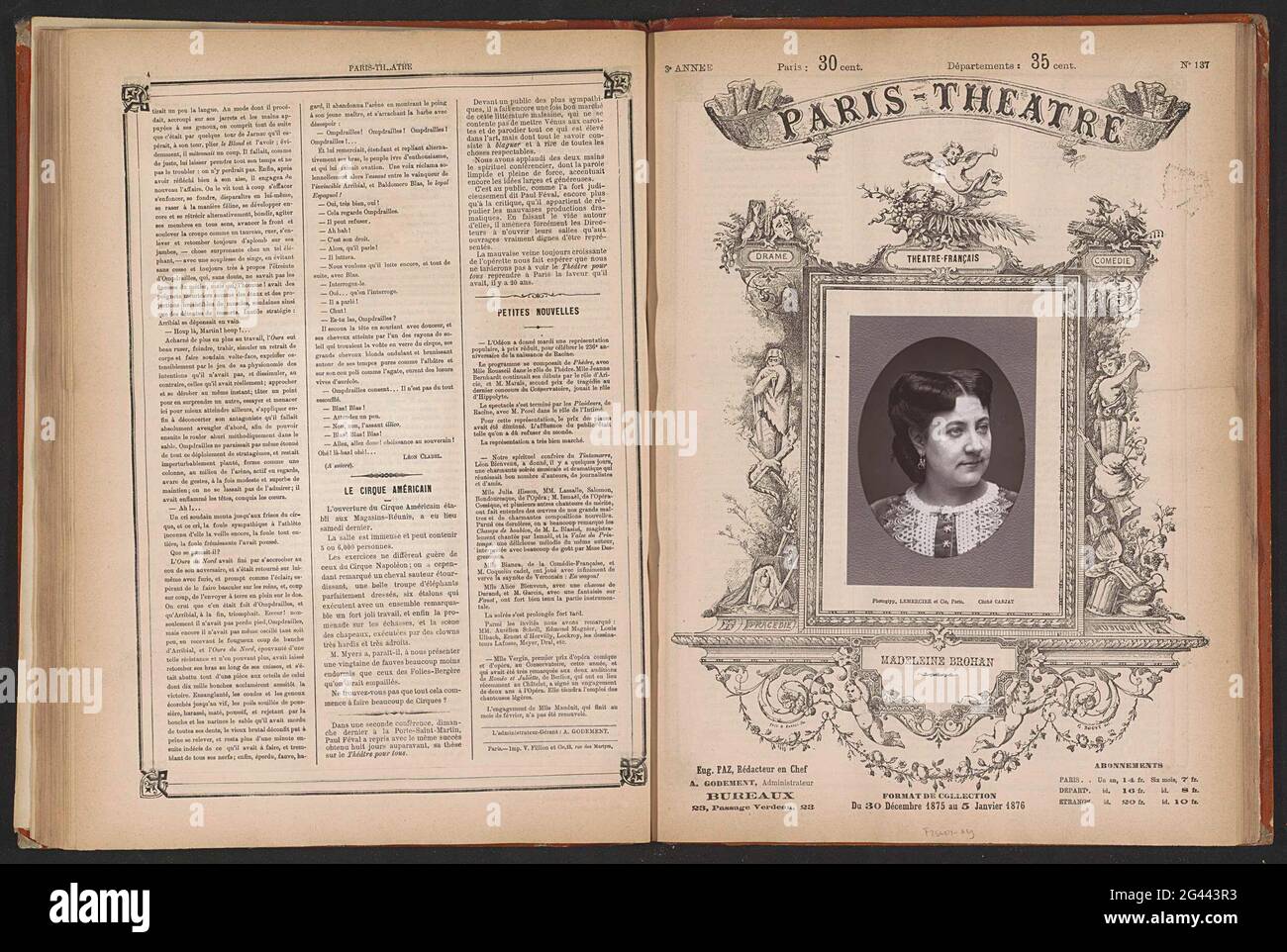

The Woman Behind the Silk: Who Was Madeleine Brohan?

To understand why this painting works, you have to know who Madeleine was. She wasn't just some random model Baudry found on the street. She was royalty in the theatrical world. Born into a family of actors, she debuted at the Comédie-Française at eighteen. People loved her. She had this "grande dame" energy that made her perfect for Molière plays.

But her life wasn't just applause and curtain calls. She had a messy marriage to Mario Uchard that ended in a very public, very scandalous separation. In the mid-19th century, that was a big deal. She was a woman who navigated a world run by men while maintaining a sharp wit and a bit of a "don't mess with me" attitude. When Paul Baudry sat down to paint her in 1860, he wasn't just painting a pretty face. He was painting a survivor of the Parisian social circuit.

Paul Baudry: More Than Just the Paris Opera Guy

Paul Baudry is mostly famous today for the ceiling of the Palais Garnier. You know, the big, epic, gold-leafed spectacles. But Madeleine Brohan by Paul Baudry shows a completely different side of his talent. It’s intimate. It’s quiet.

Baudry was a Prix de Rome winner, which basically meant he was the "golden boy" of the French academic style. He knew all the rules. He knew how to make skin look like pearls and how to drape fabric so it looked expensive. But in this portrait, he breaks the rules of formal portraiture just enough to make it feel modern.

Look at the composition. It’s tight. It’s focused. He uses a dark, almost murky background to push Madeleine forward. It’s a technique called chiaroscuro, but Baudry uses it to create psychological depth rather than just dramatic lighting. He was obsessed with the masters of the Renaissance, specifically Titian and Correggio, and you can see that influence in the softness of her skin. It’s fleshy and real.

📖 Related: Charlie Gunn Lynnville Indiana: What Really Happened at the Family Restaurant

The Dress That Defined an Era

Let’s talk about that dress. It’s black, which was the height of chic in Second Empire Paris, but it’s the texture that gets you. Baudry paints the sheen of the satin and the weight of the velvet in a way that makes you want to reach out and touch it. Don't do that, though—the Orsay security guards are very fast.

The choice of black serves a dual purpose. First, it makes her face and hands pop. Second, it signals her status. She isn't a young debutante in white lace; she’s a woman of substance. The way the lace collar frames her neck is delicate, almost fragile, which contrasts with the heavy darkness of the rest of the outfit. It’s a masterclass in visual balance.

Why This Painting Hits Differently Than Other Portraits

If you compare this to portraits by Franz Xaver Winterhalter—who was painting Empress Eugénie and the rest of the court at the time—Baudry’s work feels almost gritty in its honesty. Winterhalter made everyone look like a porcelain doll. Baudry made Madeleine look like she just finished a long conversation and is waiting for you to say something smart.

There’s a slight puffiness under her eyes. Her expression is a bit weary. This is what real beauty looks like after the party is over.

- The Pose: It’s casual. The hand-to-face gesture is something we do when we’re thinking or listening intently. It breaks the "official" vibe of 19th-century art.

- The Gaze: She isn't looking at us; she’s looking through us.

- The Color Palette: It’s incredibly restrained. Aside from the flesh tones and the small pop of gold in her jewelry, it’s a study in blacks and grays.

It’s actually kind of funny. Baudry was often criticized for being "too pretty" or "too decorative" in his bigger commissions. But here? He’s focused. He’s intense.

The Legacy of the 1860 Salon

When this painting was shown at the Salon, it was a hit. The Salon was basically the Oscars of the art world back then. If you did well there, you were set for life. Critics praised the "fineness" of the execution. But more than that, they recognized the spirit of the sitter.

👉 See also: Charcoal Gas Smoker Combo: Why Most Backyard Cooks Struggle to Choose

It’s important to remember that during this time, photography was starting to become a thing. Painters were feeling the pressure. Why pay a guy months of salary to paint you when a camera could do it in minutes? Madeleine Brohan by Paul Baudry is the answer to that question. A camera can capture what you look like. Baudry captured how it felt to be in the room with her.

That’s why we still talk about it. It’s why it has a permanent home in one of the greatest museums on earth. It’s a bridge between the old-school classical world and the psychological realism that would eventually lead to Impressionism.

Seeing It for Yourself: A Practical Tip

If you’re planning a trip to the Musée d’Orsay, don't just rush to the Van Goghs or the Monets. The Baudry portrait is usually located in the areas dedicated to the "Juste Milieu" or the academic masters of the mid-19th century.

Check the lighting. The way the gallery lights hit the surface of the oil reveals the layers of glaze Baudry used. It’s almost holographic. You can see the tiny strokes of white he used to create the "sparkle" in her eyes. It’s those little details that remind you this was painted by a human hand, not a machine.

How to Appreciate Academic Art in a Modern World

We live in a world of fast media. We scroll through thousands of images a day. Taking ten minutes to stand in front of Madeleine Brohan by Paul Baudry is a bit of a rebel act.

- Observe the "Lost Edges": Look at where her sleeve meets the background. It isn't a hard line. It blurs. That’s how our eyes actually see light.

- Study the Hands: Hands are notoriously hard to paint. Baudry makes them look effortless, soft, and expressive.

- Think About the Silence: There’s a specific quietness to this painting that’s hard to find in modern digital art.

Honestly, the painting is a vibe. It’s the 1860 version of "main character energy." Madeleine Brohan wasn't just a subject; she was a force, and Baudry had the sense to stay out of her way and just let her shine through the paint.

✨ Don't miss: Celtic Knot Engagement Ring Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Steps for Art Lovers

If you want to dive deeper into this specific style or this era of art, here is how you can actually engage with it beyond just reading an article.

First, look up the "Comédie-Française" archives. They have records of the roles Madeleine played. Seeing her in costume versus seeing her in Baudry’s portrait gives you a fascinating look at the "public vs. private" persona of 19th-century celebrities.

Second, compare this painting side-by-side with Baudry’s The Pearl and the Wave. It’s a totally different vibe—mythological, nude, and much more "academic." Seeing the two together shows you the range of a painter who could do both high-concept fantasy and grounded, soulful portraiture.

Lastly, if you're ever in Paris, hit the Palais Garnier. Look at the ceilings. Then go to the Orsay and look at Madeleine. It’s the best way to understand the dual nature of 19th-century French art—the public spectacle and the private soul.

The real magic of Madeleine Brohan by Paul Baudry is that it doesn't feel like a history lesson. It feels like a meeting. You aren't looking at a dead actress; you're looking at a woman who still has something to say. All you have to do is stop and listen.