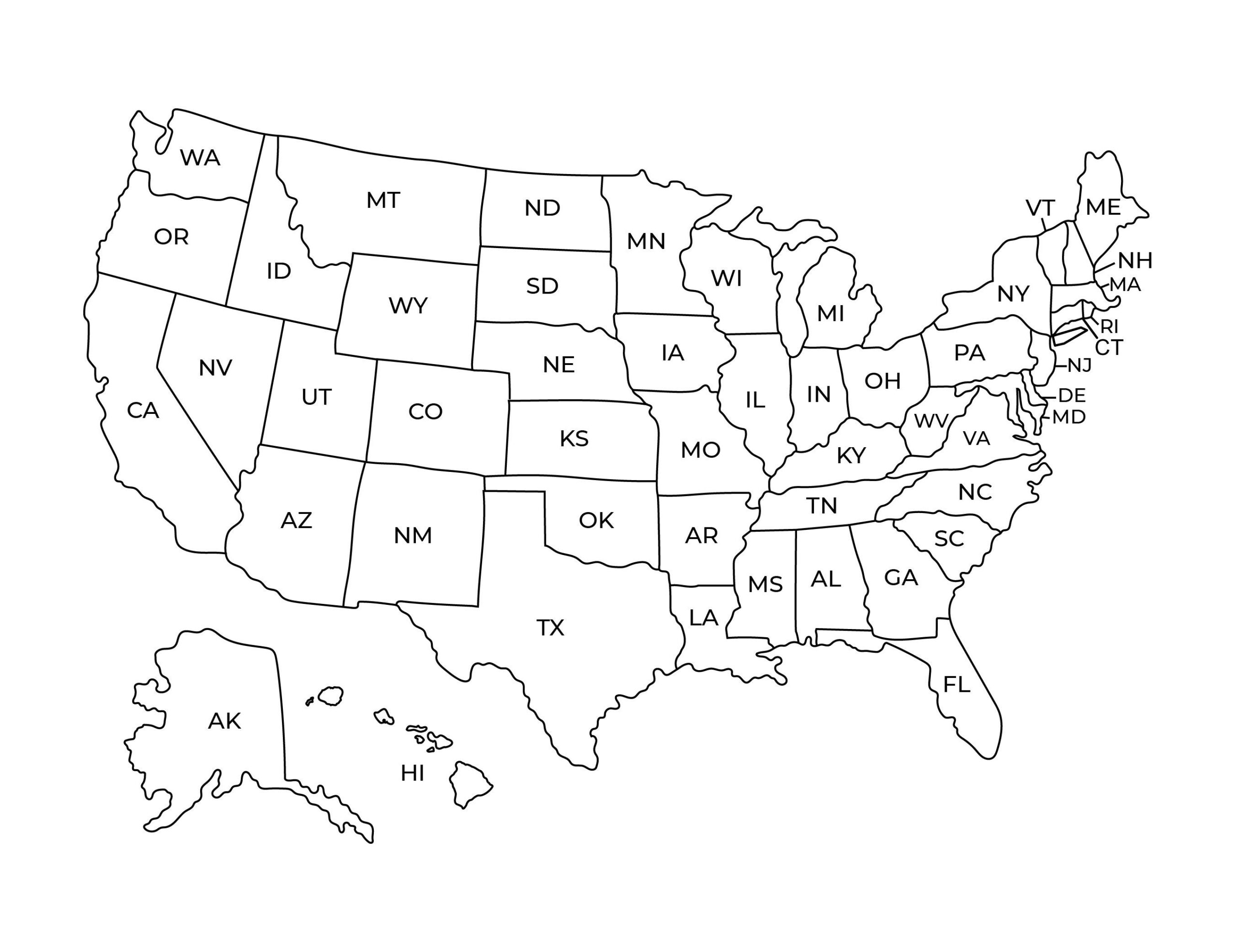

Maps are weird. We look at a US map with states and think we see the whole story of the country, but honestly, what we're looking at is a collection of arguments, accidents, and some really strange geometry. You’ve probably stared at one in a classroom or on a phone screen a thousand times. You see the big, blocky rectangles out West and the jagged, chaotic squiggles of the East Coast. It looks permanent. It feels like it’s always been this way, but every line on that map has a backstory that’s usually way more interesting than the 5th-grade social studies version.

Geography isn't just about where things are. It’s about why.

Take a look at the "Four Corners." It’s that one spot where Arizona, Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico all touch. It’s the only place in the country where you can stand in four states at once. People travel from all over just to put their hands and feet in different jurisdictions. But here’s the thing: because of 19th-century surveying errors, the actual spot isn't exactly where it was legally supposed to be. If we used modern GPS to fix it, the borders would shift. We don't, though. We just keep the map the way it is because changing it would be a legal nightmare. We prefer the "wrong" lines because they're familiar.

The jagged edges vs. the straight lines

When you glance at a US map with states, the first thing you notice is the contrast. The East is messy. The borders follow rivers like the Potomac, the Ohio, and the Mississippi. These are "natural" boundaries, though there’s nothing natural about a legal jurisdiction ending just because a river flows there. The West is a different beast entirely. It’s all grids.

This wasn't an accident. Thomas Jefferson basically obsessed over the idea of a "grid" system. He wanted the land divided into neat, orderly squares. He thought it would make selling property easier and create a more democratic society. Of course, he wasn't really considering the mountains, deserts, or the people already living there. This is why when you fly over Kansas or Nebraska, it looks like a giant quilt.

The Mason-Dixon line is another one. People talk about it like it’s a cultural divide between the North and South, and it is, but it started because two families—the Penns and the Baltimores—couldn't stop fighting over their property lines. They hired Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to trek through the woods and mark the boundary with stones. They were just surveyors doing a job. Now, that line is a massive part of the American psyche.

The tiny details we usually miss

Have you ever noticed the "Kentucky Bend"? If you look at a detailed US map with states, there’s this tiny little nub of Kentucky that is completely detached from the rest of the state. It’s an exclave. To get there from the rest of Kentucky, you actually have to drive through Tennessee or Missouri. It was created because of a double whammy of bad surveying and a series of massive earthquakes in 1811 and 1812—the New Madrid earthquakes—that actually made the Mississippi River flow backward for a bit. It’s a geographical glitch that just stayed there.

Then there's the "Lost State of Franklin." Back in the 1780s, a bunch of settlers in what is now East Tennessee tried to break away and form their own state. They had a constitution and everything. They operated for several years, but they couldn't get the federal government to recognize them. Eventually, the movement collapsed and the land was folded back into North Carolina and later Tennessee. It’s a reminder that the map we see today was never a sure thing. It was a series of "maybes" that eventually stuck.

Why the size of states is so deceptive

The Mercator projection ruins everything. Seriously. Because most flat maps try to represent a curved Earth, the stuff near the poles looks way bigger than it actually is.

👉 See also: Where You Can Actually Shop: Stores to Open on Thanksgiving This Year

Look at Alaska.

On a standard US map with states, Alaska is often tucked into a little box in the corner next to Hawaii. This makes it look manageable. In reality, Alaska is massive. If you plopped it on top of the "lower 48," it would stretch from the coast of Georgia all the way to California. It’s bigger than Texas, California, and Montana combined. But because it's "away" from the mainland, our brains categorize it as a footnote.

Texas gets all the credit for being "the big one," and don't get me wrong, it’s huge. You can drive for 12 hours in a straight line and still be in Texas. But the scale of the West is just fundamentally different from the East. You could fit several New Englands inside a single Western county. This isn't just a fun fact; it changes how politics works, how infrastructure is built, and how people interact with their government. If your "neighbor" is twenty miles away, you have a different worldview than someone who shares a wall with theirs in Brooklyn.

The "51st State" conversation

The map isn't finished. People think it is, but it’s a living document. There are constantly movements to change things. You’ve got the "State of Jefferson" movement in Northern California and Southern Oregon. You’ve got people in Western Maryland who want to split off. And then there's the big one: Puerto Rico and Washington D.C.

D.C. is a weird one geographically. It’s a "district," not a state, which means the people living there have no voting representation in Congress, even though their population is bigger than Vermont or Wyoming. If you look at a US map with states from a hundred years ago, it looks almost the same as today, which is rare in world history. But the pressure is building. Whether it’s through statehood for territories or "Greater Idaho" trying to absorb parts of Eastern Oregon, the lines are always under tension.

How to actually use a map for more than directions

Most of us use maps to get from Point A to Point B. We follow the blue line on Google Maps and don't think about the terrain. But if you want to understand the country, you have to look at the "paper" version—the static version that shows the relationship between the land and the law.

- Check the watersheds. Instead of looking at state lines, look at where the water flows. The Continental Divide is the real "border" of the West. Everything on one side goes to the Atlantic/Gulf; everything on the other goes to the Pacific.

- Look for the gaps. Notice how much empty space there is in the Mountain West versus the urban corridors of the Northeast. That "emptiness" is usually federal land—National Forests or BLM land. It’s land that belongs to everyone, yet no one lives there.

- Find the enclaves. Search for places like Point Roberts, Washington. It’s a piece of the U.S. that you can only get to by driving through Canada. These little anomalies tell the best stories about how the borders were negotiated (or bungled).

The US map with states is basically a record of every compromise the country has ever made. It’s a messy, beautiful, slightly broken representation of how we’ve tried to organize ourselves. It’s not just a drawing; it’s a legal contract that we all live inside of every day.

To get a better handle on this, start by looking at a topographical map instead of a political one. When you see the mountains and valleys underneath the state lines, you start to see why some borders are straight and some are jagged. It makes the "puzzle" of the United States make a whole lot more sense. You'll realize pretty quickly that the land usually wins out over the lines we try to draw on top of it.